Essay by Lorraine Berry

Students Grapple With Columbine and Newtown

This January, a few weeks after the Sandy Hook Elementary School shootings, I reread Columbine by journalist Dave Cullen, the book I’d assigned in two of my courses. I’d read it when it first came out in 2009, but now I studied it with teacher eyes.

This January, a few weeks after the Sandy Hook Elementary School shootings, I reread Columbine by journalist Dave Cullen, the book I’d assigned in two of my courses. I’d read it when it first came out in 2009, but now I studied it with teacher eyes.

Somewhere in Section IV, in which Cullen delves deep into the thoughts that drove the killers, a wave of nausea moved through me. It started in my midsection, then spread to my scalp and the ends of my fingers and toes. I couldn’t read one more word about the suffering at Columbine High School in that awful spring of 1999.

I shut the book and leaned back in my seat, taking deep breaths until the feeling passed.

A month later, I joined a group of professors and the Dean of the School of Education at SUNY Cortland in organizing a teach-in about guns in schools. We’d booked it for a room that held 195 seats and ended up with close to 300 people.

We weren’t surprised by the students’ fear, but we were stunned by the number who showed up to defend the rights of anybody to carry a gun anywhere, including a classroom, if that’s what it takes to make school kids safe.

Someone brought up mental health screening and how that would have prevented the shootings at Sandy Hook. At that point, I couldn’t resist mentioning Columbine.

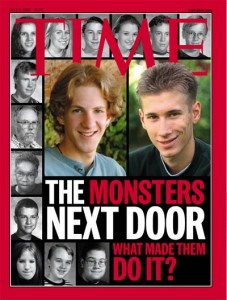

I told the standing-room-only crowd that one of the teen shooters, Eric Harris, was a psychopath—so good at acting normal that he’d even fooled the psychiatrist who’d released him from a juvenile delinquent counseling program. But the other, Dylan Klebold, had been depressed, not psychopathic. Suicidally depressed, full of rage turned inward—but crazy? No.

My assertion met with protests: If Dylan wasn’t crazy, why would he do that?

I mentioned the social psychology experiments conducted by Stanley Milgram in the 1960s, which showed how good people could be convinced to do bad things. I then told the group that if they wanted to gain an understanding of Sandy Hook, they should begin by reading Columbine.

As I watched people write the name of the book and author onto slips of paper, I anticipated the discussions I’d have in the following days with my students. Many of them were education majors (as is a majority of the student body at SUNY Cortland). I knew that what had happened in Newtown would be troubling them.

Talking about Columbine, I told myself, would allow them to use their critical thinking skills to move beyond the myths about what causes awful events such as school killings. As they looked for ways to make sense of these tragedies, they would discover, through this book, that the truth defies easy explanations. They were about to confront the realization that much of life is out of our control.

They were also about to surprise me.

I assumed that Columbine had nothing new to teach me this time around, but my students showed me I was wrong. In hearing their thoughts about the book, I came closer to its truths than I ever had before.

• • •

Each semester, I teach creative nonfiction. I organize all the readings around a theme and have students write their two papers for the course on that theme.

By last October, I’d decided on the theme of “coming of age in time and place” for my current spring course. That’s when I first thought of Columbine. In a terrible and magisterial way, it’s a coming-of-age account of all fifteen people who died that day in a high school in the Denver suburbs, especially the killers.

Since most of my students were born in the early to mid-1990s, I believed it would be good to cover an event that had happened during their lifetimes. I also wanted to expose them to Cullen’s ten years of research, which dismantled so many of the myths that persist about Columbine.

Since most of my students were born in the early to mid-1990s, I believed it would be good to cover an event that had happened during their lifetimes. I also wanted to expose them to Cullen’s ten years of research, which dismantled so many of the myths that persist about Columbine.

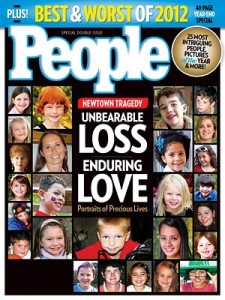

Then I forgot about the book and my spring syllabus—until that horrible day last December in Newtown, Connecticut. Sandy Hook.

Suddenly, I felt prescient. My students would return from the holiday break full of questions and fears about what it means to be a teacher.

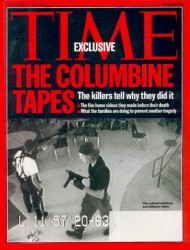

In late December, I decided to assign Columbine in another class as well—my magazine writing course—because it would allow those students to take a current event and put it into a new context. I wanted them to understand, as Cullen acknowledges in his author’s note, that the media got a lot wrong that day. Cullen writes:

To avoid injecting myself into the story, I generally refer to the press in the third person. But in the great media blunders during the initial coverage of this story, where nearly everyone got the central factors wrong, I was among the guilty parties. I hope this book contributes to setting the story right.

