Image Essay by Theresa Williams

According to family mythology, I was a wanted child. My parents already had two boys, ages 8 and 10, and they wanted a girl.

I grew up hearing the story of my birth, and the story would give me a warm glow.

I grew up hearing the story of my birth, and the story would give me a warm glow.

“Is it a girl? Is it a girl?” my father had asked anxiously, as they wheeled my mother out of the delivery room. And for a few years, things were good for me. My mother bought me pretty dresses, curled my hair, and took lots of pictures.

However, as I grew older, I came to suspect I was not the child my mother had wanted. She was brash, a gossip. I was quiet and bookish. She was domestic, and my thoughts were filled with fantasy.

By the time I was ten, it had become harder and harder for her to dress me in pretty clothes, like a doll. She didn’t know what to do with me, and we grew apart.

Years later, after I’d had children of my own, a hometown neighbor, Arlene, told me about a conversation she’d had with my mother after I moved from North Carolina to Ohio to study writing:

Arlene: I know you must really miss Theresa and the kids.

My mother: I miss the kids.

I don’t know why Arlene shared this with me, but I believed the conversation had taken place. It sounded so much like something my mother would say. I’d watched how she lavished attention on my children that she’d never given to me. Even as my boys reached their teen years, she continued to dote on them.

And so I came to realize: My mother loved me, but she didn’t like me.

This truth about our relationship is something I’ve wanted to explore for years. My comics series, The Goat Child, gives me a way to do that. The Goat Child is based on a favorite childhood toy. At the same time, The Goat Child is me.

