Theme Essay for John Michael Bell

Surprise! Plots Don’t Drive the Best Film Adaptations

I remember exactly how I felt when I tore through The Giver in one fevered day. I was twelve. It was the summer of 1999, and for the first time, I physically couldn’t put a book down. Lois Lowry's 1993 novel filled me with thrilling anxiety. It didn’t rely on plot twists and action; instead, it generated tension by having its twelve-year-old protagonist Jonas slowly realize the dark secrets of the world he lived in.

The Giver is the first of a four-part series that predates blockbusters like The Hunger Games (the final book in Lowry’s “Giver Quartet,” Son, was published in 2012). In a seemingly perfect world, in which everyone gets daily injections to dull them, Jonas is given his “life assignment” from the Elders. But his assignment as Receiver of Memories differs from those of his friends, who do caretaking or other communal tasks. It leads him to an old man known only as the Giver, who reveals what’s been lost in their conformist society.

Lowry, the mother of dystopian young adult epics, crafts a realm of emotionless gray and normalizes it. After all, it's all Jonas has ever known. When he sees color for the first time, it's revolutionary:

Jonas listened, trying hard to comprehend. ‘And the sled?’ he said. ‘It had that same thing: the color red. But it didn't change, Giver. It just was.’

‘Because it's a memory from the time when color was.’

‘It was so—oh, I wish language were more precise! The red was so beautiful!’

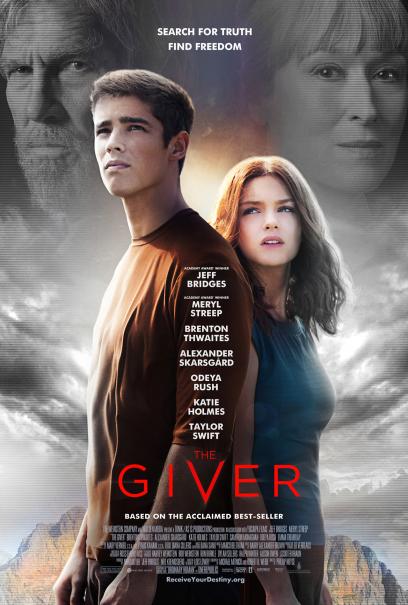

Compared with passages like this, last year's film adaptation of The Giver by veteran director Phillip Noyce is a huge disappointment. Jonas (Brenton Thwaites) explains his life with endless narration such as, “I don't have a last name. None of us did. That day, the day before graduation, I admit it, I was scared. Tomorrow we'd be assigned our jobs….” There is no dramatic tension or energy where there needs to be. When Jonas sees colors, it's another step in a predictable, neutered plot, not the system shock it is in the book. And the ending falls apart completely: Where Lowry closes with sobering and poetic ambiguity, the film reaches desperately for a happy and maddeningly unbelievable resolution.

This is the most boring sort of film: not ineptly made, just relentlessly without vision. Even Meryl Streep, as Chief Elder, has little to do but grimace and speak in a grave monotone. Jeff Bridges’s performance as the Giver is the best in the film; he injects his character with a knowing weariness simply with glances and the tone of his voice. On the other hand, a cameo by Taylor Swift as another Receiver of Memories is just distracting. It's a common pratfall for A-list celebrity cameos—the famous face upstages the actual role—and in a way, it’s a metaphor for the whole film.

This is the most boring sort of film: not ineptly made, just relentlessly without vision. Even Meryl Streep, as Chief Elder, has little to do but grimace and speak in a grave monotone. Jeff Bridges’s performance as the Giver is the best in the film; he injects his character with a knowing weariness simply with glances and the tone of his voice. On the other hand, a cameo by Taylor Swift as another Receiver of Memories is just distracting. It's a common pratfall for A-list celebrity cameos—the famous face upstages the actual role—and in a way, it’s a metaphor for the whole film.

Well, what did I expect, right? Noyce’s The Giver could be seen as yet another example of the movie always falling short of the book. Except I reject that notion altogether. Film adaptations often equal or surpass their source material. There’s nothing about Lowry's YA novels that precludes a terrific film. However, that adaptation would have to explore this material with her depth and nuance. Ironically, in adapting a cautionary tale about the importance of unique cultures and identities, Noyce stripped it of any voice of its own.

The Giver was one of the most essential books of my adolescence. I’d even say that the books I loved when I was grappling with growing up have a borderline spiritual significance for me. Good young adult literature has an intoxicating effect on its audience, but not because teens are easily satisfied or awed. The best YA novels take fully realized, relatable protagonists and place them in vividly rendered settings. While the conventional wisdom says page-turning plots drive the current YA trend, here’s what many film directors don’t understand: the plots of YA books are secondary, a reason to see more locations and meet more characters. The reason for the visit to the world matters less than the visit itself.

Film adaptations of YA novels like The Giver and those from The Chronicles of Narnia series put the plot first, and in doing so, they lose the zest that makes the books so gripping. Consider the titan of young adult novel/film combos: Harry Potter. With the Harry Potter books, I think of the seasons and how richly J.K. Rowling renders them. Each book follows the course of a school year, and changes in season coincide with the plot. I think of Harry the young orphan’s restless summers, spent sequestered in his room with his awful “Muggle” family, awaiting his return to Hogwarts. I think of crisp autumns in magical villages, where Harry and his wizard friends drink butterbeer amid falling leaves and burgeoning dramas. The cold of winter sequesters the stories indoors, parallel to the rising tensions of the books' numerous plots.