• • •

When the spring semester began, I felt ready for anything—except how much students resonated with Cullen’s book. Our discussions often went past our allotted time, leaving the next class waiting in the hall.

Even though my students were in elementary school when Columbine occurred, they started out convinced they knew a lot about it. They trotted out the conventional wisdom: The killers were Goth members of the Trenchcoat Mafia, victims of bullying jocks. They were loners who had struck out at those who tormented them. They wanted justice against those who had made their lives hell.

Contrast their perceptions with Cullen’s description of Eric Harris in Chapter Two:

Dates were not generally a problem. Eric was a brain, but an uncommon subcategory: cool brain. He smoked, he drank, he dated. He got invited to parties…. He broke the rules, tagged himself with the nickname Reb, but did his homework and earned himself a slew of A’s.… And he got chicks.

Prom was Saturday night, and Eric wanted a date, but, as it turned out, it was his geeky friend Dylan “who’d scored the prom date,” Cullen writes. “His tux was rented, the corsage purchased, and five other couples organized to share a limo.” From Eric’s point of view:

How crazy was that? Dylan Klebold was meek, self-conscious, and authentically shy. He could barely speak in front of a stranger, especially a girl…. Eric slathered girls with compliments; Dylan passed them Chips Ahoy cookies in class to let them know he liked them. Dylan’s friends said he had never been on a date; he may never have even asked a girl out—including the one he was taking to prom.

The massacre occurred just three days after the prom, which means that Dylan went to it knowing he planned to kill many of his fellow attendees. So, I asked my students, how did Cullen’s initial portrait of Dylan and Eric square with what they’d been led to believe?

It didn’t.

• • •

In Section I of Columbine, Cullen introduces everyone involved in the events of April 19, 1999. Each profile provides clues about who will encounter the killers that day. Still, Cullen does not speculate, at least in his initial portraits of them, about which of these people will die, escape, lie injured, or aid the killers in ways they couldn’t imagine.

In Section I of Columbine, Cullen introduces everyone involved in the events of April 19, 1999. Each profile provides clues about who will encounter the killers that day. Still, Cullen does not speculate, at least in his initial portraits of them, about which of these people will die, escape, lie injured, or aid the killers in ways they couldn’t imagine.

Many of my students—both in the creative nonfiction course and magazine class—told me they’d resisted the temptation to go on the Internet and look at websites devoted to Columbine. They knew they’d find a list of the victims, along with photographs.

“I care about each of the people that Cullen has written about,” one said in a typical comment, “and I can’t bring myself to find out if they died.”

They were reading the nonfiction book as if it were a novel. Even though they knew the general outlines—21 students injured, 12 students and a teacher dead, plus the killers—they didn’t want to know yet which of these characters would be taken from them.

I still find this remarkable. The Internet is so much a part of my students’ lives that I sometimes feel as if I’m pushing them to read a book. Here, I didn’t have to push.

They were deep into Cullen’s account—and becoming confused. Where was the Trenchcoat Mafia? Where were the bullies? If anything, Cullen had documented that Eric and Dylan bullied other kids, mostly by calling them “fags,” the standard high-school male dis of any guy who doesn’t measure up to someone’s standards of masculinity.

Where were the loners? Dylan and Eric had active social lives—Eric was popular, for crying out loud—and Dylan? Dylan seemed incapable of hurting anyone.

When, at the end of the first section, Cullen begins to describe what happened that day, he makes clear that the boys didn’t have a list; there were no specific targets. The people who got shot just happened to be in the line of fire.

There was no pattern to who had been killed and why.

• • •

Cullen had hooked my classes. They read further into the book, looking for answers as to why this happened. A narrative about two bullied boys who were seeking revenge made sense to them. Two boys who just walked into their school and started shooting up the place? That didn’t make sense at all.

In fact, as Cullen argues persuasively, Columbine was not supposed to be a school shooting at all. Eric had spent almost two years planning a massive bombing. He didn’t want to kill just a dozen or so; he wanted to kill hundreds—to “triple McVeigh’s total.”

It was the failure of the bombs to ignite that led these boys to wander the halls shooting people, mostly in the library, where at last they took their own lives.

Surely, if the killers had been planning this event for two years, my students said, someone must have known they were up to something.

