Essay by Lloyd Sy

Remembering in Dollars and Cents

Allegedly, my father is only the fourth-cheapest member of his family, beaten out in penny-pinching by two older brothers and the queen bee: my exacting, terrifying maternal grandmother. There was no guiding ideology in the Sy household higher than this fixation. Our meticulous attention to finances didn’t come from dire need (both my parents are physicians), but from a belief that the primary function of a dollar is to not be spent.

We are not, my father has told me, merely holding onto money, but actively refusing its wanton disregard, counteracting the (white) American way of purchasing candleholders, new TVs, designer clothing, Crayola crayons. Our family, having survived two translocations in a century—first from China to the Philippines, then to the States—spends only on that which we need, and on that, as little as possible. Sunday mornings are for cutting out coupons to be placed in the (garage-sale-bought) red coupon bag. Above all, every purchase must be tracked to dispel any ugly merchant tricks and ensure that our meager tips were never misread.

Always keep your receipts.

Here’s an uncommon ritual for a kid growing up in Rockford, Illinois, in the late 1990s: Every three months, I dug through the Reebok shoebox full of receipts underneath my parents’ bed and listed off the date, the seller, the price. My mom held the latest credit-card statements in one hand and a pen in the other, ready to check my report against the bill. Off a few cents? Time to make a call.

I have handled hundreds of receipts in this way. I have known them glossy or scratchy, faded or vigorously inked, square or CVS. I have known every permutation of date, month, and year. I have known receipts stapled onto two or three other receipts, augmented by returns, rebates, store credit. I have known the ways in which receipts fold into each other, the feel of a receipt that probably holds another, smaller receipt inside.

I have heard the difference in crinkle between a crushed-up Menards and a crushed-up Mobil Gas receipt. I have seen lovely back-of-the-receipt designs and graphic designers’ worst nightmares—yellow receipts, green receipts, blue receipts, and receipts whose animated giraffe has bled due to water damage, rendering the surrounding paper mildly gray. I am an expert in finding all the pertinent information on a multi-paged hotel receipt and shredding six receipts at one time.

I know receipts, know how to find their most pressing data: when we did something, where we did it, how much life cost. Receipts, for all their fixation on a particular time and place, actually mark processes, stretches of time. Our bedrooms are made of objects whose existence and exchange is legitimized, legalized, and recorded on some piece of paper, somewhere. From the Medieval Latin recepta (received), receipts, those monotone scraps, indicate the kind of life we’ve decided to receive.

For reimbursement forms and monetary disputes, it is evidence. But more than that, the receipt confirms that, yes, it happened, and you may touch it. The time becomes real, its stringent, mechanical expression belying a warmth of potent memory. I wonder that my beloved items can be represented in such humble fonts, such weak and ephemeral ink.

I have a shoebox in my bedroom full of memories, many of which are receipts: the ticket stub from my first movie date, a lunch receipt after I graduated college, a proof of transaction for a stuffed pink bunny. I like to think I’ve discarded the extreme frugality my family attempted to instill in me. In high school, I spent money on many unnecessary things. Most of all, after-class fast-food meals with Jason and Filip, my two Great Friends in high school. We called ourselves, immaturely transgressive, the RMFs (“Raw Motherf***ers,” coined by yours truly).

Jason, over the past five years, has dropped out of engineering school to pursue firefighting and became a Jehovah’s Witness to marry the mother of his child. Filip’s story is more interesting: A Serb born in Bosnia in the midst of the Yugoslav Wars of the 1990s, Filip was granted refugee status, moving to our nondescript city with his mother and grandparents in 2001.

Growing up in a small apartment in one of Rockford’s most impoverished neighborhoods, Filip entered the city’s magnet program in high school. Humorous, witty, and loyal, he quickly established himself as the finest history student in our city. And he befriended Jason and me, which gave him two cars to sit in before or after school and two people to talk to every night, at 9 p.m. Central Standard Time (when our cell phone minutes didn’t count toward the monthly total).

Being our friend helped, I hope, a little bit, a tiny bit, when Filip’s mother Dragica passed away from cancer on April 23, 2011, in the middle of a Saturday that happened to be my seventeenth birthday. Having lost his grandmother four years earlier, also to cancer, Filip was left in charge of his household—a few thousand dollars of savings in the bank, the old dingy place on Halsted Road, a grandfather with diabetes and Alzheimer’s. He had to collect welfare checks, to bring his grandfather to dialysis, to pay rent. He grew up faster than any of us—and maybe grew up when none of the rest of us could.