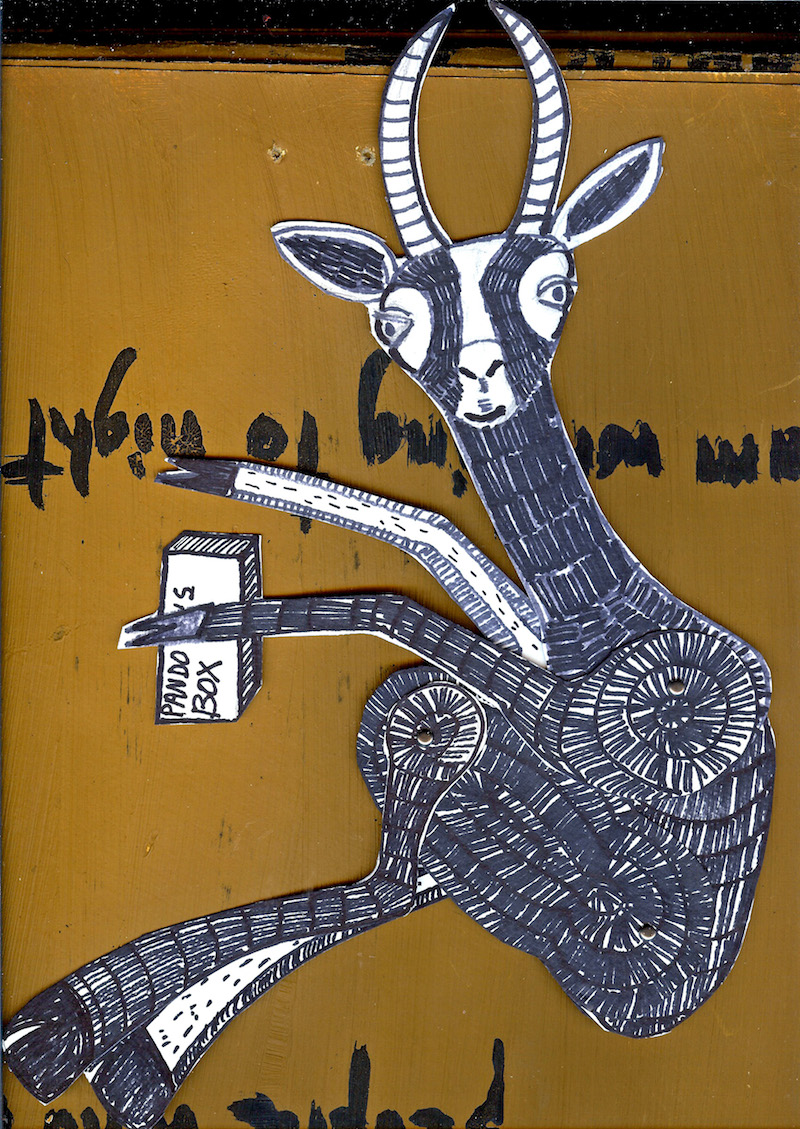

The Goat Child stands for everything I feel exceptionally tender about. My favorite toy when I was a child was a little plastic goat, which was lost at school when I was in the third grade. I’d played with him every day for three years. All of my toys were “rescued” toys—from cereal boxes and so on—but the goat was special because he came to me with a story. My elder brother brought him home, saying he found him abandoned on the highway. It broke my heart. I not only took him in, I made him king of all my tiny toy animals. In my imagination, he became a great warrior, fighting many battles against obstacles.

My little toy goat kept me company when I was lonely and helped me work out my unhappiness. When I pushed him to overcome the obstacles I created for him, I learned how to overcome my real ones.

When I’m creating stories about The Goat Child, I can touch upon my childhood, which hurts, but I can also indulge in the delight of creating a fairy tale.

The Goat Child is a holy figure in the way Richard Brautigan defines it, in the sense of ordinary life being extraordinary, of the outcast being a kind of hero. In Brautigan’s Trout Fishing in America, a child’s imagination turns water and a bit of flavored powder into a powerful elixir. This ordinary child becomes like Christ, turning water into wine—or, in this case, Kool-Aid.

The Goat Child is not Christ, but like Brautigan’s “Kool-Aid wino,” he’s a Christ figure. I’m not interested in doing what C. S. Lewis did in The Chronicles of Narnia, crafting a Christian retelling. But I am interested in religious stories as a template for secular stories.

• • •

It took me a long time to know how to tell the story of The Goat Child.

He first found his way into a series of prose poems in which he was an Everyman and philosopher like Zbigniew Herbert’s Mr. Cogito. Then I put him into a long fairytale that I hoped would turn into a novel. But I became trapped into telling an adult story and began to rely too much on sarcasm and wit. I saw that by using these forms, I was losing the childhood magic that had made my toy real to me.

My reverence for comics began recently, when I ran across an article on the Internet called “Seth on Peanuts: Comics = Poetry + Graphic Design.” I had read the Sunday funnies when I was a child—who didn’t? But I never read comic books. I never cared about Superman, Batman, or Wonder Woman. My capacity for appreciating satire was slight, so Mad Magazine was beyond me.

In the article I read, Seth—the award-winning Canadian cartoonist best known for his series Palookaville—says:

Comics are often referred to in reference to film and prose—neither seems that appropriate to me. The poetry connection is more appropriate because of both the condensing of words and the emphasis on rhythm.

As they say in the funny papers, Crash! Boom! Pow! I knew that this would be my format for The Goat Child. Seth had shown me that comics can be a serious and worthy undertaking. I remembered that storytelling is storytelling, whatever form it takes.