Well, yes. Dylan’s prom date bought guns for the pair, using the gun show loophole and avoiding the background check. The two took friends target shooting with them, but those friends assumed they were just goofing off. A friend’s mother was alarmed by Eric’s behavior, but when she tried to tell the Harrises something seemed wrong, they ignored her.

Well, yes. Dylan’s prom date bought guns for the pair, using the gun show loophole and avoiding the background check. The two took friends target shooting with them, but those friends assumed they were just goofing off. A friend’s mother was alarmed by Eric’s behavior, but when she tried to tell the Harrises something seemed wrong, they ignored her.

The boys were known to the Littleton, Colorado police. The police arrested them for petty theft when they broke into a van and stole some electronics, and they placed the two in a juvenile program to avoid jail time. The police knew that Eric was disturbed—he maintained a website overflowing with hate-filled screeds—but they failed to follow up on the information they had.

My students were outraged. Why hadn’t anyone monitored the boys, if Eric was bragging about the things he wanted to do?

I asked them to think of the logistics of assigning a police officer to monitor Eric’s behavior at all times. I asked whether the public would pay for that.

But what about their friends?

I asked them why kids don’t turn in other kids. Because people will hate you, they responded ruefully. Because turning someone in makes you a narc. And if you insert yourself into a bullying situation, you become a target.

“It’s easy to be brave in the abstract,” I said. “It’s not so easy in reality.”

But certainly the parents must be to blame. Both Dylan and Eric kept journals—jammed with self-loathing and suicidal ruminations (Dylan) and detailed plans for blowing up the school (Eric). Why hadn’t their parents read them?

“Really?” I asked. “You think it’s okay for parents to invade a teenager’s privacy by reading his journal?”

Several students reported that their parents had read their journals. It was one of the reasons that many of them had stopped writing in them. And yet, they insisted, when they were parents, they’d read their children’s journals, too, if they thought their kids were hiding something harmful or scary.

This admission disturbed me. Hadn’t they kept secrets from their parents? Hadn’t we all?

“The thing is,” I said, “I would never have read my own kids’ journals, so in your eyes I would have been just as guilty as the Klebolds and the Harrises.”

My students seemed surprised by my response, almost shocked into silence. I felt uneasy, too, although at that moment I couldn’t pinpoint why.

• • •

Cullen spends a lot of time defining psychopathy. Unlike the mentally ill, who frequently don’t know the difference between right and wrong, psychopaths are rational human beings who just don’t care about the rules of human behavior. Columbine even includes a checklist for determining who is a psychopath beginning in the teenage years:

[G]ratuitous lying, indifference to the pain of others, defiance of authority figures, unresponsiveness to reprimands or threatened punishment, petty theft, persistent aggression, cutting classes and breaking curfew, cruelty to animals, early experimentation with sex, and vandalism and setting fires.

“Eric bragged about nine of the ten hallmarks in his journal” and on his website, Cullen adds. “Only animal cruelty is missing.”

Psychopaths are different from the mentally ill in another crucial way: they’re charmers. They can fool anybody, including psychiatrists. They know what they’re supposed to say; they just don’t believe a word they are saying.

Eric knew he was planning something evil: “I will force myself to believe that everyone is just another monster from Doom,” he wrote. “I have to turn off my feelings.”

Dylan. Well, Dylan is a mystery. And for most of Columbine, he remains a mystery. Students asked again and again: Why did he participate? Cullen floats the theory of the “dyad phenomenon”:

A second, less common approach to the banality of murder seems to be the dyad: murderous pairs who feed off each other. Criminologists have been aware of the dyad phenomenon for decades: Leopold and Loeb, Bonnie and Clyde, the Beltway snipers of 2002…. An angry, erratic depressive and a sadistic psychopath make a combustible pair.

In each class, one student ventured to say what the others were thinking: “The thing that scares me is that if I had been in high school with Dylan, I can see myself being his friend.”

As soon as that dam was breached, a lot of them admitted to the same thing. Dylan seemed so likeable. How could he be a stone cold killer?

How could someone they liked turn out so bad? They were shaken.

• • •

What they knew about Columbine before reading the book all came from media accounts. And it was all wrong.

“I think the media got a lot of things wrong about Sandy Hook, too,” one student ventured, and the others concurred. We discussed how the media incorrectly reported the name of the killer; how reporters, looking for a scoop, shoved microphones in the faces of traumatized elementary school kids. We remembered the reports that a second shooter was on the loose.

Now that the myths about Columbine had been dispelled, my students were left with the unquiet feeling that a horrible thing had happened and the chances to prevent it—if it was preventable—were only apparent in the aftermath. They were rethinking Newtown, too, and what it meant to them personally as prospective teachers, parents, and writers.

