Essay by John Vogel

A TW Vision for Collaborative Art

I try to avoid politics as much as possible, but when I do occasionally dip into that boiling and uncomfortable hot tub, it never goes well. When I watched the second of the 2004 presidential debates between George W. Bush and John Kerry as it aired live on television, I remember thinking, “Wait, am I actually supposed to take this seriously? This is a farce. You know, if there were music behind this, it could be an emcee battle.”

This thought turned into a four-year rabbit hole in which I created the music and video mashup project Battling Green Eye Shades, which I think of as my coming-of-age-as-an-anarchist story. I wrote music for five questions and the closing statements from the aforementioned debate and then spliced them together with audio and video samples. While I was reviewing this single event and then editing it, layering it, and listening for samples to incorporate, the writers who spoke to me most were Noam Chomsky and Howard Zinn, both anarchists.

I don’t know if I’d call myself an anarchist, but I have an anarchist heart. The idea of anarchy is often equated with chaos, but that’s not what it should be taken to mean here. Anarchy as a social structure would be more like loose associations of cooperatives instead of governing bodies and corporations.

There’s a constant tension between leadership and total freedom, and creating within other people’s standards will always be difficult for me. Putting together a magazine—or playing in a band—involves creative collaboration. In order to achieve coherence, however, this type of project also often requires leadership. Sure, in music, free improvisation can generate some pretty great moments, but I’m more drawn to structured strangeness. Now that I’m one of the editorial leaders at Talking Writing, I’ve been thinking a lot about where I’d like this site to go and the ways in which I’d like it to grow and evolve.

Anarchism and leadership aren’t mutually exclusive. Any social structure requires organization to function, but in collectives where leaders emerge, people often don’t recognize the collective work that’s being done underneath the leadership. The whole drive of collective movements is bottom-up, with an intent to accomplish things together to benefit everyone involved. As part of a magazine, I believe editing and collaboration should be communicative and mutually satisfying for the editorial team as well as the writers and artists. Which, luckily, was a quality that appealed to me about TW when I published my first piece.

• • •

One thing I love about the first half of the twentieth century is the open intention to control others. Well, I hate the control part, but I love the antiquated honesty. Besides the blatant use of propaganda and silly advertising, there were Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People, B.F. Skinner, and—my personal favorite—Edward Bernays. There’s a common backdrop to their writings:

Controlling other people is clearly what we want to do. Why wouldn’t we? We’re doing it for their own good. Or at least for our own good. Or to get them to buy things.

Edward Louis Bernays has been called the father of public relations and was a nephew of Sigmund Freud. One of Bernays’s most famous publicity stunts involved creating a fashion trend for the color green in 1934 to sell green-packaged Lucky Strikes. When writing about the genesis of this idea in his 1965 Biography of an Idea: Memoirs of Public Relations Counsel Edward L. Bernays, he put it this way:

Some years before I had asked Alfred Reeves, of the American Automobile Manufacturers Association, how he had developed a market for American automobiles in England, where roads were narrow and curved. “I didn’t try to sell automobiles,” he answered. “I campaigned for wider and straighter roads. The sale of American cars followed.” This was an application of the general principle which I later termed the engineering of consent.

Bernays clearly connected his field of public relations with propaganda and not in any covert, behind-the-scenes way. His book titles include Propaganda (1928), Public Relations (1945), and The Engineering of Consent (1947). In Biography of an Idea, he writes about how, in the service of Vacuum Oil of New York, he mounted a campaign against Pennsylvania motor oil companies that were advertising their oil as natural and therefore better:

I went to Lewis Haney, who was financial columnist for the New York American and head of New York University’s Bureau of Business Research, and we retained the bureau to find out from scientists if oils could be made as good as the natural product. Judgments were confirmatory, and the results were publicized widely. Editor & Publisher attacked what I had done as propaganda, which it was—true propaganda.

These days, it’s rare to hear an expert be so open about manipulation. Of course, people in charge still want to control other people, but they have to be more subtle about it. I may be in charge, but I don’t have any fantasies about controlling anyone. My toddler has already disabused me of that notion.

When Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky wrote Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media in 1988, it seemed to be shrouded in anti-American subversiveness that edged into conspiracy theory. Bernays was alive when it came out, and I feel like they should have had the following conversation:

Herman and Chomsky: The American media functions as a propaganda model.

Bernays: I know! Isn’t it great? I built that shit.

• • •

You can’t really vote for anarchy. There are no anarchist candidates on the ticket.

I advocate for voting, but let’s be honest: for at least the past hundred years, American voter turnout has fluctuated between only about 50 and 60 percent in the presidential elections. You can’t possibly say that voting reflects the desires of the entire country. In cases where the popular vote has been superseded by the electoral vote (such as during my first year voting, in 2000, and Donald Trump’s election in 2016), then only about a quarter of the voting-age population has chosen the president.

As Matt Taibbi points out in Hate Inc.: Why Today’s Media Makes Us Despise One Another, by the time you get to the actual election, all the progressive candidates have been weeded out by what is called “the invisible primary,” a phase of fundraising and political alliance-making that precedes campaign announcements. It essentially creates a feedback loop in which party officials gather behind their preferred candidate and announce to the media those who have received the most donations. That leads to their ascent in polls, which whips back around to create more funding for those candidates. At the end of this phase, Taibbi writes, “[r]eporters tend to describe the winner of the ‘invisible primary’ as more electable and the wiser choice.”

Progressive change has only happened through deep struggle, activism, and unrest—and, even so, the results usually get twisted around somehow.

In other words, American capitalism as it’s practiced today reduces our political power to purchasing choices. I can opt not to purchase anything from Walmart and Amazon, instead buying from small businesses and fair-trade organizations and choosing items that are locally grown or organic. But that doesn’t mean anything will be done by regulators to stop corporations from exploiting people, destroying the environment, and hoarding resources. So when most companies slap “fair trade” or “organic” labels on their products, it’s just another PR move to gain customers. Say hello to Edward Bernays.

Competition is the cornerstone of capitalism, but cooperation is healthier. The constant need to sell things, turn profits, and expand business models leads to shrewdness and deception. In her 2015 collection of speeches, Freedom Is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations of a Movement, Angela Davis stresses the need to transcend the mindset of “individual capitalism” in order to attain a way of life that’s beneficial for everyone.

We need to do this for not only social and political purposes but also artistic purposes. Creating art and connecting through it are deeply human acts that must be preserved and protected. Yet, incorporating them into the capitalistic structure automatically exposes them to a cost-benefit analysis. If you can’t make money from or fashion it into an identifiable product, then it seems like it’s not worth doing. Under capitalism, there’s an implied message that you should either make money and aspire to greatness or fuck off.

Throughout my adult life, my attempts to explain to friends, family, and employers my need to protect the time I spend creating (sometimes at the expense of income, benefits, or paid time off) or my future artistic plans have often been met with incomprehension or suggestions about how to use my artistic drive to generate income. When people decide to do other activities that don’t generate money, such as watching sports, going to church, or playing video games, they don’t receive the same level of scrutiny. The consumer model encourages the elitism of delegating certain people as great creators and everyone else as a customer of that output, as opposed to promoting open, social-based creative endeavors. As a result, the idea of making art because you both enjoy it and think it’s important becomes nonsensical.

I’ve always gravitated toward artistic stances and communities of acceptance. In the introduction of Nick Hornby’s 2006 collection of Believer essays, Housekeeping vs. the Dirt, he describes the ethos of the magazine:

[It] is a broad church, and all sorts of writers (and artists, and filmmakers, and other creative types) are welcome to stand in the pulpit and preach, but it has one commandment: THOU SHALT NOT SLAG ANYONE OFF. As I understand it, the founders of the magazine wanted one place, one tiny corner of the world, in which writers could be sure that they weren’t going to get a kicking; predictably and depressingly, this ambition was mocked mercilessly, mostly by those critics whose children would go hungry if their parents weren’t able to abuse authors whose books they didn’t much like.

And there are even more open, positive environments than the Believer, such as the novel-writing organization NaNoWriMo, which challenges participants to write 50,000 words of a novel during the month of November, and one of its musical offshoots, the RPM Challenge, which invites anyone to write an album during the month of February.

