Essay by Khalil Elayan

A Gathering of Tribes for Steve Cannon (1935–2019)

Almost a year to the day of this memorial, Talking Writing honors its creative spirit—and the hope that's kept so many artists going during the past months and that we still need this U.S. election week.

Artists have long arms. They have to. They have to be able to reach across town, through alleyways and highways, to reach and tap an unsuspecting shoulder and ask, “Are you an artist, too?”

And so, the long arm of the artist reached out and touched me, and that’s how I came to be in New York City on November 3, 2019, to pay my respects to one who has passed on.

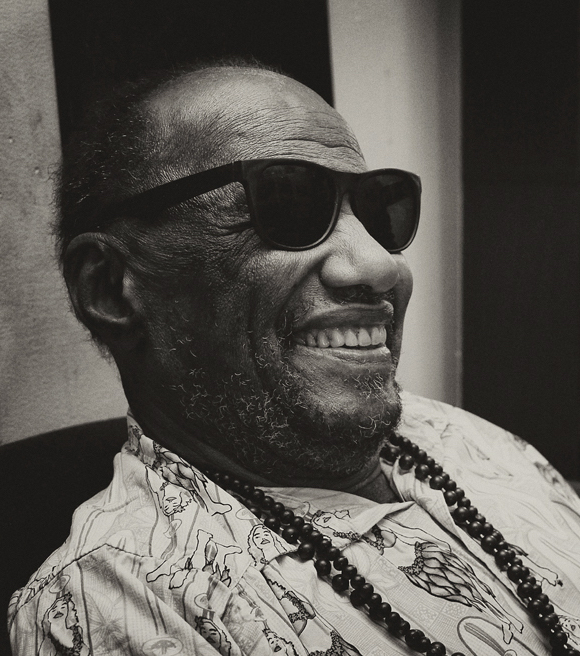

Steve Cannon was a poet, a professor, a publisher, a sponsor, and an influencer. He created a group of poets he called The Tribes, and it was in his magazine A Gathering of the Tribes that my first poem appeared. There was something authentically atavistic about the magazine’s title, something raw and true. This publication was, for many years, an artistic conduit for the Lower East Side. Here, creators of all shades and genders found their way to express themselves, much like we’re seeing today in the dim light of police brutality.

The closer I got to my destination, the more I could see how this island emanates energy. On the bus ride over the East River, I told myself I wouldn’t take an Uber or a taxi, that I would walk the city sidewalks my entire stay. At least this was what I promised myself. Too early to check into my hotel, the front desk agreed to hold my backpack.

Making my way down Lexington Avenue, I snapped pictures of building tops that jutted into the turquoise sky while trying to avoid crowds of talking, smiling, scurrying people who’d just come out of these massive structures to lunch on a sunny day—to stand and munch a gyro near the street vendor from whom they’d purchased their meal—or to sit on a park bench, inadvertently feeding the sparrows and pigeons the crumbs that had fallen from foil or wax paper.

The smells from food trucks and street vendors became an olfactory seduction. I felt like Galahad on his way to the Grail beset by pitfalls. Though tempted, I would resist, focused on what awaited me on the Lower East Side. Perhaps Steve Cannon would rise from the dead and read a poem. But I had long since stopped believing in miracles. I needed a concrete experience, a meat-hook reality. And that’s exactly what I got.

Midtown Manhattan is New York’s navel, but my destination lay forty blocks south and about fifteen east. There, I found a gathering like none I’d ever encountered. I found a haven for artists, the transient ones, the ones who became permanent fixtures, the dreamers, the actors, and— especially—the poets.

You could hear it almost before you got there, palpitating on the tongues of the people beginning to gather, a short declarative sentence: Read the poem. Three words that manifested Steve Cannon’s basic philosophy of poetry.

You could hear it almost before you got there, palpitating on the tongues of the people beginning to gather, a short declarative sentence: Read the poem. Three words that manifested Steve Cannon’s basic philosophy of poetry.

A poem should speak for itself. No explanation necessary. Read the poem. Read the fucking poem!

I would hear these words spoken, shouted, even moaned over the course of six-and-a-half hours, the time it took to celebrate 84 years of a man’s life. Almost four months after his death in July, people were still in the throes of elegiac mania. This, indeed, was a poet. And anyone could see that he must have had very long arms.

I never knew that so many dancers lived in the bodies of poets. That they could jut elbows and hips, knees and ankles in oddly splayed jerks, or that they could sing the blues in operatic atonal bellows. These were the moves, the scenes of a curbside poetry jam.

A bullhorn sounded its primordial radiating call, and the poets gathered. Two women stood in front of the door where Steve had lived and held a poster with his younger face splayed across it. His glasses were crooked, sloping on the left side, and he had a look of supreme ambivalence. The graininess of the picture suggested it had been taken in the 1980s.

I knew something important would begin soon. But the relative haphazardness of it all, the incongruity of the gathering, its cosmic diversity, its color, belied the palpable authenticity. I felt that if I could put on some sort of magic glasses, I’d see arching lines of electricity shooting from person to person.