My students confessed to being more confused after reading Columbine than they’d been beforehand. Does the blame for Eric’s actions rest with him, or with whatever made him a psychopath? Many argued that, while Dylan was partly to blame for what happened, he was also Eric’s victim—someone who never would have acted on his own.

In Eric’s later journals, he fantasizes about raping and killing women. My students shuddered to think that he might have turned into a serial killer, and a couple of brave souls wondered if maybe, given how sick Eric was, the events at Columbine were a small portion of the havoc he could have wreaked.

I know it scared my students to admit these thoughts. They were in dangerous territory. They worried that saying these things out loud made them terrible people, and they said so—but I was proud of them. Proud and amazed.

When any horrific event occurs, it’s natural to try to put as much distance as possible between ourselves and what happened. With the help of a book—and their critical thinking skills—my students had let themselves look at the events of Columbine up close. They’d gone past the easy answers. They had confronted the inadequacy of blame and the truly scary randomness of evil. And they’d acknowledged their common humanity with both the victims and the killers.

• • •

Going into this teaching experience, I was convinced I’d already learned the lessons of Columbineand Sandy Hook: that much in life is out of our control, that we need to nonetheless let go of our fears so they won’t rule our lives.

Yet, in discussing Columbine with these young people, who were close in age to my own children, all my arrogant certainty came crashing down. These kids could be our friends, my students said; this could be our school.

My children could have been among the killers’ victims, I realized—and that thought scared the crap out of me. I could be blasé about my own life, but not about theirs.

Often, when I tell my students that “shit happens,” they accuse me of being a pessimist. I explain to them that, in general, I’m pretty happy and convinced of the inherent goodness in the world. It’s just that events from my own life have shown me how little control I have over what happens to me. I’ve made my peace with that.

But not with the terrible things that could befall my children. Not with every car they ride in that I’m helpless to control, with every “friend” I don’t know. Rereading Columbine brought that terror to the fore, despite my efforts to remain detached. Despite my lofty pronouncement that I would never read my kids’ journals (really? even if one of them were suicidally depressed, like Dylan?). Despite my insistence that “shit happens.”

All that fear I thought I’d dismissed years ago? It was right there, leaping up to slap me in the face.

And my students helped me to stare it down. My students, and our discussions, and the writing we all did to try and make sense of the unknowable.

They were my mentors, too. They helped me to do some critical thinking of my own.

One of them missed a class discussion and was still so eager to participate that she wrote the following analysis for me. Her name is Johanna Mustico, and I have her permission to quote from it:

Throughout Cullen’s book, I’ve noticed the writing style above all else. At first, I was put off by his reporter-esque take; to me, the facts weren’t enough. And then, as I continued to read, I realized the facts were more than enough. I felt what I needed to feel when I needed to feel it. Cullen didn’t have to assign the emotion to the moment—the moment lent itself to an emotion. I found myself placing the massacre in my high school, erecting the crosses where the memorial to my classmate (killed by another classmate) stands…

I’ve had an exceptionally difficult time finishing this book. But I’ve taken breaks, and every time, my mind goes back to Columbine. I wonder where the victims and killers would be today if they were still alive…. [W]ould Dylan have found happiness? Surely we may not have heard of Columbine, except for the flower.

Art Information

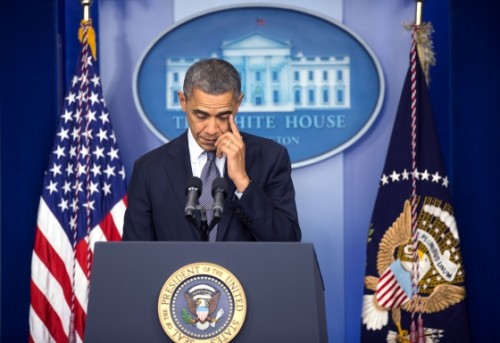

- President Obama delivers a statement to the press regarding the Sandy Hook Elementary School killings, December 14, 2012; official White House Photo by Lawrence Jackson

- "Columbine" © tanakawho; Creative Commons license

Lorraine Berry is an associate editor at Talking Writing. On Twitter, you’ll find her @BerryFLW.

Lorraine Berry is an associate editor at Talking Writing. On Twitter, you’ll find her @BerryFLW.

Even though she is aware of how little control she has over life, Lorraine is an activist. Recently, she organized a teach-in about the events in the Congo, a war that has killed six million Congolese since its beginning in 1996. She may believe that shit happens, but she still does what she can to make a difference.

Teaching Columbine was part of that difference.