In contrast, the eight Harry Potter films start out attempting to capture that same magic, then give up and just recite the plot. The first two films by director Chris Columbus—Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone (2001) and Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (2002)—were criticized for being loyal to the source material to a fault, leading to long and bloated movies. In retrospect, there's a charm to them the later films lack. Harry Potter's lasting appeal isn't the war against Voldemort; it's getting lost in a cavernous maze of school hallways where something never seen before might wait around each turn.

Columbus didn't have a distinct voice of his own, but he brought the sights and sounds of Rowling's books to life. The third and fourth films—Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (2004) and Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (2005), directed by Alfonso Cuarón and Mike Newell, respectively—were more widely praised, and rightly so. Their directors had a blast in this stomping ground for the imagination, and both films have a goofy giddiness to them.

The climax of The Prisoner of Azkaban, for example, is an extended scene in which the main characters gather in a spooky house and learn the answers to every question the book has raised, including the secret role of a rat-like villain. In the movie version, Cuarón speeds this up, turning it into an overwhelming barrage of character revelations that conveys the narrative chaos. And Newell's film, more than any other, makes Hogwarts feel like a real British boarding school instead of a theme park.

But once David Yates took over for the fifth film, Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix (2007), the movies stopped wandering and got down to business in emphasizing the plot. Yes, the fifth book permanently takes the series in a darker direction, but in their vastness, Rowling never stops exploring the nooks and crannies of Hogwarts and the wizarding world. They never lose their sense of wonder. The films, leaner and plot-driven, do.

It’s possible for a film to find its own voice without the book leading the way. Take this moment in Catching Fire (2013), the second Hunger Games film: protagonist Katniss Everdeen (Jennifer Lawrence) is in an elevator with her sometime-love-interest Peeta (Josh Hutcherson) and their mentor Haymitch (Woody Harrelson). Another competitor, Johanna Mason (Jena Malone), enters the elevator and proceeds, rather inexplicably, to strip nude. In the book, the scene does little more than establish Johanna's unpredictability. In the film, director Francis Lawrence (no relation to Jennifer) wisely focuses on Katniss's face. She turns to the side, her jaw jutting in an expression of profound discomfort and annoyance. Jennifer Lawrence gives Katniss an honest and human reaction to an uncomfortable situation, turning what might have otherwise been a gratuitous scene into one of terrific comedy.

It’s possible for a film to find its own voice without the book leading the way. Take this moment in Catching Fire (2013), the second Hunger Games film: protagonist Katniss Everdeen (Jennifer Lawrence) is in an elevator with her sometime-love-interest Peeta (Josh Hutcherson) and their mentor Haymitch (Woody Harrelson). Another competitor, Johanna Mason (Jena Malone), enters the elevator and proceeds, rather inexplicably, to strip nude. In the book, the scene does little more than establish Johanna's unpredictability. In the film, director Francis Lawrence (no relation to Jennifer) wisely focuses on Katniss's face. She turns to the side, her jaw jutting in an expression of profound discomfort and annoyance. Jennifer Lawrence gives Katniss an honest and human reaction to an uncomfortable situation, turning what might have otherwise been a gratuitous scene into one of terrific comedy.

Catching Fire is among the handful of young adult adaptations that match or even exceed their source material. Suzanne Collins's Hunger Games books are praised far more for their plotting than their awkward prose and clumsy characterizations. She relies heavily on blatant metaphors and forced, unnecessary love triangles. The films, meanwhile, unlock the dystopian world of Panem for viewers.

Another favorite YA adaptation of mine is the 2003 film Holes, directed by Andrew Davis and based on the 1998 novel by Louis Sachar (who also wrote the screenplay). Davis and Sachar beautifully capture the book's sunny absurdity and sense of humor.

If only the film version of The Giver had included such humor, spontaneity, or trust in the world its original author created. Instead, it shoehorns Streep's arch-villain character into the plot. In Lowry's book, when the Giver speaks of love for the first time, he does so as if he’s the last speaker of a dying language. In the movie, when Bridges confronts Streep with this concept, he's only talking back to one arbitrary dictator, not defying an entire society.

Lowry's characters aren't just pawns of the plot. They grapple with complex feelings and conflicts, just as I did as an adolescent. They live in their world. When I was twelve, for one unforgettable day, I lived there, too.

Publishing Information

- The Giver by Lois Lowry (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1993).

- The Giver (2014), movie listing on IMDb.

John Michael Bell is a contributing writer for TW and a freelance writer from New Bedford, Massachusetts. In addition to his previous articles for Talking Writing, he has been published in Salon. You can read more of his film criticism on his blog The Sixth Station.

John Michael Bell is a contributing writer for TW and a freelance writer from New Bedford, Massachusetts. In addition to his previous articles for Talking Writing, he has been published in Salon. You can read more of his film criticism on his blog The Sixth Station.