Memoir by Kent Jacobson

Why Go There, Young Man?

Do you need a crowd-getter? I have a 1963 Oldsmobile two-door in which [civil rights activist] Mrs. Viola Liuzzo was killed. Bullet holes and everything intact. Ideal to bring crowds.

—Birmingham News advertisement (January 15, 1966)

I throw open the windows, and the unfamiliar October air of Alabama wafts into my college office as someone bangs on the door’s frosted glass.

I met Rachelle Baines on my first day a few weeks before. She stormed along alone on a campus sidewalk, she from a Black family with an elderly mother in a nearby shack where you can see the ground between planks in the floor. Now I hold the door, and she crosses into the office and sits unselfconsciously on my desk—bare, butterscotch legs; lightly straightened hair and no makeup; conspicuous cheekbones.

Will. She needs to talk about Will, and it isn’t the first time. “He won’t leave me alone, he won’t stop….” Will Perkins is a student in one of my classes.

The graying secretary’s jaw tightens whenever Rachelle appears (a female student, a young teacher), despite the college’s avert-your-eyes attitude. Rachelle attracts talk. It’s 1967, and we are years from wisdom on relationships between students and faculty.

“Will keeps asking me out. Go here, go there. I’ve got Tim. Will knows that.”

Tim’s a somber philosophy professor twenty years older who’s stayed on longer than most white Northerners and bought a house. He seems dug in.

Not Rachelle.

“I want out of this town, not another homegrown like Will. It’s all crabs in a basket around here, crabs in a basket. You try to crawl out, and they pull you right back.”

She means Will, though she might be talking about Tim.

Rachelle is gorgeous and smart with an athletic fury. She moves and you watch, forward and fluid and never a small step. She stands in front of you and offers herself, as if to say, You can’t ignore me, you won’t ignore me.

I can’t.

“I’ll go north alone if I can find the money.”

• • •

I’m 23 and fresh from graduate school with plans to return to finish a Ph.D., one of the few whites at Tuskegee Institute. A master’s degree was enough for the college in last-minute need of an instructor, even an unworldly Northerner like me, and after several weeks I understand a minimum about the Institute or the students I teach. I understand less about the South except for images on the news: howling men with bats and women with signs—“We hate n*ggas”—as a tiny Black girl in a starched flared dress passes on a sidewalk to integrate an elementary school.

I’d gotten a first live dose two months before.

“What’re you doin’ down here?” At a Birmingham gas pump, a white man in a greased baseball hat spat a chaw at my penny loafers. I was blurry after August days in the car, just short miles away from Tuskegee, the heat melting the station’s asphalt into a nasty stink, my undershorts and shirt soaked with sweat. He’d spotted the Connecticut plates on the rusty old Cadillac with a U-Haul. Civil rights people called this city “Bombingham.”

“Teaching,” I said, “I’m a teacher”—and didn’t tell him where. Teaching had to sound harmless to him. I was harmless.

He rammed the nozzle into my gas tank.

Jesus, what had I walked into? Ex-Alabama-governor George Wallace swore the South had no “colored” trouble until “outside agitators” showed up. We’re the trouble. And true to form, I blundered into Alabama with a sense of superiority, all while “Black riots” (the media’s term) surged in June and July in Boston, New York, Detroit, Chicago, and a hundred other Northern cities. I could appreciate Baseball Hat’s resentment.

He seized the soggy bills I handed him and stalked off.

And following that, I peer constantly into the rearview mirror when I drive: What’s that beat-up pickup with the rifles across the back window doing?

I barely grasp why I’ve come South. I scoured Wordsworth and Browning and the Brontës in grad school, and I felt removed and less than essential. Whatever I yearn for, it’s here in America somewhere and not with the British writers I love. In months, Martin Luther King will die a half-day’s ride up the road in Memphis. Race is ripping my country apart.

Wallace says: “N*gguhs start a riot down here, first one of ‘em to pick up a brick gets a bullet in the brain.” We’ve grown evil. And a tiny Black child in a flared, flowered dress on her way to elementary school pulls at me. I need a place in this life. I ache to be of use.

