Short Story by Troy Farah

Editor’s Note: In “A Curious Animal,” Troy Farah explores the fictional relationship between an abrasive old man, an unidentifiable and energetic tiny primate, and the community surrounding the pair. Farah’s story previously appeared in Spillers #3, an anthology from Four Chambers Press, which has since closed. We are happy to publish it in the TW Reading Series, which brings works previously published in print to the online community of readers.

A Curious Animal

It seemed most likely that Greil had won the curious animal in some sort of subterranean market or gambling ring. It was simian, all fur and teeth, but its form and mass didn’t appear in any volumes we could compare it to.

We never knew for certain its origin, only what we could accumulate from quick glances at it as it darted about. We imagined the thing to have emerged from the foggy, moist reeds on the morass or perhaps from the wood to the south.

It had an alarming amount of energy, almost comical rage—but while it would occasionally knock things over or startle children in its energetic fits, it was never prone to violence. It did not bite, hit, smack, or throw things.

We couldn’t agree amongst ourselves on its name or what it was actually called—it was just It. Greil seemed to have half a dozen or so handles for it, muttering or sometimes barking them out at the thing interchangeably. Terreur, he called it. Bastaard. Dief. Kak-kak. Neuker.

But what he called it most often was Beest.

The tiny primate only came up to Greil’s calf, but its arms could stretch to his nipples. Greil kept it somewhat clean, but we assumed he used a garden hose to jet down its mange. It smelled like the cans of dog food he fed it.

Before owning the small creature, Greil had been sleeping beneath the ticket box he managed at Theatre Oranje. When the small animal began living in the booth with him, it became clear to the theater overseer Beest was having an impact on ticket sales. Greil was told the reason he was fired was for his habit of long, drooling gazes into the bosom of any young female to approach the theater, but he had a tendency to stare this way at everyone.

Greil was a stooped, elderly man who preferred to hide from any direct light and shuffled slowly from cobwebbed corner to corner. He had trouble hearing, and his drooping chin would cause him to snarl when asking someone to speak up. He came across as abrasive, and to say Greil was merely ugly might have been kind. His demeanor might have had more to do with his firing than anything he actually did.

With his job and his home both gone, Greil now only had the anonymous imp that stayed close to his side.

Greil found an old cart from which he sold woodcarvings of various saints and mythological figures. No one ever bought them, it seems, or none survived. The old man would also beg in the shadows outside the cathedral, appearing withered and rigid like a stiff cadaver torn from the bog. But soon enough, he taught the animal a few tricks, much to the delight of tourists and young children. He would laugh and make Beest walk on stilts or smack at a thumb piano, and the coins would tumble into his satchel. He must have made decent income from Beest’s somersaults, but they still slept in the park.

He fed the animal better than himself, sometimes whatever the two could find fishing in the canal, mostly gruel given to him by the local parish soup kitchen. The two were often seen hunched over the same bowl, slurping it up.

“Do you have any idea what that creature is?” the parson asked one of the volunteers. She shook her head no.

“Is it sanitary to keep around?” She shrugged and went back to slopping bowls, but the parson kept his eyes on Beest.

The primate’s arms were lank, often wrapped around the back of its head with the elbows still dragging near its squatting haunches. It was known to leap up suddenly, limbs fully extended, the long, loose seams of flesh beneath its arms then billowing out like some sort of veiny, partially-deflated balloon. In this way, it would routinely bound about, screeching excitedly.

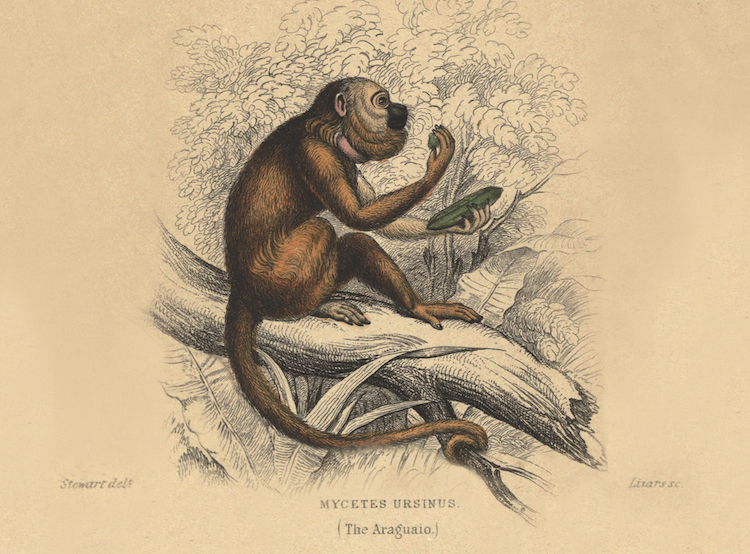

Vague and shimmering, it evaded distinct description—too cat-like for a lemur, too orange-skinned for a grivet, too large for a tarsier—certainly not chimp or anything obvious. Someone showed us a faded illustration plate by some idiotic German naturalist named Schubert. It was of an ursine howler, which we temporarily agreed upon it being, but looked again and couldn’t tell. Its fangs were closer to lynx, its ears bowled like a fennec fox. It was constantly panting, and slobber flitted from its open mouth onto its dry. flaking, calloused feet. We were too naïve to be wary of vaccination, but we avoided touching it all the same.