There were old poets and young poets, street poets and singing poets. All had gathered on the Lower East Side to celebrate Steve’s life in one great barbaric yawp. Next came a jazz group from New Orleans, Steve’s hometown, followed by a local jazz ensemble. The brass reflected the clouds and the tenement tops; I could see entire worlds in those instruments, as if Hephaestus were carving Achilles’ shield anew. I saw bright-colored parasols belonging to those women, family and friends of Steve, who made the trek to New York from New Orleans.

And, for a brief moment, I felt transported to any one of several funerals that could be taking place in the French Quarter or Jackson Square. Except this was no funeral.

Near the steps to the doorway where Steve’s picture was dancing in the hands of his friends, I leaned against an old iron railing and gate. Its sea-green paint was chipped, exposing years of rust and age. Arrowhead tops pointed to the sky, and I snapped a quick picture with my phone. There was a gothic look to this section of sidewalk, but it wouldn’t translate in my picture. Too many umbrellas, too much color, too much movement, too little stoicism and quiet. The air was raucous with yells and laughter. It was enough to wake the dead.

Two hours later, sitting in Tompkins Square Park, cold, with an aching back, I stared at the elm tree where Steve’s ashes were spread. This was Allen Ginsberg’s tree, too. Apparently, Ginsberg would read under it. And here the Hare Krishna modestly declared its om, and disciples were born. After the ashes were spread and the poets shouted, the two bands began to have a dialogue, and old tunes floated up as autumn leaves came down.

I sat down to rest on a park bench, while most of the well over a hundred people remained standing, dancing, and shouting. I noticed that a very old woman, in her mid-eighties at least, was sitting next to me. To my surprise, I recognized her as one of the poets who had spoken at Steve’s house before we made our way to the park. I didn’t remember her name, but she had sharp eyes and a healthy pallor, even if she carried a cane.

She was familiar to me. It was a feeling. After I gave her my name, she swore she’d met me before at some conference or another. It was quite probable within the long arm of shared artistry. We talked of occupation, trauma, and diaspora, typical park conversation. And she was wonderful.

The wind was picking up as the music played on and the troop of celebrating mourners made its way to St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery, where many have gathered before. This was no Sunday morning service or Saturday night mass. Neither funeral nor baptism, yet an odd reaction was on display: a gloried outburst of pain and pride for a poet’s life finally ended. Everyone knew Steve had died months before, but the grief felt fresh, as did the memory of his artistic presence.

This was a waking of exuberant emotions that bounced off brick and sidewalk, tree and human, church beam and stage. It was a halleluiah and not a goodbye. Over the next couple of hours, friends and poets talked and recited. Next, Steve’s favorite pianist was introduced, and he played a tortured atonal piece that probably stirred the spirits of John Coltrane, Cecil Taylor, and Ornette Coleman. Hundreds of us sat on carpeted steps that surrounded the pews full of riveted listeners. No hymns or services, just the words of poets and the beleaguered serenade from the piano.

Following the final words, people shook hands and held elbows. I was introduced to some of his friends throughout the day: more poets, artists, and actors. All beautiful. I wanted to stay and eat with them in the hall, but my mind grew quiet, and the streets of Manhattan beckoned.

I walked back in the dark of the autumn night, thinking about the man I barely knew, an artist who published my first poem, a kindred spirit with a quirky aesthetic. I think now, in this time of plague and quarantine, of violence and protest, of what Steve would say about the madness of some and the resolve of others. He’d be proud of some and wary of others. He would listen for a particular kind of articulation in any given protest and hope that someone could read a poem, one that could speak for itself of a change that will come. Perhaps he’d find some answers, as he always did, among the artists and poets, the weird and the brave.

Publishing Information

- “A Day-Long Celebration of Steve Cannon’s Life This Sunday,” EV Grieve, November 2, 2019.

- “Poet Steve Cannon, 84, of A Gathering of the Tribes” by Lincoln Anderson, amNY, July 8, 2019.

- A Gathering of the Tribes website.

Art Information

- “Urban Ideas,” “Urban Funk,” and “Urban Questions” © John Laue; used by permission.

- “Steve Cannon, Writer and Culture Worker” © ACauthen9; Creative Commons license.

Khalil Elayan is a senior lecturer of English at Kennesaw State University, teaching mostly World and African American literature. His other interests include finishing his book on heroes and spending time in nature on his farm in north Georgia. His poems have been published in A Gathering of the Tribes Magazine, Dime Show Review, About Place Journal, and the Esthetic Apostle. Khalil’s most recent essay appears in Bluntly Magazine. The dominant subjects of his poetry and prose are the disenfranchised, the dispossessed, children who suffer from trauma, and eco-poetry.

Khalil Elayan is a senior lecturer of English at Kennesaw State University, teaching mostly World and African American literature. His other interests include finishing his book on heroes and spending time in nature on his farm in north Georgia. His poems have been published in A Gathering of the Tribes Magazine, Dime Show Review, About Place Journal, and the Esthetic Apostle. Khalil’s most recent essay appears in Bluntly Magazine. The dominant subjects of his poetry and prose are the disenfranchised, the dispossessed, children who suffer from trauma, and eco-poetry.