But I didn’t expect a woman.

I didn’t plan on Rachelle.

• • •

And she isn’t the only surprise. Around the time she came to my office complaining about Will, he and Leon Thomas approach me after class, waiting as others leave. I close the windows. They want privacy. I collect my notes and pens and set them in a briefcase, Dad’s graduation gift.

Will sings in a band with hopes for regional fame. I sang as a boy in a church choir, and Will and I have buzzed outside class about the music we loved growing up. Fats Domino, Larry Williams, Clyde McPhatter, The Moonglows, The Penguins, and the song “It’s All in the Game” by Tommy Edwards. Will tends to speak warmly and then retreats.

Rachelle might be the reason. Or is it my whiteness he can’t trust for long?

Leon has a spiced reputation as a wild man, for saying and doing anything, a reputation heightened by marching in 1965 with Reverend King from Selma to Montgomery in the face of threats and killing by Ku Klux Klansmen.

After the last student leaves, Will and Leon’s smiles hint that the conversation might turn sunnier than I supposed.

Will puffs his cheeks and squints. “Professor Jacobson.”

I asked students to use my first name, in the hopes that the informality might relax me and maybe relax them, too. I knew they’d learn little if I couldn’t break into their caution.

Will’s eyes flicker over my face.

“Is it true…?” He stops, and they both chuckle.

“Is it true white people think we…?”

The class has been uneasily discussing white stereotypes of Black people in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (Ellison was once a student at Tuskegee).

Will’s hand drifts to his groin; he’s too gracious to use the words. “Do they think we are more…?”

The three of us laugh in unison.

So, this is my role, explainer of white foolishness.

“Yeah, they do,” I shrug, palms up in a beats-me expression. “You’re having more fun.”

Leon slaps a thigh and elbows Will.

“That’s what they think,” I say.

Leon and Will nod. They ask nothing else. I confirmed what they suspected, and they stroll into the empty hall, shaking their heads. White people.

• • •

I have no idea whether Black people are any more sexual than anybody else, except white acquaintances think so. And the view appears innocent enough. Most of us like to be considered sexually alive. Leon and Will appreciate the notion. Fun, sex, sure.

Still...

Who wants to be a donkey with a monster pecker?

Or, worse, butchered like Emmett Till.

Will and Leon probably breathed the details. A decade before, the 14-year-old Till visited relatives in Mississippi and allegedly flirted with a white woman. Two locals, one of them the woman’s husband, grabbed the boy from his great-uncle’s home and gouged out an eye, then shot him and wrapped his naked body in barbed wire, bound him to a cotton-gin fan, and dumped the corpse into the Tallahatchie River.

• • •

A quiet day in November. I straighten up the office, gather books, and hope for dinner at the greasy spoon where I’ve seen Black diners smiling whenever I wander past. I switch off the lights and open the door.

Rachelle freezes, clutching herself near the door, her chin trembling, and she won’t look at me.

“Sis….” She mumbles phrases I can’t untangle and finally sits in my office after some coaxing.

She stares into the rug.

A sister, it turns out, is visiting from Detroit, and she’s unloaded. The “sister” says she is really Rachelle’s mother. The elderly woman Rachelle calls “Mama,” Rachelle’s deepest love, is in fact her grandmother.

“Who am I now?” Rachelle hunches in her hard, wooden chair, a palm raised as if to ward off the old beliefs. “They lied to me.”

Her “sister” and “Mama” have never said who Rachelle’s father is, because he could reveal the truth about her actual mother. Even today, she tells me, they wouldn’t say, although Rachelle has pressed them on the subject for years. She rocks back and forth in the chair as she speaks, still clutching herself. A child of a man her family won’t discuss, Rachelle has no father, and the shaky status gnaws at her. And spurs her.

“Where do I live after this? With my ‘sister’?”

I twist in my seat.

“Will you take me to town so I can buy a few things for school?”