Being our friend helped, I hope, a little bit, a tiny bit, when Filip’s mother Dragica passed away from cancer on April 23, 2011, in the middle of a Saturday that happened to be my seventeenth birthday. Having lost his grandmother four years earlier, also to cancer, Filip was left in charge of his household—a few thousand dollars of savings in the bank, the old dingy place on Halsted Road, a grandfather with diabetes and Alzheimer’s. He had to collect welfare checks, to bring his grandfather to dialysis, to pay rent. He grew up faster than any of us—and maybe grew up when none of the rest of us could.

Filip may not have needed Jason and me to go to his apartment on the day after his mother died, to embrace him and drop off some grocery flowers. But he came, graciously, out for an hour with us. In the midst of suffering, he joined a straight-faced celebration of our traditions, a refurbishing of our afterschool activities into the stuff of mourning and confrontation with the adult earnestness coming rapidly on the horizon.

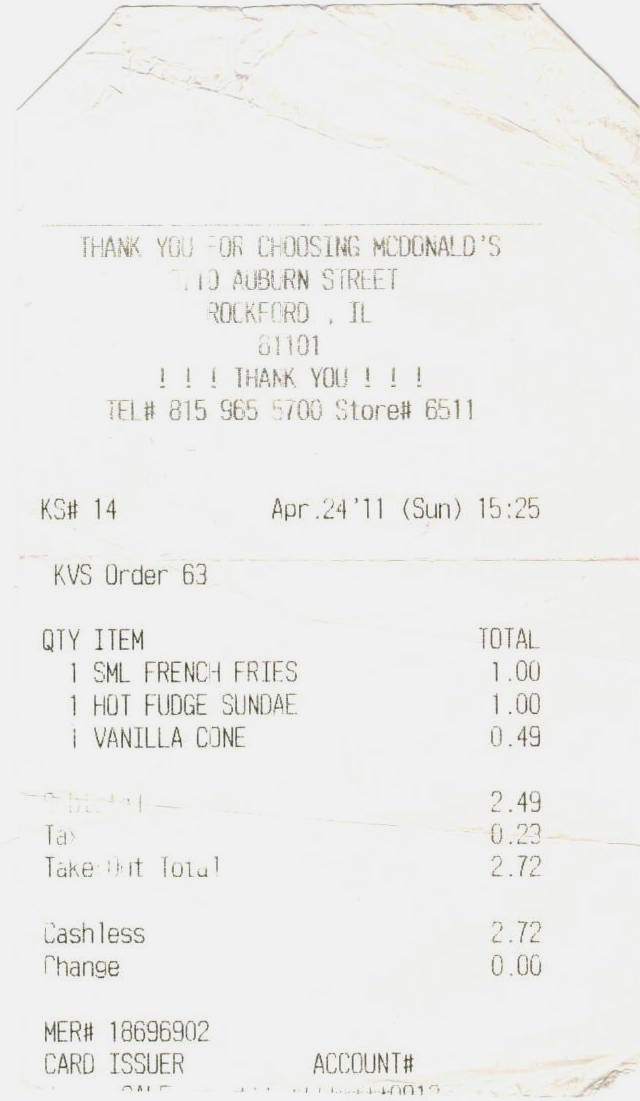

I saved the receipt: my hot fudge sundae, Jason’s cone, Filip’s fries. Jason drove. A sunny day; the ice cream melting. Nobody said much of anything. It was just we three, convincing ourselves that the ice cream machines at the Auburn Street McDonald’s still worked, that life would go on as usual. Of course, it soon would change. We went to college a year and a half later. Filip earned a full scholarship to Princeton, and we have rarely been in the same city at the same time since.

We have never been back to that McDonald’s together. Perhaps on that day it was assumed into heaven. We can’t go back again. Bear with me: Sometimes I trace the end of my boyhood to eating that drive-thru hot fudge sundae next to my two best friends on the day after Dragica Karadzic received her wings. Useful, I think, to know exactly when it occurred—to be able to handle delicately, in my fingers, the actual day I began to grapple with this thing called Real Life.

Art Information

- “Hoping My Art Becomes a Financial Instrument for the Super Rich” © Nelson Lowhim; used by permission.

Lloyd Sy is a writer and Ph.D. candidate in English at the University of Virginia, where he is completing a dissertation on deforestation in nineteenth-century American literature. This is his first published piece of prose.

Lloyd Sy is a writer and Ph.D. candidate in English at the University of Virginia, where he is completing a dissertation on deforestation in nineteenth-century American literature. This is his first published piece of prose.