Unlike Beest’s bulging orange eyes, which rattled in whirls, Greil’s were masked behind the thick-as-bulletproof glasses hugging his face. In contrast to the ape’s darting movements, the elderly man was sluggish, his neck furred with ghostly, prickly patches.

Despite his body odor—something like fermenting onions and burnt tobacco—Greil could make himself invisible. He would hide in corners in pubs and markets, wordlessly soaking in the comings and goings around him with his marble eyes. Upon turning a bend, Greil would startle us with his sudden presence, getting us to yelp helplessly, then, regaining our composure, we would putter off, embarrassed.

Beest would be found breathing heavily at his feet, scooting around in the dust, wearing a collar made of cream-colored aldehyde-tanned ostrich leather. Dangling from the collar was a deep blue sapphire, rumored to belong to a former love of Greil. The collar was attached to a leash wrapped around Greil’s grubby fist, and he would tug at it sharply whenever he wanted Beest to "dance."

Greil’s teeth were endlessly exposed, always vise-gripped around small, thin cigarillos. He taught the ape to smoke, but when this trick failed to produce extra coins from townspeople, Greil abruptly forced Beest to give up the addiction.

Greil would control Beest with a tiny bone flute on a chain necklace, which was effective half the time. If it did not come, he would scold the animal, but we never once witnessed the owner raise his hand against it—not even when it would urinate on him or screech in his ear.

Perhaps Greil wanted the creature inasmuch as they were both orphans. Or perhaps he saw Beest as some sort of guidance animal for his ailing eyesight. The pair resembled lost circus troupers, wanderers without origin, stuck out of time. No one knew where Greil was from, either. It was assumed that his family was lost in the Great War, but this was all we knew.

And this conceivably explains our collective fascination with the curious animal and its owner, even if we largely ignored their presence during the long period they shared our streets. After our little village required rebuilding a second time, we wished to rescue our own history, including the narratives of ghosts in our midst.

Unsurprisingly, Beest eventually chewed through its leash and disappeared. Greil wandered through the streets, wailing for it in all its names. We avoided him with more intention than before, avoided his dribbling eyes, his quavering throat stretching back sobs like a strained dam.

Winter seized us sopping wet, raining pipestems, as we locals say—yet not freezing enough to whiten the troughs of mud and sickly, nude trees scattering the morass. From afar, we witnessed Greil search these marshes for long hours. A pallid vapor hung over the reeds, and a plague of hovering firebugs burst into bloom, but no Beest was recovered.

• • •

One early spring morning, the ground thawed just enough for scattered green shoots, a little primate was spotted from afar by a farm boy, who promptly shot it through the skull.

The farmer claimed the animal had murdered a handful of his chickens, and he produced three or four bloodied pincushions as proof of what was left of the hens. What his son did was practically in self-defense, he argued. But we only ever knew Beest to be harmless, if not startling.

The pelt was passed around for evidence, its mangy coat at first unmistakable, but upon closer inspection we were uncertain, and then convinced it was some other primate. We had no idea who or what this matted fleece could have belonged to. Later, we learned of a nearby travelling carnival that had caught fire due to an accident with a flame juggler. The ringmaster came to us to inquire about a large number of their apes that had gone unaccounted for, and this seemed to explain the fur in question. Most of all, it lacked the distinct collar Beest had been known to wear.

Greil was never seen again to confirm the creature. Months earlier, Greil had been discovered beneath a sheet of ice on a park bench. The police had thawed him out and kept him in custody the rest of the winter for his own good. When he was finally released, he vanished. The last one to see him was the parson, who, upon Greil’s insistence, served him communion instead of gruel.

After only a few days, Greil’s absence in the city was felt by some, including the parson. He led a good majority of the town together for one final search for the creature, and we spread out among the morass. However, it soon grew dark with no sign of the thing, and a leftover late-winter ice storm unexpectedly swept through, sending us scattering back to the city center with little more than mud-caked boots to show for it. We felt vanquished, wiping the sweat and mud from our smeared faces. Somehow, we knew Beest was still unaccounted for, and always would be.

Art Information

- Illustration plate of Ursine Howler © Biodiversity Heritage Library; public domain.

Troy Farah is an independent journalist from southwest California. His reporting on drug policy and science has appeared in Wired, the Guardian, Undark, Discover Magazine, Vice, and more. His fiction has been published in Terraform, Tin House Open Blog, Four Chambers Press, and others.

Troy Farah is an independent journalist from southwest California. His reporting on drug policy and science has appeared in Wired, the Guardian, Undark, Discover Magazine, Vice, and more. His fiction has been published in Terraform, Tin House Open Blog, Four Chambers Press, and others.

Visit Troy Farah’s website or follow him on Twitter @filth_filler.