I missed the transition.

“I need things.”

I’m guessing she wants to hide in the routine, settle herself, forget for a time. But downtown. The college section with no noticeable Southern whites, and almost a mile away, provides a sanctuary for students and us faculty. The white-owned, white-run stores downtown—a different matter. I haven’t gone in the months I’ve been in Tuskegee.

Even so, I lack supplies, yellow paper and certain pens I can’t find on campus. Rachelle understands how downtown works.

“Sure, let’s go. Show the way.”

• • •

I drive Rachelle to a square of tired buildings and park on a narrow street next to a statue of a Confederate soldier. It’s just feet away from the alley where police found the body of Rachelle’s friend, Sammy Younge. Only months before, he’d helped poorer Black people register to vote at the courthouse, and he’d made for the white restroom at the Standard Oil station across the square, where the attendant stopped Younge with a .38.

Rachelle and I enter a windowless store with a low ceiling and meager light, the shelves and floor sheeted with dust. A middle-aged white woman glares at us from the register, and Rachelle doesn’t look back. Whites consider eye contact from a Black person insolent.

My tweed jacket marks me as a teacher at the college, one more do-gooder, the woman probably figures, sniffing around another “colored” tramp.

I go in search of pens and paper as Rachelle slips down an aisle. I can hear the school secretary: Why go there, young man? You’re what the white folks hate, the races mixing, and the girl knows better. Someone, perhaps you, perhaps us, will pay for you-two’s blindness.

I don’t care.

I haven’t come to Alabama to fuel the race war, yet in this moment, in this tiny Tuskegee shop, I’m not a harmless bystander anymore. Rachelle and I are hollering—Fuck your cracker rage.

I lose Rachelle, then join her by the register and wait, Rachelle ahead of me behind a group of white women I hadn’t noticed. We wait, and the women and the clerk take their time, none of them in a hurry. Rachelle and I seem not to exist for them despite the frequent peeks.

Finally, the three exit for the street, and it’s our turn.

The stout clerk gazes right past Rachelle at me, “Can I help you, sir?”

Rachelle and she stand inches apart, separated by the narrowest counter, the clerk locked on my stunned face. Whites served first.

A pickup roars just outside.

Rachelle sets three yellow #2 pencils in front of the clerk along with a Three Musketeers bar, and my eyes follow her deliberate walk to the door.

Someone in back could have a gun.

• • •

Rachelle glowers through the windshield as I settle behind the wheel and touch her arm. She winces and won’t talk.

I’m thinking she intended the trip downtown for minutes together. Still, there were safer options like the coffee shop near school. Maybe she needed to show me how she suffers in the South, how white people always deal crap cards. With her “sister” urging her to bolt north, she would challenge custom a last time to see if the city uprisings in the summer had altered anything in town. Or it could be, foolishly, she hoped my professorial demeanor, however young I appeared, might change the whites-first practice once.

I changed nothing. I suspect Tim changed nothing, too.

Black men in pinstriped suits I saw in Montgomery and Birmingham absorbed insults like the shop woman’s. They nodded, they smiled, they feigned indifference. They accepted Alabama or pretended to, whatever defiance they carried invisible. Rachelle’s defiance isn’t. She refuses to be classed a lesser-than.

I descended on the South feeling exalted. “Gentlemen,” the college deans called us. And I spun into a professor in Brooks Brothers’ herringbone, more upstanding than the gas jockey in Birmingham and the shop clerk in Tuskegee and, worse, more upstanding than their Black victims. A voice in me whispered constantly, Anyone worth their salt would quit this hole.

And now I wonder where they’d go. You can’t outrun your skin. The recent uprisings in the North only prove the racist swamp has burst its Southern banks. My dad claims heavyweight boxer Joe Louis “understood his place” and that the current champion Muhammad Ali, who opposes the Vietnam War, doesn’t. Multiply my dad’s New England outlook by white millions, and you have another clue that the swamp churns nationwide.

