Feature by John Michael Bell

Virtual Literature: When the Story Happens to You

There’s a splendid moment near the beginning of BioShock Infinite. Soon after I click “Play Game” in the opening menu, my character is in a temple for an unknown religion. It’s gorgeously rendered, with torch-lit marble statues and hymns being sung. Cloaked worshipers walk in line, as if hypnotized, through streams of water running across the temple’s floors. It’s a beautiful place, but mysterious—and I want to see more. Yet, I can do it at my own pace, exploring the scene for as long as I want.

This, I think, is something only video games can do.

BioShock Infinite, developed by Irrational Games and released in 2013 by 2K, is far from perfect. Its story soon becomes muddled as the game descends into repetitive combat against wave after wave of robots and racist gunmen. Still, with sales of more than four million copies, its audience surpasses that of any 2013 novel. More to the literary point, many major video-game titles now feature fully developed fictional worlds with characters brought to life by voice actors.

If players of the BioShock games (Infinite is the third in the series) are lured by the graphics and action, they’re also hooked by the question posed by any good tale: What happens next? But there’s another twist as well: What should I do next? BioShock Infinite is a first-person shooter, meaning the world is shown from the player’s perspective, as if it’s through his or her eyes. You don’t control a character on the screen—you are the character.

A decade ago, film critic Roger Ebert famously said this interactive aspect of games prevented them from being art. Indeed, first-person shooters that constantly put you in the line of fire may seem at odds with losing yourself in a novel. But in surprising ways, even violent games like BioShock Infinite or Halo allow immersion in the story much as page-turning thrillers or romance novels do.

In 2014, the best narrative games challenge Ebert’s claim that “serious film and literature” demand “authorial control.” Narrative video games run the gamut from first-person shooters to role-playing games that involve more than blasting another alien to very un-video-game-like stories such as Gone Home. Just as novels were once a new a form of storytelling that included a character’s inner life, narrative games have transformed author-controlled plots with player interaction.

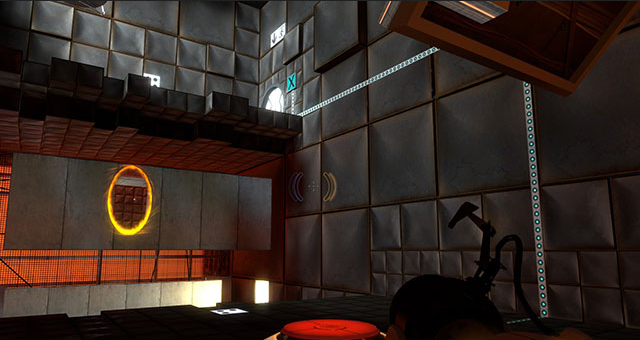

Consider Portal, a 2007 game developed by Valve. Its antagonist is a murderous artificial intelligence named GLaDOS, and for most of the game, she’s nothing more than a computerized voice. As played by voice actor Ellen McLain, at first GLaDOS seems innocuous, leading you through a series of puzzles and promising “cake” as a reward. But that all changes the moment she tries to lead you into an incinerator. When you thwart her plans to burn you alive, she desperately keeps up the ruse:

We are pleased that you made it through the final challenge where we pretended we were going to murder you. We are very, very happy for your success. We are throwing a party in honor of your tremendous success. Place the device on the ground, then lie on your stomach with your arms at your sides. A party associate will arrive shortly to collect you for your party.

GLaDOS is one of the funniest villains I've encountered in recent years. And as I progressed through the game’s puzzles while listening to her banter, it was impossible not to get attached to her. She’s a real character—the kind that video games excel at bringing to life.

“Interactivity cannot just be dismissed,” Janet Murray told me in a recent email interview. “It is the essence of the medium.” Murray, a literature professor at Georgia Tech, has been championing digital narratives for decades. In many ways, Portal and a host of other recent games have finally caught up with what she was talking about in her 1997 book Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace:

[W]e rely on works of fiction, in any medium, to help us understand the world and what it means to be human. Eventually all successful storytelling technologies become ‘transparent’: we lose consciousness of the medium and see neither print nor film but only the power of the story itself.

Murray’s vision of “expressive” digital art is no longer futuristic. GLaDOS may be a disembodied voice, but she’s a wonderful antagonist. The player’s interaction with her is what builds the story—and such interactivity is precisely what leads to great moments of video-game art.

From Mario to Mass Effect

Nintendo’s Super Mario Bros. turns 29 this year, and it’s as fun to play now as it was in 1985. But in the last three decades, video games have evolved far beyond the simple pleasures of a plumber stomping sentient fungi.

These days, dedicated gamers don’t treat a game like mere software, with a list of pros and cons that determine its “grade.” BioShock Infinite set the gaming blogosphere aflame with critiques of its depictions of early twentieth-century racism (it’s set in an alternate 1912), among other hot topics. Geek culture has long been fertile territory for fierce debate, but that debate can now sound like a creative writing workshop. Here’s the blogger Azuriel on the game’s use of multiple timelines:

BioShock Infinite is a game in which all your actions are voided. Everything you struggled to accomplish is erased. None of it happened. Every moral choice you made, every time you refrained from stealing from cash registers, every interracial kindness you demonstrated, never matters because those people/scenarios never exist. It boils down to a 'it was all a dream' scenario.