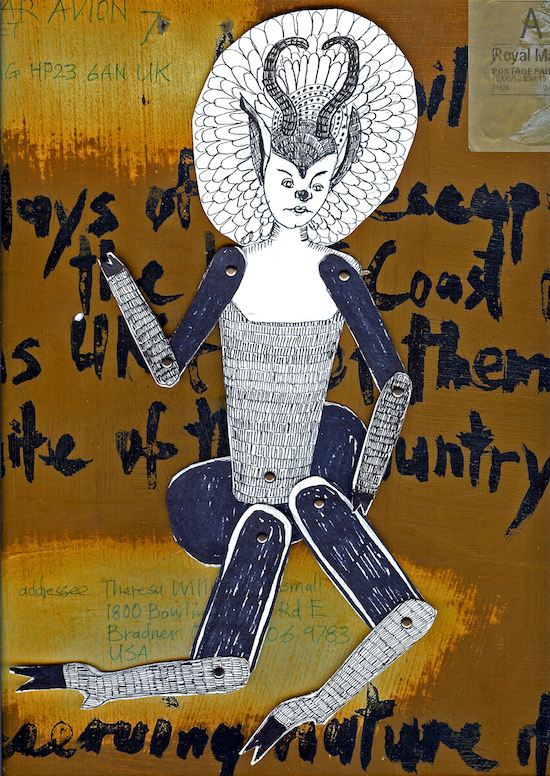

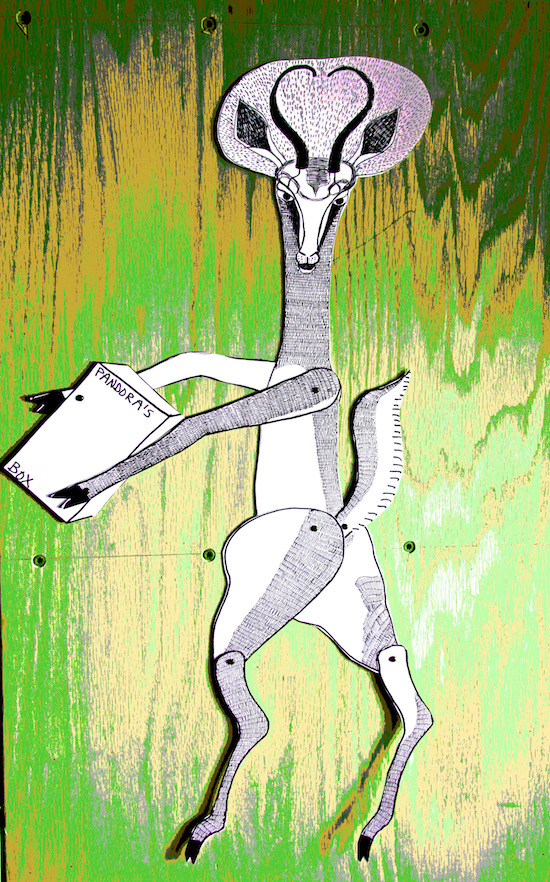

From there, I began to think a lot about what I wanted The Goat Child to look like. My childhood plaything was a cheap plastic toy, the kind that comes out of a bag of safari animals. But I wanted my character to have human attributes. I experimented first by making a few paper dolls:

While working on these dolls, I decided that my childhood toy was only part of why I was drawn to horned animals like deer, antelope, and goats. These are all liminal creatures, creatures of the borderland occupying that place between ordinary life and the imagination. Frida Kahlo, a favorite artist of mine, painted herself in the likeness of a deer.