I sit on no high perch. I represent one more troublemaker to white Alabama, no more exalted than the “coloreds” who press to organize and march and vote and not heed the tag Does Not Qualify.

And yet I lack Rachelle and Leon and Will’s grit, their trek within a country that flays and shames and degrades and might kill them. How long can they last unharmed? How long can I?

• • •

I trudge for home days later, fat folders of English papers in my briefcase, and cross a yellow patch of campus green. The trees provide small protection from the sun, but a breeze washes my face.

Rachelle waves her hand.

“Let’s go dance Saturday. Will’s band’s playing outside town.”

A car passes too slowly.

“I’ll ask Desree.” Rachelle senses my resistance. “She should get out. She hasn’t been the same since Sammy.”

“What about Tim?”

“He’s busy and won’t mind if we all three go. He hates to dance.”

Tim plans to stay in Tuskegee. She and he may be verging on an end.

“Who goes where Will’s playing?” (And what happens when I stroll in with you?)

Rachelle glances to the street.

Black faculty don’t go to roadhouses, too backcountry for them.

“It’s Will’s band. How bad can it be? Come on, you’ll like it. You dance, don’t you?”

Two Black women and a white guy in the middle of East Jesus. We’d dip into worse than downtown.

• • •

Saturday night, and it’s hot, and we climb into my wrecked Cadillac. I would inhale another Alabama, I tell myself, Will, the music, the countryside. Suck it up, forget the threat. If Rachelle can do this….

I met Desree Jefferson every so often, and each time she talked about returning to college at Howard, and then about staying home in Tuskegee, and then she’d try Atlanta. She seemed undone—her droop, the scuffle step, the muted speech, the drifting focus. Sammy Younge and she had been friends since childhood, and she watched a white jury acquit his murderer in an hour.

I drive under Rachelle’s direction, Desree in back, and we follow a rutted, patchy, one-lane road without a middle line, nosing across farm fields that run flat for miles. No lights, no cars, no houses, no barns. A hush in the car, and I grip the wheel tighter. “You know where we are?”

Rachelle: “We’re almost good. Drive. It’s out here.”

We’ll vanish in this emptiness, the three of us dumped in a gully off a dirt path, the car torched, and five hundred FBI agents and federal troops won’t find us, even if they did find what was left of those civil rights workers in Philadelphia, Mississippi—the Black Chaney and the white New Yorkers, Goodman and Schwerner.

A mass of derelict trucks and cars looms ahead, parked around a long, low, weary building, a rusted Drink Coca-Cola sign beside a weathered door of vertical planks. Cigarette smoke, loud talk, the raunchy sweetness of rhythm and blues. Heat pours from the windows.

Desree and Rachelle wear the thinnest of dresses. I’m in a polo shirt, jeans, tennis shoes, and stale sweat. We edge into a murky room heaving with dancers, the air gooey with liquor and every kind of perfume. Not a white face.

The song ends, and the dancers slide into a slow, thick silence. Eyes fix on me, the white boy with the two Black women. The male scowls say, Honkies show any damn where and figure they own us. Get the son of a bitch out. He brought women? This is Alabama, pretty boy.

Rachelle and Desree slip into the crush, and I camp at the door and glance left to Will by a microphone. He waves me in. He waves again. Come on in, come on in.

“People, this is my teacher, Professor Jacobson at the college. You’re welcome, Professor J. You’re welcome. Say hello.”

I lower my head and force a smile, and the band plays my favorite song, Tommy Edwards, “Many a tear has to fall….” Conversation stirs, and laughter. They love Will. White boy won’t spoil this party.

I search for Rachelle as the Edwards song plays and find her in a friendly cluster.

“You really a teacher at the college?” a woman asks.

Rachelle spreads her arms high and thrusts her pelvis out, eyes wide, head tipped back, dancing. We’re good, her joy says, we’re good. We’re safe: on this floor, in this room, with Will’s band, inside this battered, forgotten, falling-down roadhouse.

