Essay by JoeAnn Hart

Making the New Yorker—and Shesha the Snake

Halfway through a writer’s residency on Martha’s Vineyard, alone on an isolated cove with just my notes, books, and the deer of Edgartown, Massachusetts, the project I was working on stalled. Nothing seemed to fit together. Never again, I swore. Never another jigsaw puzzle.

A friend had given me the thousand-piece puzzle, and even though I hadn’t done one since childhood, in the winter of 2016 I took it with me to Turkey Land Cove Foundation, a spacious retreat for one lucky resident at a time. Prepared meals with cooking instructions were quietly delivered every two days, and someone tiptoed in to clean once a week—the extent of human/writer interaction. I envisioned brittle February nights by the fire, the puzzle laid out before me as I transformed chaos into order, piece by piece, like a good mystery novel.

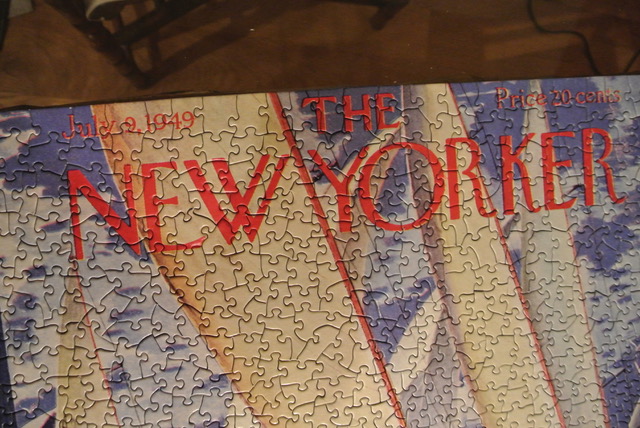

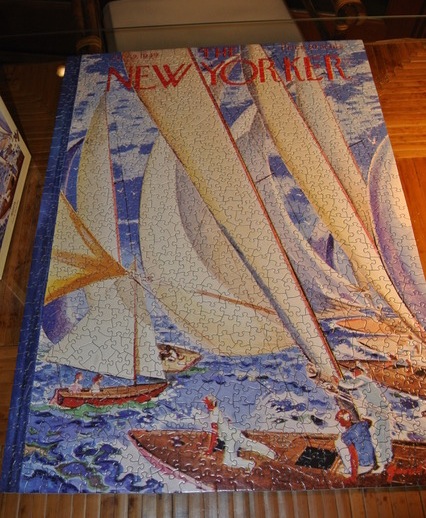

Completing the puzzle would be a mindless corrective to a day spent writing a play, a dark comedy whose very subject was chaos: hoarding. It was an illness I’d wanted to write about for some time, and the spectacle of a house crammed with teetering stacks of magazines, empty frames, bags of stale food, broken chairs, and other visual clutter begged to be on a stage. I’d written novels, but never a full-length play, so drafting one would be as much of a puzzle for me as the actual puzzle, and I had two weeks in which to figure out both. Best of all, the jigsaw depicted a 1949 New Yorker cover of a yacht race, complete with billowing sails, crashing hulls, and masts asunder. A New Yorker puzzle at a writer’s residency—how perfect was that?

When I arrived at the house, past lanes of scrub oaks and boarded-up summer homes, I set up my computer downstairs in the studio space and unpacked my books, all variations on How to Write a Play. On the bulletin board, I posted inspirational quotes along with words based on Aristotle’s six elements of drama—Character, Action, Ideas, Language, Music, and Spectacle—each hand-lettered on its own card.

The puzzle box went upstairs to the living room, where I centered it on a card table facing the panorama of the frosty cove. After dinner, I broke the seal and emptied the contents, scattering the pieces like a starry constellation across the table. I flipped them all face up, then went to bed with a playwriting book under my arm.

The next morning, I opened a Word document labeled “Play Notes,” thousands of discrete words that seemed to have nothing to do with one another. The book I’d read the night before suggested I start with an outline, but how could I write an outline for something I knew so little about? There was no picture on a box to guide me, as there was with the puzzle. All I had for sure were a few characters—a hoarder and her daughter; an absent father; and Shesha, an enormous snake bought by the hoarder to control vermin attracted to the trash. So, I went straight to the drama and started writing dialogue (“A boa? You got a snake to take care of the rats?”), hoping I’d fill in my story as I went along.

