Essay by Ronald J. Pelias

On Getting It Right

I could say “slippery as a snake,” but snakes aren’t slippery, so more like an eel. But I’ve never touched an eel, and I don’t know if eels are slippery—a quick look online tells me they are, because they produce a mucous covering to help them get through tight spaces and glide through the water, except I don’t like the connotations of mucous. Maybe I should say “slippery as a fish,” because I’ve held fish, like the time I thought I caught a trout but, as I took the hook from its mouth, it slipped right out of my hand back into the water.

The more I think about it, I’m not sure slippery describes what I want to say. It comes and goes as quickly as a hummingbird—it darts in, pauses, letting me have a glimpse, then darts off, leaving me to ask if the glimpse I got is good enough. If I think about it for too long, I’ll wonder if it was ever there, even though sometimes after it’s gone, I’ll hear its hum, as if it is still speaking to me. All this makes me think of Robert Frost’s definition of poetry as a “momentary stay against confusion,” a definition I’ve always liked. It helps me realize that what I’m saying is not very original, even if I link it to hummingbirds.

To tell the truth, I experience it more like a sloth—slow, so slow that I often feel frustrated by my pace, by my inability to find what I want to say, although eventually sloths do get to where they want to be. But I doubt if they are ever frustrated by their pace. I’m never sure after my final period if I’ve found what I wanted, which suggests I should go even slower than a sloth, though that would make it more of a tedious chore.

To tell the truth, I experience it more like a sloth—slow, so slow that I often feel frustrated by my pace, by my inability to find what I want to say, although eventually sloths do get to where they want to be. But I doubt if they are ever frustrated by their pace. I’m never sure after my final period if I’ve found what I wanted, which suggests I should go even slower than a sloth, though that would make it more of a tedious chore.

That reminds me of the steady work of the ox, day after day, pulling the plow, digging up who knows what, creating space for planting, but the ox never sees the harvest, only its remains. It just keeps plodding along, row after row, doing what it is told to do—like finding line after line or sentence after sentence until it’s done, doing what everyone says you should do, one heavy foot or word after another—which, when I’m not careful, means I get stuck in a rut.

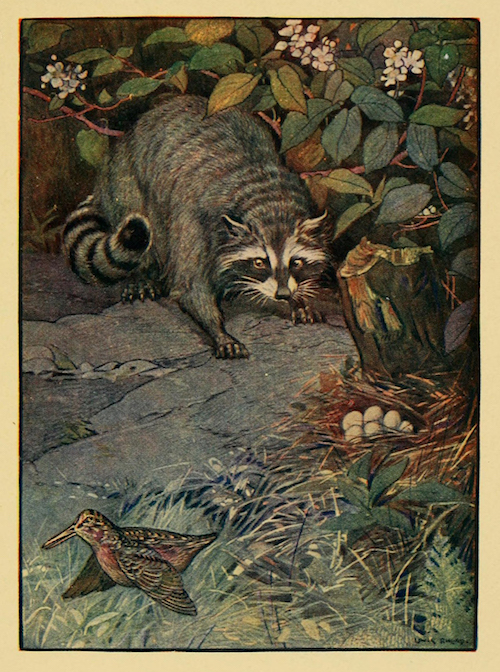

I’d rather be inventive like the raccoon, which nightly goes from garbage can to garbage can to find what it wants, to feed from the waste of human lives. It knows the value in the discarded, knows the drama of the search—although it lives in fear of being caught for taking someone else’s mess and claiming it as its own.

I’d rather be inventive like the raccoon, which nightly goes from garbage can to garbage can to find what it wants, to feed from the waste of human lives. It knows the value in the discarded, knows the drama of the search—although it lives in fear of being caught for taking someone else’s mess and claiming it as its own.

Maybe the words I want are more unpredictable. A dog seems pleasant enough, but before you know it, the dog bites your head off, particularly pit bulls, which you should never let near children because of the damage they might do. Besides, who wants all that barking at the slightest noise or a passing shadow? Everyone knows that barking works best only when there is real danger, and sometimes it’s hard to know when real danger is present.

