TW Review by John Michael Bell

But, Soft! What Mess in Yonder Window Breaks?

Shakespeare nuts have been dreading this day. Julian Fellowes has gone and broken one of the most sacred rules of adapting the Bard for the big screen: If you want to keep the play’s title, you cannot change the words. Cutting scenes? Fine. Changing the setting? Acceptable, as long as you don’t change the story. But modernizing “Wherefore art thou, Romeo?” No.

In fact, Fellowes’s changes in the 2013 film Romeo and Juliet, released last week, are subtle. He retains virtually all the play’s most famous lines and leaves the main plot untouched. His dialogue alterations come in small scenes between the balcony and the tragic mix-up at the end.

In fact, Fellowes’s changes in the 2013 film Romeo and Juliet, released last week, are subtle. He retains virtually all the play’s most famous lines and leaves the main plot untouched. His dialogue alterations come in small scenes between the balcony and the tragic mix-up at the end.

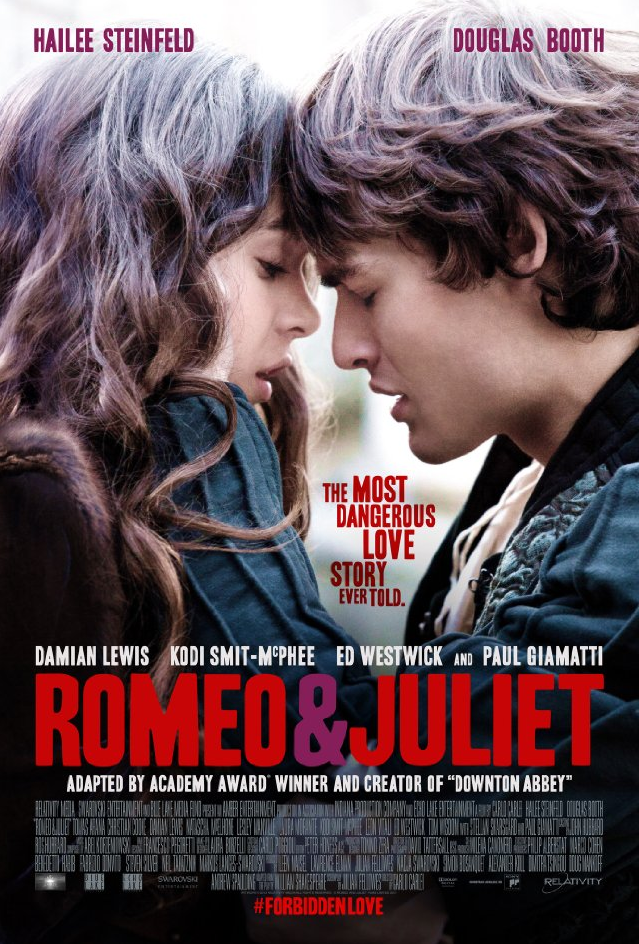

Some even work. In this version, Juliet (Hailee Steinfeld) and her nurse (Lesley Manville) have a relationship that’s warmer and more familial than in most previous depictions. Their dialogue, no longer in iambic pentameter, sounds appropriately conversational. Fellowes, of Downton Abbey and Gosford Park fame, excels at writing interactions in period settings between servants and their employers, mining their dynamics for drama in just a few exchanged words.

I appreciated the brief moments in the new film that sparkled, such as the scene where the Nurse informs Juliet that Romeo has agreed to marry her. Shakespeare’s original runs like so:

NURSE: …Hie you to church; I must another way,

To fetch a ladder, by the which your love

Must climb a bird’s nest soon, when it is dark:

I am the drudge, and toil in your delight;

But you shall bear the burden soon at night.

Go, I’ll to dinner; hie you to the cell.JULIET: Hie to high fortune!—honest nurse, farewell.

In Fellowes’s screenplay, this becomes enjoyably jittery, maternal dialogue—the Nurse asks Juliet to wait until “after you’ve had a bath,” for instance. Her instructions to Juliet about meeting with Friar Laurence (Paul Giamatti) to marry Romeo in secret are stripped of the play’s old-fashioned flourish. The more natural-sounding dialogue amplifies Manville’s performance.

Unfortunately, such naturalness never extends to the title characters. This Romeo and Juliet has already been roundly panned in reviews for its leaden approach to adapting a story so overdone that it only works if it sings. Julian Fellowes rewriting Shakespeare should have yielded bold results. Yet, this lifeless film would have failed even if he and director Carlo Carlei had followed the Bard’s words to the letter.

And that’s a shame. Changing Shakespearian dialogue for new audiences makes sense, and if Fellowes had taken advantage of the creative freedom he gave himself, he might have explored the characters in ways other filmmakers have not dared.

Movie productions of Romeo and Juliet have often been dogged by controversy. Franco Zeffirelli’s 1968 version included nudity. Baz Luhrmann’s 1996 version (Romeo + Juliet) offended many critics with its violence and kinetic, MTV-inspired visuals. Swordfights became shootouts; Verona turned into Verona Beach; and Romeo attended the masquerade ball high on ecstasy.