That night, I poured myself a glass of wine and stared at the puzzle pieces, which, like my notes on the play, seemed to have nothing to do with one another. An outline for this, too, seemed in order, but identifying the flat-edge pieces to create the 19” x 27” frame was not as obvious as I’d assumed. Internal pieces can have deceptively straight edges. I opted instead to organize by color. In the same way I had documents marked “constrictor” or “hoarding,” I had groupings of “brown hulls” and “red logo.”

As the days went by, I made progress on the play, but since sitting is the new smoking (and how I wished I still did that), I got up every hour to put water on for tea. I’d stand over the puzzle while waiting for the boil, and if I had a good run of pieces, I’d go downstairs expecting an equally good run of words, as if I were living out my own The Puzzle of Dorian Gray.

I'd anticipated trouble with the play, since I didn’t know what I was doing, but the jigsaw puzzle was surprisingly hard. I didn't have to invent a world from scratch, but arranging bits of cardboard was like working with words in that they both defied easy placement. Color, or the lack thereof, was a particular challenge; the space between the logo and hulls was mostly fifty shades of white. White clouds against a white-capped sea, white sails with white rigging, white sails in white shadows.

There were pieces that fake-fitted, which stalled any progress until they were found out, much in the same way I would write half a scene for my play before realizing it didn’t belong. Then there were pieces that slipped into place by accident, as they do sometimes in writing—as when I created an old boyfriend for the daughter not knowing his purpose. Later, when I needed a health inspector, he was already in place to carry the plot of eviction. Still, the more I wrote, the more I struggled to find the connective tissue that would hold it all together.

One week into the residency, I realized I wasn't halfway done with either my play or the puzzle. I was loath to leave the island without a rough draft of the play, but this now seemed a possibility. The puzzle, on the other hand, I’d always assumed I would finish. I became convinced that pieces were missing, and my paranoia increased when I actually found one on the floor. I closed my eyes at night, and I saw puzzle pieces. When I opened my eyes in the morning, I saw an interlocking world.

I thought of Hemingway, who famously wrote in A Moveable Feast that he would look over the mansard roofs of Paris and say to his young self, “All you have to do is write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence that you know.” I would look out over the cove, clutching a recalcitrant bit of cardboard, and say to myself, “All you have to do is get this one piece placed—this one true piece.”

The good news is that I hardly thought about the play when I was away from my desk; no worrying it to pieces or allowing self-doubt to prevent it from being born. Answers to problems I didn’t know I had came to me while concentrating on the puzzle. While trying to patch together a length of rigging that I hoped would make the puzzle come together, I suddenly thought of Shesha the snake. She had to pull the play together. So, I wrote a cameo for her in every scene. I had her slither through the piles of possessions in view only to the audience, reinforcing the theme of environmental terror.

The good news is that I hardly thought about the play when I was away from my desk; no worrying it to pieces or allowing self-doubt to prevent it from being born. Answers to problems I didn’t know I had came to me while concentrating on the puzzle. While trying to patch together a length of rigging that I hoped would make the puzzle come together, I suddenly thought of Shesha the snake. She had to pull the play together. So, I wrote a cameo for her in every scene. I had her slither through the piles of possessions in view only to the audience, reinforcing the theme of environmental terror.

On the last day of the residency, I heard the swelling of my internal orchestra as I finished both the puzzle and the script. I didn’t yet know what I had in the play, but a puzzle can’t be done incorrectly—slowly, yes, but not flat-out wrong. I took some photos and put the pieces back in the box, as if I were breaking down the set of a play. I put it in the games cupboard for the next resident and left for the ferry, feeling quite grand, as Hemingway would say.

Publishing Information

- Turkey Land Cove Foundation website (writing residencies for women).

- A Moveable Feast by Ernest Hemingway (Scribner’s/Simon & Schuster, 1964).

Art Information

- “New Yorker Puzzle 1” © JoeAnn Hart; used with permission.

- “New Yorker Puzzle 3” © JoeAnn Hart; used with permission.

JoeAnn Hart is the author of the novels Float and Addled. Her short fiction, essays, and articles have appeared in a number of publications, including Orion magazine and the anthology Black Lives Have Always Mattered.

JoeAnn Hart is the author of the novels Float and Addled. Her short fiction, essays, and articles have appeared in a number of publications, including Orion magazine and the anthology Black Lives Have Always Mattered.

For more information please visit JoeAnn Hart’s website. Visit her on Twitter @JoeAnnH.