Negating a player’s narrative is one of the easiest ways to rile gamers. We expect to control the storytelling in such branching narratives. As Murray told me, “One of the most important features of video games is the ability to replay the same scenario with different choices or different parameters.”

In Hamlet on the Holodeck, she cites the 1993 megahit Myst as a breakthrough with its four distinct endings: You could free one of three characters (two evil brothers named Achenar and Sirrus or their innocent father Atrus) from magical imprisonment or none of them.

By 1995, Chrono Trigger, a role-playing game (RPG) involving many time-traveling characters and a vast fantasy setting, featured more than a dozen endings. Its narrative was more complex than Myst’s, with an ending determined by player choices throughout the game as opposed to a single, clear-cut choice at the very end. Two people playing Chrono Trigger could experience two very different narratives.

But another major aspect of Myst’s appeal—its first-person perspective—was also a part of early combat-driven games like Doom. In Myst, you wandered a photo-realistic world alone, solving puzzles. In Doom, you wandered a series of maze-like levels, gunning down demons. The narrative scope of each was limited. When Valve released Half-Life in 1998, it melded the principles of both into a thrilling first-person story about a scientist running for his life from alien invaders and the soldiers sent to wipe them out. Solving puzzles and shooting aliens were part of the experience, but Valve’s developers used them to tell a larger overall story that made for a better game.

In Mass Effect, BioWare’s recent science fiction RPG trilogy (launched in 2007 and concluded in 2012), different players can experience wildly different stories from beginning to end. In the first game, for instance, one of your in-game allies, a reptilian alien warrior named Wrex, grows angry with you. You can talk sense into him, allowing Wrex to continue as a major character in the next two games—or you can kill him, wiping a significant figure from the game’s universe. If Myst conveyed the possibilities of multiple endings and Chrono Trigger showed how those endings could expand the whole narrative, Mass Effect lets players travel through an epic adventure that is all their own.

“A movie or a book typically tells a third-person story,” notes Ethan Gilsdorf, who regularly writes about geek culture and is the author of the 2009 book, Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks. Even when the story is told in the first-person, he added in an email exchange with me, “we are hearing about another person's life or experience. Video games make the player the protagonist in a way that a reader or film viewer never quite can be.”

In Search of Gaming’s Breaking Bad

Despite the popularity of Halo and BioShock, there’s still no gaming equivalent of The Sopranos and Breaking Bad. Television drama, once considered a second-rate storytelling medium, now draws serious writers who want to create TV “novels.” While I believe Portal merits as much adulation as Breaking Bad, gaming has yet to attract many literary auteurs or the same critical acclaim.

Except for Gone Home. Published last summer by indie developer the Fullbright Company, it’s earned more comparisons to literature than any video game in recent memory. “It might be best to think of Gone Home as a novel,” writes Daniel Nye Griffiths in his review of the game for Forbes. New York Times critic Chris Suellentrop calls it “gripping fiction.”

Fullbright’s website describes it as “a story exploration video game,” which is more accurate. You play as Kaitlin Greenbriar, a young woman returning to her family’s home after a year studying abroad. The house is empty. There’s a cryptic note from her teenage sister on the door. You spend the whole game figuring out what happened. Where did everyone go?

Gone Home has no enemies to fight, no platforms to jump on, no puzzles to solve. The game is set in 1995, before the digital age kicked into gear. The house is littered with mementos and notes—old-fashioned clues that now would exist only as email, texts, or tweets—but in the game, they help Kaitlin reconstruct where her family has gone.

As in Portal, the character who emerges as the star of Gone Home is not the protagonist. It’s Kaitlin’s seventeen-year-old sister Sam, whose story is told entirely through a series of voiceovers by voice actor Sarah Grayson. The voiceovers take the form of diary entries addressed to Kaitlin. They’re triggered when you (as Kaitlin) interact with certain objects throughout the game. When you pick up a can of red hair dye, Sam describes an encounter she had with Lonnie, a girl she has a crush on:

Lonnie brought her hair dye over today. She said, ‘I need to fix these roots—think you could help?’

Dying hair is weirdly intimate. I don’t know if I’ve touched someone else’s scalp before. That’s pretty intimate, right? It felt intimate.

We looked into the mirror together after, and I expected her to say something about how it looked crappy, or good, or whatever. But that’s when she said, ‘You’re so beautiful.’ And she was looking at me!

Right in that moment, I wanted to say…something. But I waited. And the moment was gone.

Sam’s voice is vulnerable and deeply human. Moments like this one are eloquent in their awkwardness, especially because Grayson’s performance is so marvelous.

The method of telling a story through audio clips is not new to Gone Home. Steve Gaynor, the game’s lead designer and cofounder of the Fullbright Company, worked previously on BioShock 2. In the BioShock franchise, players regularly encounter audio diaries they can listen to without having to pause the gameplay. The diaries flesh out the game’s story without interrupting the action.