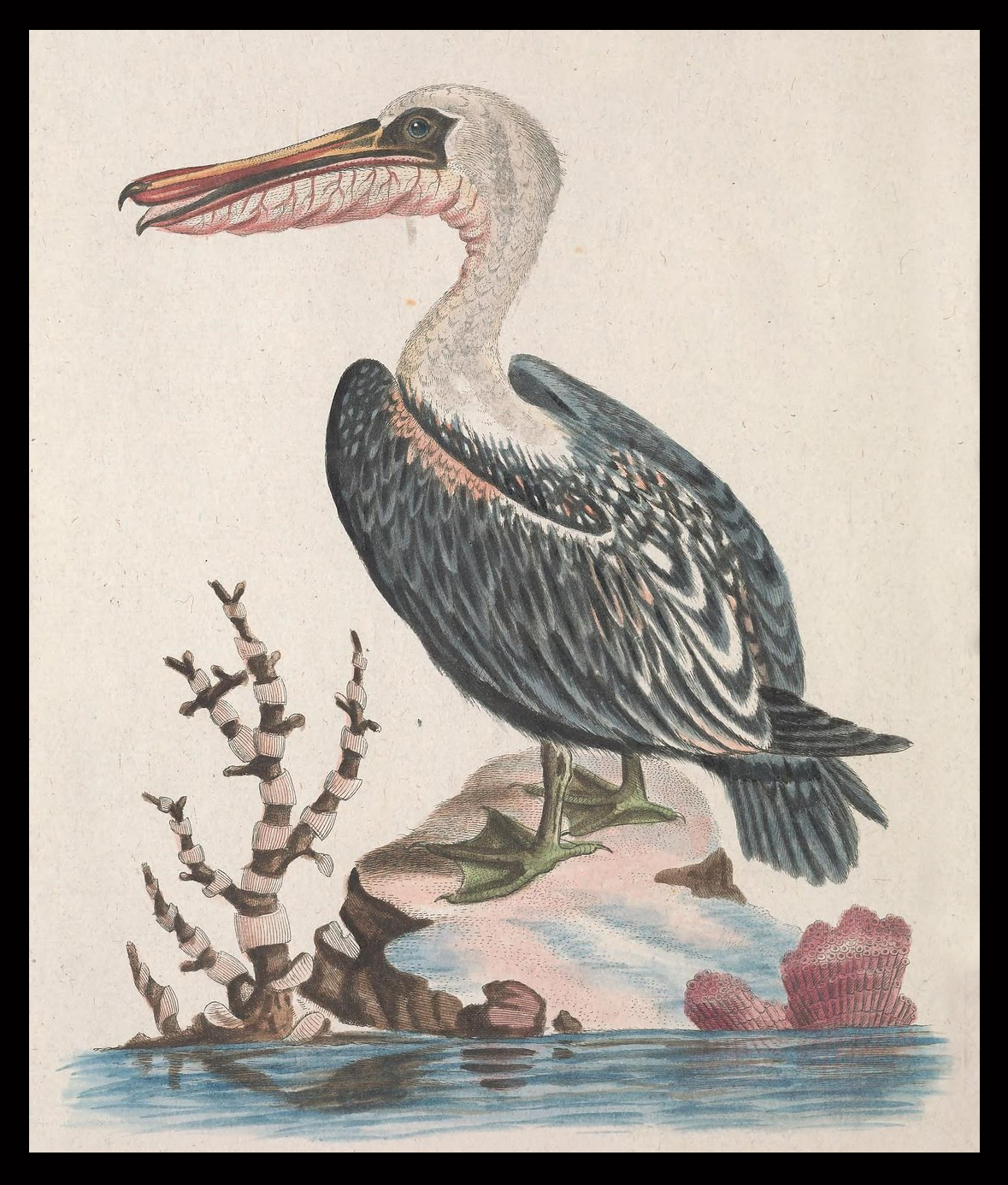

Maybe I should say it’s just "strange" like the pelican, whose “beak holds more than his belican,” as Dixon Lanier Merritt and others have said in the famous limerick. Sometimes by taking in so much, it’s hard to know what’s being chewed, which can confuse me if I don’t think about it carefully enough. I never know what might come out of my mouth or what strange new way I might have to digest things I hear others say.