• • •

Then there’s Talking Writing. One of our cornerstones is the editorial process and the presentation of a polished product at the end of the creative experience, so we can’t operate with the complete openness of organizations such as NaNoWriMo or RPM. With our limited resources, we can go through this process only for a small number of the submissions we receive. And yet, throughout the process of bringing out the best in pieces we accept, the tone for which we strive is one of encouragement and positivity.

An atmosphere of negative criticism undercuts an open and motivational environment for creative work. To make art, you need to shut down the fear of embarrassment that you might make something bad. Taste is subjective, so any organization that assumes there are objective qualities of “good” and “bad” in creative work is not a place I want to be. Finding consensus even within a specific niche group can be difficult. There’s no way to avoid talking about likes and dislikes—and that’s the whole point of viewing or listening to art, establishing those preferences—but we need to be aware of their subjectivity.

The authors of the 2021 essay “Scene Preferences, Aesthetic Appeal, and Curiosity: Revisiting the Neurobiology of the Infovore” in Brain, Beauty, and Art run up against this same issue in neuroaesthetics: “Achieving an understanding of the brain basis of how humans get pleasure from visual experiences is made more difficult by the subjective nature of personal taste, which is itself often obscured by strong personal convictions about the universality of our preferences.”

The essays, poems, and artwork that TW publishes will always express the personal tastes of the collective—that’s unavoidable. But we largely work with relatively unknown writers and artists, which speaks to my egalitarian ethos. Every submission that comes in has a chance of making it through, including my own eight years ago. When I submitted my first piece to Talking Writing, we were strangers. When the piece was accepted, that was the first step in a long line of small advances that resulted in my becoming the art director. Such open acceptance, careful consideration, and cultivation of an unknown artist are really hard to find.

I love being sparked by art. It’s one of the best and oldest experiences to which we have access, and when you can achieve that by your own creation, that’s the jackpot.

“To create, and to be brought to one’s knees by creation, that is at the height of being human,” writes Imani Perry in her 2019 book Breathe: A Letter to My Sons. As a society, we need to place a higher value on art in general. And if I can help others find their route to artistic expression—as a musical collaborator, a videographer, art director of Talking Writing—it does my anarchist heart good.

Publishing Information

- Battling Green Eye Shades by John Vogel, Vimeo, January 20, 2009.

- Biography of an Idea: Memoirs of Public Relations Counsel Edward L. Bernays by Edward Bernays, Simon and Schuster, 1965.

- The Century of the Self by Adam Curtis, BBC, 2002.

- Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media by Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky, Pantheon Books, 1988.

- Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media by Mark Achbar and Peter Wintonick, Necessary Illusions Productions, Inc., 1992.

- “National General Election VEP Turnout Rates, 1789-Present,” United States Election Project (website).

- Hate Inc.: Why Today’s Media Makes Us Despise One Another by Matt Taibbi, OR Books, 2019.

- Freedom Is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations of a Movement by Angela Davis, Haymarket Books, 2015.

- NaNoWriMo website.

- RPM Challenge website.

- “Scene Preferences, Aesthetic Appeal, and Curiosity: Revisiting the Neurobiology of the Infovore” by Edward A. Vessel, Xiaomin Yue, and Irving Biederman, Brain, Beauty, and Art, edited by Anjan Chatterjee and Eileen Cardillo, Oxford University Press, 2021.

- Breathe: A Letter to My Sons by Imani Perry, Beacon Press, 2019.