“Audio diaries are such an essential part of the BioShock games,” Gaynor told me in a phone interview. “It’s one of the first tools we had…. Having Sam’s voice be the human element in [Gone Home] was important experientially, for Sam to be able to have a say and tell her story in her own words.”

Her narration has reminded many critics of a character in a novel. But in a novel, the author would be controlling how Sam’s story is told and the pace at which information is revealed. In Gone Home, players unlock Sam’s story for themselves.

Literature that Isn’t Literature

Now, when I play a new game, I reflexively analyze it as a work of storytelling, not just as a fun experience. I ache a little bit when a new game doesn’t show narrative ambition. Even if I’m disappointed in BioShock Infinite, simply debating its narrative potential is a huge step forward in a cultural conversation that has tended to relegate video games to amusement park thrills.

In fact, it no longer makes sense to compare narrative games with films and novels. They’re not novels in any traditional sense, and that’s a good thing. In an email exchange with me, Ian Bogost, author of several books about video-game theory and Janet Murray’s colleague at Georgia Tech, had this to say:

The best narrative games I've played recently aren't trying to be genre fiction—if anything, they try to trouble the idea of narrative itself. This is how games have to handle storytelling—by admitting that the twentieth century happened to narrative, rather than burying their heads in the Victorian novel.

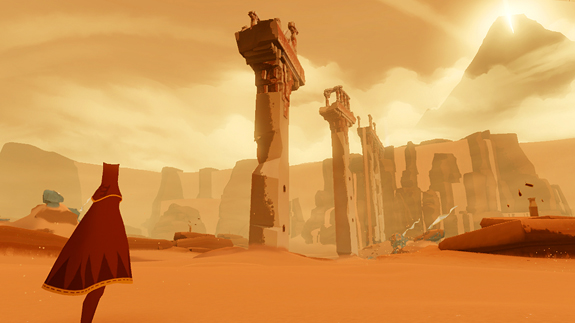

Some games don’t need a plot to tell a good story. Consider the 2012 game Journey, developed by Thatgamecompany and published by Sony for the PlayStation 3. You play online alongside a stranger, with whom you can only communicate through musical notes. You work together to cross challenging terrain and, eventually, scale a mountain. Your mutual effort becomes the story. At the end, the screen names of the people you played with are revealed—and it’s a poignant moment. It’s not the classic narrative arc, but Journey moved me tremendously.

Obviously, video games aren’t books. What’s less obvious, especially to fans of literary storytelling, is that video games are as captivating as good literature when they’re not trying to be literature. Games rev us up, make us laugh, even make us cry. But we aren’t being told a story. The story is happening to us, and this interactivity is what allows the best games to be as absorbing as good fiction.

There’s a moment in Gone Home I’ll never forget. I’m rummaging through the attic when I find a note to Sam from Lonnie. The note is a brief, heartfelt declaration of love and great sadness. It feels real, as if I’ve stumbled into a private exchange. The note isn’t part of a plot twist; it just adds that much more dimension and color to Sam’s world. And my heart breaks a little for these characters. I stand up from my computer and take a deep breath. I’m surprised to find tears in my eyes.

This, I think, is something only video games can do.

Publishing Information

- “BioShock Infinite Ships 4 Million Copies” by Eddie Makuch, Gamespot, July 30, 2013.

- “Why Did the Chicken Cross the Genders?” by Roger Ebert on his website, November 27, 2005.

- Hamlet on the Holodeck by Janet H. Murray (Free Press, 1997).

- “BioShock Infinite and Fictional Racism,” How Many Princesses, July 7, 2013.

- “On BioShock Infinite, Racism, and American Exceptionalism,” MbraceNterpret, May 5, 2013.

- “My Issues with the BioShock Infinite Plot” by Azuriel, In an Age, April 4, 2013.

- “Gone Home Review—A Teenaged Girl at the Heart of a Grown-up Game” by Daniel Nye Griffiths, Forbes, August 15, 2013.

- “A Student’s Trip Ends; a Mystery Just Begins” by Chris Suellentrop, New York Times, August 18, 2013.

- “Perpetual Adolescence: The Fullbright Company’s Gone Home” by Ian Bogost, Los Angeles Review of Books, September 28, 2013.

Art Information

- BioShock Infinite press image distributed by Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc.

- Portal press image distributed by Valve.

- Mass Effect 3 press image distributed by BioWare.

- Gone Home press image distributed by the Fullbright Company.

- Journey press image distributed by Thatgamecompany.

John Michael Bell is a contributing writer for Talking Writing and a freelance writer from New Bedford, Massachusetts. When he’s not busy talking your ear off about Hayao Miyazaki movies, you can probably find him playing through the Mass Effect games again.

John Michael Bell is a contributing writer for Talking Writing and a freelance writer from New Bedford, Massachusetts. When he’s not busy talking your ear off about Hayao Miyazaki movies, you can probably find him playing through the Mass Effect games again.

For more of his thoughts on film and pop culture, see his blog The Sixth Station.