Maybe I should say it’s just "strange" like the pelican, whose “beak holds more than his belican,” as Dixon Lanier Merritt and others have said in the famous limerick. Sometimes by taking in so much, it’s hard to know what’s being chewed, which can confuse me if I don’t think about it carefully enough. I never know what might come out of my mouth or what strange new way I might have to digest things I hear others say.

All this stuff about chewing and digesting gets me to cows masticating and their multiple stomachs, which I don’t want to bother looking up just to identify what kind of cow would be most apt. I recognize I’m being lazy—not a good quality for anyone trying to get it right—and I have to admit I’m not feeling good about myself.

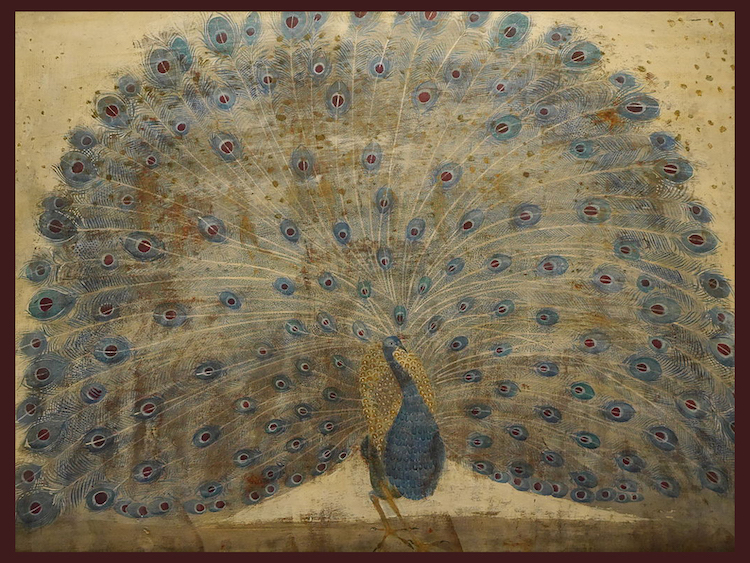

So, I’ll end my menagerie with a peacock. For a bird its size, it moves along in unremarkable ways, until it presents itself with a flourish, insisting on attention because it isn’t ordinary, because it’s worthy of notice, which reminds me of purple, purple prose that Horace warned about centuries ago. I’m at the point of giving up on getting right it, ready to acknowledge it’s too slippery for me, with its yes, that’s it/no it isn’t, with this deadly pace, this slow plodding, digging and digging and finding nothing worthy of a good chew—nothing moving beyond the everyday.

Publishing Information

- “A Gorgeous Bird Is the Pelican, Whose Beak Will Hold More Than His Bellican” by Garson O’Toole, Quote Investigator, June 20, 2020.

Art Information

- “A Congress of Animals” by Francesco Castiglione © Metropolitan Museum of Art; public domain.

- “Sloth” © BibliOdyssey; public domain.

- Drawing of Raccoon © Biodiversity Heritage Library; public domain.

- Drawing of Pelican © Biodiversity Heritage Library; public domain.

- Painting of Peacock © Merab Abramishvili; Creative Commons license.

Ronald J. Pelias has spent most of his career writing books—such as If the Truth Be Told (Sense/Brill Publications, 2016); The Creative Qualitative Researcher (Routledge, 2019); and Lessons on Aging and Dying: A Poetic Autoethnography (Routledge, 2021)—that call on the literary as a research strategy. Now he just lets his writing lead him where it wants to go.

Ronald J. Pelias has spent most of his career writing books—such as If the Truth Be Told (Sense/Brill Publications, 2016); The Creative Qualitative Researcher (Routledge, 2019); and Lessons on Aging and Dying: A Poetic Autoethnography (Routledge, 2021)—that call on the literary as a research strategy. Now he just lets his writing lead him where it wants to go.