Art Information

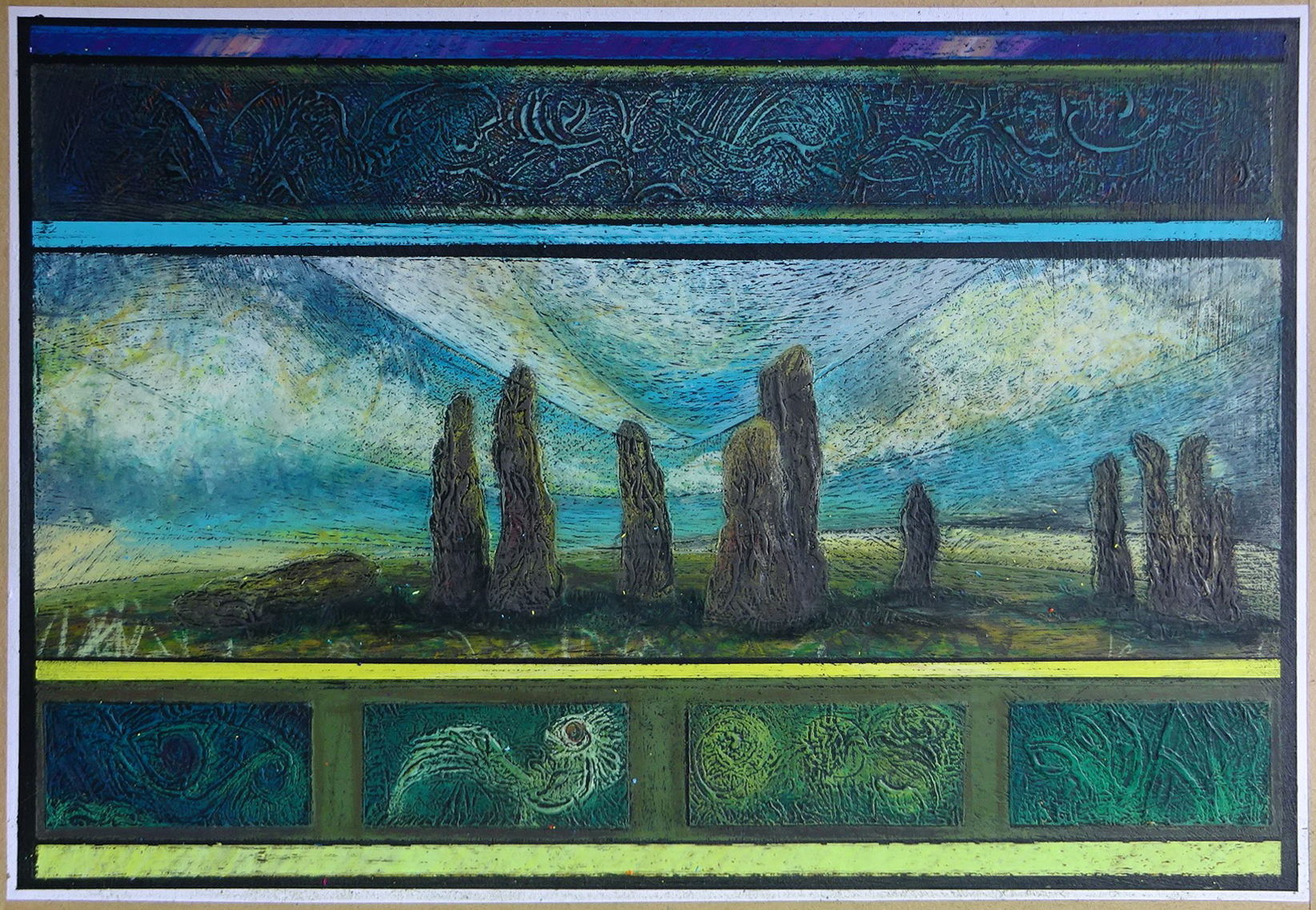

- “The Ayes Have It,” “Gawky Mound,” and “Learning to Walk Backwards” © ‘WART’; used by permission.

John Vogel is a musician and writer in Philadelphia. He is the art director for Talking Writing and creator of the multimedia project Weird Music. Aside from his TW work, he has served as a reviews editor for independent magazines as well as a linguistic annotator and a member of the Philly band Grandchildren. He’s also a stay-at-home dad.

John Vogel is a musician and writer in Philadelphia. He is the art director for Talking Writing and creator of the multimedia project Weird Music. Aside from his TW work, he has served as a reviews editor for independent magazines as well as a linguistic annotator and a member of the Philly band Grandchildren. He’s also a stay-at-home dad.

For more information, visit John Vogel’s Vimeo page and his Eddie Sids Vimeo page.