We aren’t safe. No one’s safe. Rachelle knows it, and I know it, yet I understand the hunger to make a home all the more in a bitter place, to throw acid at tooth-and-claw custom, to sink your feet in the mud where you find them, to be who you are.

I can begin my life in this bitter place.

“Time to dance,” Rachelle says. “Time to dance.”

Afterword by Kent Jacobson

I grew up in a tough Rhode Island mill town, but I wasn’t ready for Tuskegee, Alabama, in 1967, only months before Martin Luther King, Jr., was killed in Memphis a few hundred miles away. Yet my experience at Tuskegee Institute led to thirty years of teaching in Black and Brown settings, including an inner-city Great Books program—Bard College’s Clemente Course in the Humanities—a 2015 winner of the National Humanities Medal from the Obamas.

I have changed names, except my own, for the purposes of privacy. The names of historical figures—King, Sammy Younge, Michael Schwerner, James Chaney, Andrew Goodman—have not been changed.

I instinctively framed the writing without the present me, even after so many years’ work with non-white people. Recapturing some of how it felt the first time became an end: I was 23 again and green. Personal history like “White People” allows the writer and the reader to come in a side door to a difficult subject. I wanted to talk about racism without putting us all back on our heels. Writing this story has helped me untangle some of my earliest acquired feelings about race, and I hope the attempt to detail my initial plunge into a Black world will open readers (especially white readers) to their own, often-veiled beliefs about race.

Publishing Information

- The ad from the Birmingham News on January 15, 1966, was quoted in a UPI story that the New York Times printed two days later: “Liuzzo Seeks to Bar Sale Ad for Car in Which Wife Died,” New York Times, January 17, 1966.

- George Wallace (“start a riot down here”) is quoted in “The Return of George Wallace” by Marshall Frady, New York Review of Books, October 30, 1975.

- Sammy Younge, Jr.: The First Black College Student to Die in the Black Liberation Movement by James Foreman (Grove Press, 1968).

- In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s by Clayborne Carson (Harvard University Press, 1981).

- “Marvin L. Segrest, Samuel L. Younge, Jr.—Notice to Close File” (File No. 14-2-1431), Civil Rights Division, U.S. Department of Justice.

- Murder in Mississippi: United States v. Price and the Struggle for Civil Rights by Howard Ball (University Press of Kansas, 2004).