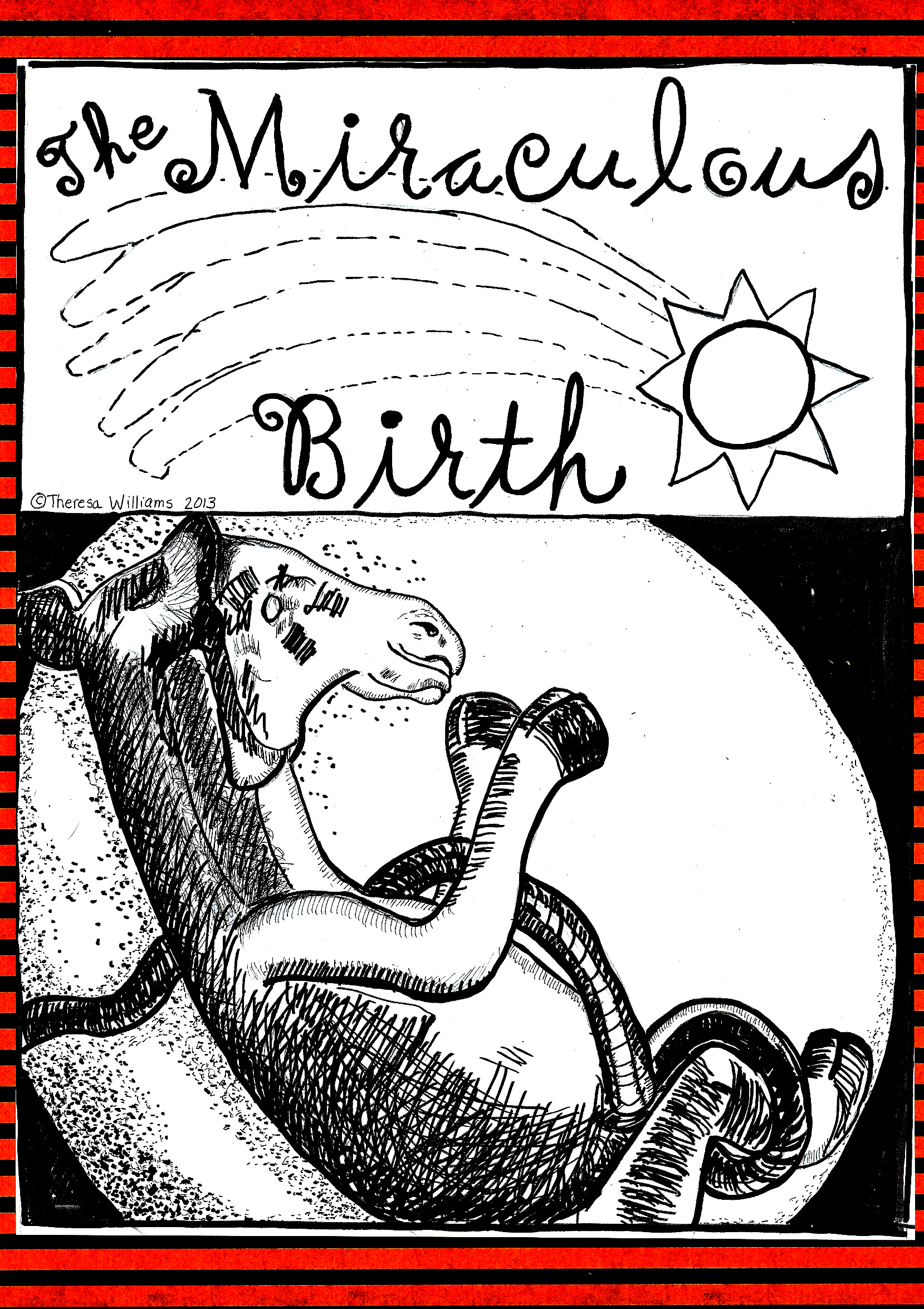

My Goat Child's very form would place him in the world between humans and animals. He would always roam the outskirts, exist somewhere “out there,” beyond social norms and expectations—which is where I’ve always craved to be. I wanted there to be something holy about him, his birth to parallel Christ’s so that he would be recognizable to us as a special being. And his existence would need to have the tracings of urban legend.

• • •

I’m only beginning the process of telling my story through comics. I’m in that halcyon time when the making feels like magic, and I learn something new every day. What I do know is that that in writing about The Goat Child, I’m writing about a threshold experience. I know that by the end of the project—if I’ve done my work properly—I’ll emerge as a new being.

Perhaps, in the end, this is always what drives me to create: the potential for a new birth, the potential for something miraculous to happen in my life.

Be sure to read The Goat Child series by Theresa Williams in Talking Writing:

The Miraculous Birth of The Goat Child

The Goat Child's Dream

Publishing Information

- “Seth on Peanuts: Comics = Poetry + Graphic Design,” Austin Kleon’s blog, September 10, 2007. Excerpted from “Poetry, Design and Comics: An interview with SETH” by Marc Ngui, Carousel Magazine, Spring/Summer 2006.

Art Information

- All art shown is by Theresa Williams and is used by permission.

Theresa Williams is a contributing writer at Talking Writing. Her novel, The Secret of Hurricanes (MacAdam/Cage 2002), was a finalist for the Paterson Fiction Prize. Her short fiction and poems have appeared in a number of magazines, including The Sun, Chattahoochee Review, and Hunger Mountain. Her chapbook The Galaxy to Ourselves was published in 2012 by Finishing Line Press.

Theresa Williams is a contributing writer at Talking Writing. Her novel, The Secret of Hurricanes (MacAdam/Cage 2002), was a finalist for the Paterson Fiction Prize. Her short fiction and poems have appeared in a number of magazines, including The Sun, Chattahoochee Review, and Hunger Mountain. Her chapbook The Galaxy to Ourselves was published in 2012 by Finishing Line Press.