It’s also true that many who have adapted Shakespeare’s stories on stage and screen have used different dialogue and settings. They just change the titles. Akira Kurosawa turned Macbeth and King Lear into Throne of Blood and Ran, for example, altering the stories slightly and setting them in feudal Japan.

Regardless of dramatic alterations, films such as these accurately convey the Bard’s intent. West Side Story, despite a shift to mid-twentieth-century Manhattan and those Jets and Sharks, follows Shakespeare’s story beat for beat. Even contemporary teen comedies can remain true to the underlying story: Ten Things I Hate About You is a pretty straightforward, and quite funny, adaptation of The Taming of the Shrew.

The point is, great films have been made both by adapting Shakespeare’s plays faithfully and by lifting the stories with new words. Complaints about Carlei and Fellowes disrespecting Shakespeare through dialogue changes are therefore overblown, even ludicrous. I didn’t give a damn when throwaway conversations between Romeo and Mercutio were presented in Fellowes-style banter. I did care tremendously, however, when line after line from the original play was delivered with all the force of a hung-over cold reading.

There’s much blame to go around here, but some must fall on the film’s leads. Steinfeld's performance in the recent remake of True Grit was a wonder to behold. There, she was confident, taking the colorful dialogue of Charles Portis by way of the Coen Brothers and owning it. Here, she practically mumbles many of her lines, trying to act through meaningful stares. When she bids farewell to Romeo before he heads into exile, she seems more passively perplexed than heartbroken.

Douglas Booth as Romeo suffers from the same lack of zest. Romeo is not a sensible character, and previous Romeos (Leonard Whiting in 1968, Leonardo DiCaprio in 1996) have tapped into this, delivering performances rife with zeal and hyperbole.

When Booth talks of love, he lacks the capital letters and exclamation points that made Whiting and DiCaprio so memorable. Compared with those two, he sounds downright sarcastic. Even if he’s attempting quiet resignation with his reading of “I am fortune’s fool,” Booth achieves something closer to a sneer.

Good adaptations of Romeo and Juliet don’t just go through the motions. Zeffirelli’s version works because its lead actors throw themselves into their roles with abandon. The balcony scene between Whiting as Romeo and Olivia Hussey as Juliet is a sustained burst of joy, so delightfully played that we forgive the characters promising undying love after knowing one another for only a few hours. Cinema and drama alike can transcend logic by tugging heartstrings.

In the new film, the balcony scene is as flat and stagey as a high school production. The actors recite their lines and kiss. It’s not just the fault of the actors, but of a director who infuses the scene with absolutely no visual character. For me, the barrage of closeups of Steinfeld and Booth’s faces quickly grew tiresome, then maddening, then disheartening.

Ironically, some of the weaker aspects of the film arise not from its changes to Shakespeare’s original but in Carlei and Fellowes’s attempts to adhere to it. Zeffirelli excised the scene where Romeo visits the apothecary to acquire poison. It is a grim scene, clinical in Romeo’s commitment to his own death. It’s also not essential to the story, which is why Zeffirelli’s film works without it.

Ironically, some of the weaker aspects of the film arise not from its changes to Shakespeare’s original but in Carlei and Fellowes’s attempts to adhere to it. Zeffirelli excised the scene where Romeo visits the apothecary to acquire poison. It is a grim scene, clinical in Romeo’s commitment to his own death. It’s also not essential to the story, which is why Zeffirelli’s film works without it.

The scene is included in the new Romeo and Juliet, and functions…well, as a means to show Romeo getting his poison. Done right, this scene can help steer the tone of the story’s ending. Here, it’s just one of many things done rote.

Carlei and Fellowes include another scene that both Zeffirelli and Luhrmann cut from their films: Juliet’s grieving fiancée, Count Paris, sees Romeo approaching her tomb and challenges him to a duel. They fight, and Romeo kills him. In this film, it’s unpleasant and unnecessary; it interrupts the momentum of the ending, injecting it with needless killing that has no sense of weight or the tragedy behind it.

Different adaptations of the same source material can be exciting. It’s why we still perform and watch Shakespeare today, and Romeo and Juliet occupies a particular place in our hearts and minds. We know how it ends. If we want to be cynical, we can dismiss the entire thing as the foibles of two stupid teenagers who can’t tell a first crush from a love worth dying for. But done right, the play is a testament to the power of drama to appeal to broad, earnest emotions.

Those big emotions make it irresistible to filmmakers and writers—and endlessly challenging for those who keep trying to convey the beautiful foolishness of young love. Romeo and Juliet, silly as they are, are impossible to forget. Their story has moved me against my better judgment time and again. Played well, their proclamations of love are some of the most romantic lines an actor can deliver. Never should they be upstaged by the Nurse.

Art Information

- Movie stills are from Romeo and Juliet, courtesy of Relativity Media.

John Michael Bell is a contributing writer and social media assistant for Talking Writing as well as as a freelance writer in New Bedford, Massachusetts.

John Michael Bell is a contributing writer and social media assistant for Talking Writing as well as as a freelance writer in New Bedford, Massachusetts.

His love of pop culture, along with his need to make sense of it through writing, often drives him to the brink of insanity, which he resolves by making a pilgrimage to the Brattle Theater in Harvard Square.

See more of JM's writing at his blog The Sixth Station.