Editor’s Note by Elizabeth Langosy

What We Talk About When We Talk About Adaptations

As a kid, I saw books and their associated movies as two completely separate things.

As a kid, I saw books and their associated movies as two completely separate things.

I loved J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan, and I loved the 1953 Disney film. I read and reread the books in L. Frank Baum’s Oz series, and I watched and rewatched the classic MGM version of The Wizard of Oz.

I never expected the book and movie versions to be the same, even if they shared a name, characters, and a plot.

But something has changed as I’ve grown older. Now I can't help but compare the film to the book and get cranky whenever I find—as I often do—that the adaptation has sucked the soul out of the story. I fret inside and even boil over (annoying my movie-watching companions) when I consider the havoc wreaked on, say, Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca. I'm sure your thoughts are indignantly flooding with beloved book characters whose depictions on film pulled your heartstrings. And it’s possible my work as a writer and passion for reading have made me view words—and the inner thoughts they can convey—as inviolate, and that I'd enjoy the film versions if only I stopped comparing them to the books.

Or maybe it’s just a matter of semantics. Does it shift the paradigm if a film is called a “retelling?” Am I more comfortable with “influenced by” or “based on?” When does an “adaptation” become a new creative work altogether?

These are the kinds of questions TW writers ask in the November/December 2012 issue of Talking Writing. With “50 Shades of Adaptation,” we’re not only riffing on another popular (and infamous) book title, we’re also referring to the many forms that adaptations, retellings, and mashups can take.

These are the kinds of questions TW writers ask in the November/December 2012 issue of Talking Writing. With “50 Shades of Adaptation,” we’re not only riffing on another popular (and infamous) book title, we’re also referring to the many forms that adaptations, retellings, and mashups can take.Adaptation is an intrinsic component of pop and post-2000 media culture, as writers, artists, musicians, and bloggers appropriate the works of earlier authors and recast them in a dazzling array of new forms. In my cranky mode, I don’t think all the new stuff dazzles, but contributors to this issue offer an array of opinions, pro and con.

In “Why Horror Movies Disappoint Readers,” blogger and fiction writer KC Redding-Gonzalez is firmly in my camp, arguing that most horror films don’t hold a candle to the original books. She notes:

Hollywood’s reliance on special effects, lovingly detailed monsters, and predictable plots annoys my Lovecraftian nature. It tortures my gothic roots.

Lorraine Berry takes on film and book depictions of the Mumbai slums in “Why Did a Manipulative Movie Make Me Cry?” In comparing Behind the Beautiful Forevers with Slumdog Millionaire, she’s frustrated that the astounding narrative journalism of Katherine Boo fails to move her to tears, as Danny Boyle’s movie does.

Later in the issue cycle, Andrew Vanden Bossche explains why he loves Batman, a comic book hero who can be—and has been—turned into every variation of noir detective, gun-slinging enforcer, campy billionaire in tights, and protector of America.

In “Emily Dickinson, Zombie,” Martha Nichols details her unexpected love of poet Paul Legault's loopy takeoff on Dickinson’s poems. For example, he "translates" the eight-line poem "A Word dropped careless on a Page" as:

In “Emily Dickinson, Zombie,” Martha Nichols details her unexpected love of poet Paul Legault's loopy takeoff on Dickinson’s poems. For example, he "translates" the eight-line poem "A Word dropped careless on a Page" as:The only thing bad writers are good for is spreading disease.

Musician and songwriter Mali Sastri does her own form of mashup with Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood. The book helped her break out of a writer's block—and inspired the lyrics for her band's new EP, Private Violence, scheduled for release the day after Mali's essay appears in TW.

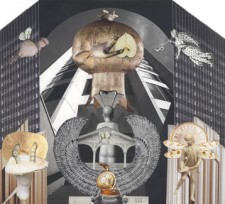

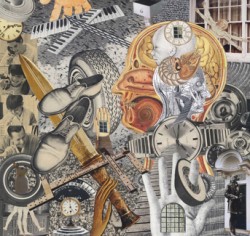

Poets and visual artists also mix it up, crossing genres and mediums. David Meischen explores the shifting boundary between prose poetry and flash fiction. Theresa Williams celebrates the influence of haiku on her own writing. Poet Camille Martin describes the commonalities between her verses and the art she creates from collaged words and images. Visual artist Donald Langosy honors the centuries-old emotional connection between painters and poets.

David Biddle’s Talking Indie column debuts in this issue, too. David will issue regular reports from the brave new world of independent publishing, and in “Sorry, Your Buddies Won’t Buy Your Book,” he recounts his own disappointment when his family and friends didn't immediately download his first self-published novel.

Am I convinced that adaptation is the new little black dress, a great fit for all literary occasions? I hear a new version of Rebecca is in the works, courtesy of Dreamworks, and I’m keeping an open mind. But….

Table of Contents for Nov/Dec 2012

She is greatly enjoying the BBC adaptation of Jennifer Worth's memoir Call the Midwife, although she hasn't yet read the book.

“One of the great things about the online world is that you can be a philosopher and a theologian as easily as the next person." — "Looking for Love in All the Wrong Places"