Art Information

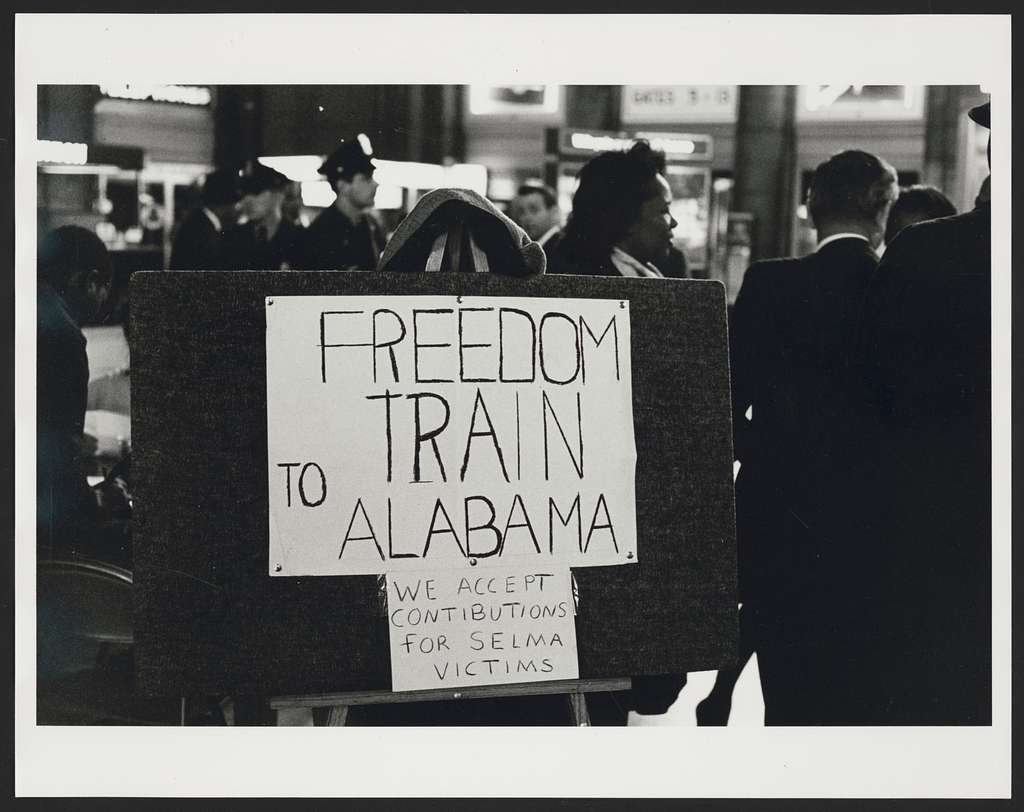

- “Freedom Train to Alabama” © Peter Pettus; public domain.

- “Vivian Malone Entering Foster Auditorium to Register for Classes at the University of Alabama” © U.S. News & World Report; Warren K. Leffler, photographer; public domain.

- “Marchers at the March on Washington, 1963” © Marion S. Trikosko; public domain.

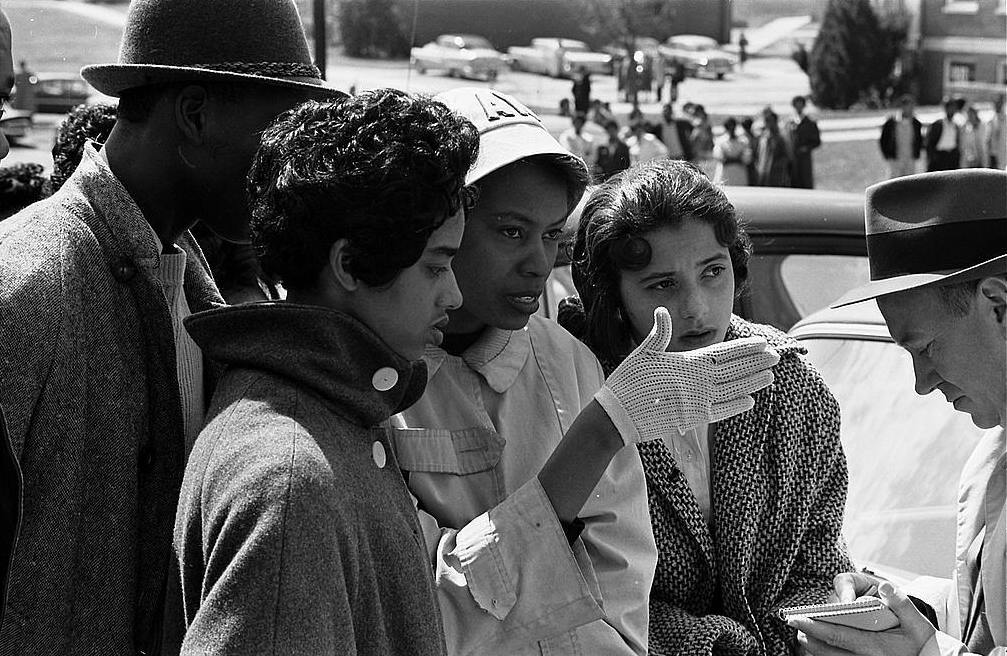

- “Students of Alabama State College” © Thomas J. O'Halloran; public domain.

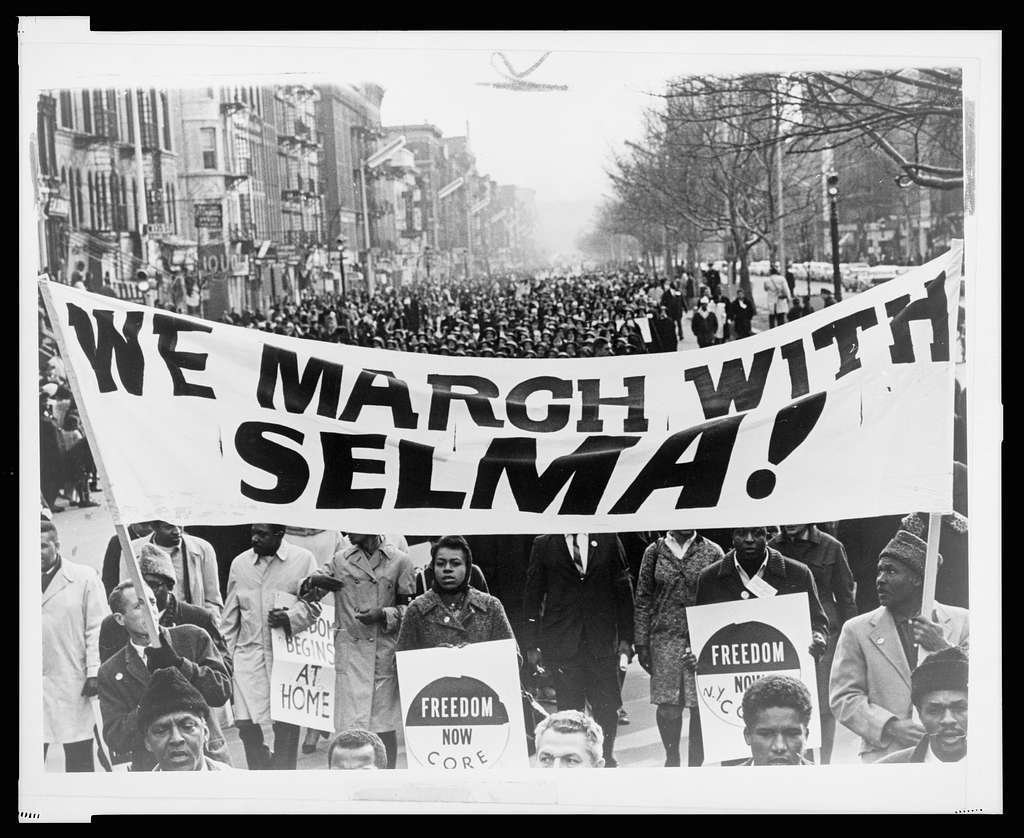

- “Marchers Carrying Banner Lead Way as 15,000 Parade in Harlem” © New York World-Telegram and the Sun; Stanley Wolfson, photographer; public domain.

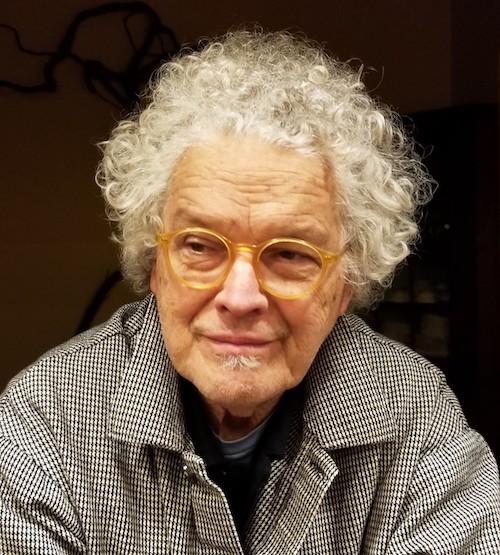

Kent Jacobson has been a teacher, foundation executive, and documentary filmmaker. His nonfiction has appeared in Hobart, Under the Sun, Punctuate, iTeach, and elsewhere. He lives in western Massachusetts with his wife, landscape architect Martha Lyon.

Kent Jacobson has been a teacher, foundation executive, and documentary filmmaker. His nonfiction has appeared in Hobart, Under the Sun, Punctuate, iTeach, and elsewhere. He lives in western Massachusetts with his wife, landscape architect Martha Lyon.