Theme Essay by Lorraine Berry

Hungry Kids + Low Budget + Proven Bad Cook = Disaster

We were not what you’d call a gourmet family. We were English peasants, and I grew up on a diet of minced meat; meat pie; pie and chips; fish and chips; sole boiled in milk; bubble and squeak; mashed potatoes; boiled potatoes; roasted potatoes; baked beans; the occasional piece of steak-like meat that had been cooked in the oven until it was unrecognizable; eggs, chips, and beans; bloody awful vegetables that could only be eaten if they were mashed into whatever the potato side dish was that night; egg butties; tomato soup; and, if my mum was feeling especially vicious, either corned beef or SPAM on a sandwich.

The only things that made up for the usually bland fare were my mother's desserts. Almond tarts. Jam tarts. Trifle. Dundee Cakes. Cakes upon cakes. Chocolate. More chocolate. Custard. Treacle pudding.

Each night was a battle to see if my brothers and I could clear enough space on our plates to qualify for dessert. If not, the rest of the night would be hell. Too hungry to sleep, we'd dream of cereal in the morning. We'd desperately try to predict when brussels sprouts, minced meat, and boiled potatoes would grace our table again and whether that left us enough time to get invited to someone else's house for dinner.

I never learned to cook.

First, I couldn’t imagine ever wanting to replicate the food that had been on our table when I was growing up. (Although, ironically, I occasionally get hankerings for meat pie, Cornish pasties, and chips—lots of chips.) I also had this lofty idea that when I grew up, I wouldn’t have to cook, because I would be a successful woman with a job outside the house. I didn’t know who would do the cooking—a housekeeper, I suppose—but I was determined that it wasn’t going to be me.

• • •

Everything it seems I like's a little bit sweeter,

a little bit fatter,

a little bit harmful for me.

—"Cigarettes and Chocolate Milk," Rufus Wainwright

By my sophomore year of college at the University of Washington in Seattle, I was living on my own for the first time.

My diet comprised whatever I could afford on the wages I made waiting tables at a coffee house, and whatever was left over from my student loans after I had paid tuition and bought books (and more books, and more books, because that was really my thing).

I remember a multi-month course of living on Pop Tarts (which I loved because my mother had considered them too expensive to have in the house), canned lentil soup, and the occasional Budget Gourmet frozen entree. One night—hungry, tired, and cranky—I dropped the Budget Gourmet as I was pulling it out of the oven. I cried as I saw my hot dinner splat all over the kitchen floor, knowing I would go hungry and would have to clean up the mess before my clean-freak roommate got home.

Life as a college student got a little better when I began to explore the various ethnic foods available in the U-District.

For less than three dollars, I could get a big bowl of authentic Greek lentil soup, sides of pita bread and feta cheese, and a cup of coffee. I loved that and ate it perhaps four times a week. At another Greek restaurant, I lived on spinach and feta omelets, potatoes, and coffee. I could get a huge, cheap burrito at the Mexican stand. I could also nurse a cup of coffee and a croissant all evening at one of the many coffee houses in 1980s Seattle.

Cooking for myself was not cheaper. I had no idea how to prepare anything, so I didn’t know what to shop for. It never occurred to me to buy a cookbook, and I just built into my budget that I’d eat twice a day. Cereal at home, cheap food in the U-District at night.

As I worked my way through college, I also worked my way through waitress jobs at increasingly higher-class restaurants. I went from coffee house to all-night diner to Pioneer Square historic bar to sports bar, which was where I was working when I graduated. Unable to find a job with my liberal arts degree, I continued to climb the ladder of fine dining.

Finally, I hit the jackpot, getting hired as a waitress at a popular, high-priced fish restaurant in Seattle, where I could almost support myself on the tips alone.

Although I was still a disaster in the kitchen, I found myself each night explaining the thirty-plus varieties of fish and shellfish on the menu, even down to their textures, tastes, and best cooking temperatures. Thanks to the “crew chow” meals I received as a benefit of working at the restaurant, I fell in love with Columbia River sturgeon, Ahi tuna, Alaskan halibut and salmon, mahi-mahi, ono—essentially, any fish that had a steak-like texture and tasted like something other than “fishy” fish.

And then I met M.

He was a sous chef at the restaurant, and the two of us were a couple within a week. When we moved in together, he did all the cooking. In fact, there wasn’t any question that he would do all the cooking. As I explained, I didn’t like to cook. And, as he explained after watching me, I couldn’t cook. Not in his kitchen.

We got married, and his being the chef was funny for a while. But, if you’ve ever lived with a chef, you know that the kitchen is chef’s territory. His domain. His kingdom. Over the years, M., who was sweet and kind most of the time except when it came to the kitchen, criticized everything I did in that space of my diminishment: I didn’t know how to chop mushrooms, heat up oil in a pan, fry an egg properly, or even wash dishes.

My responses became rote: “Okay? I was trying to help. But fuck you. Do it yourself.”

• • •

Watch out, you might get what you’re after.

—"Burning Down the House," Talking Heads

After our two daughters came, the troubles in our marriage increased. We'd moved across the country to central New York, where I was a grad student and M. traveled more as responsibilities at his work expanded. I couldn’t even call my parents for help, as they lived three thousand miles away.

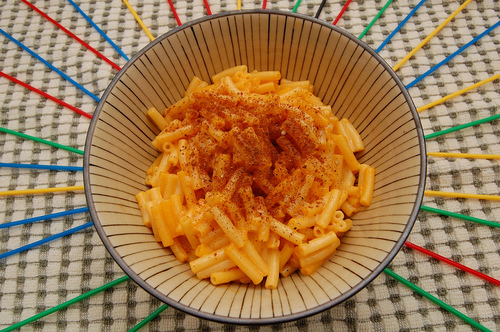

Sometimes, overwhelmed by the idea of picking one girl up from the after-school program and the other from daycare and then going home to make supper, I’d take them to Friendly’s, a hamburger and ice cream chain. But we were on a limited budget, requiring me to attempt cooking at least some of the time. Luckily, the girls—who were adventurous eaters when Dad was home—also loved things like the macaroni and cheese that came in the blue box.

Did I mention the small kitchen fire I started cooking mac 'n' cheese?

M. was away. My daughters sat on the couch, watching SpongeBob Squarepants, while I fixed dinner for the three of us. It was to be “trainwreck,” a dish I'd been taught to cook by an old boyfriend. Trainwreck’s recipe was simple: a box of mac 'n' cheese combined with a can of drained tuna. Mix and serve. Protein and carbohydrates. Add carrot sticks and a glass of milk, and I felt as if I were serving a nutritious meal. And brownies for dessert.

The water had boiled, so, following directions, I dumped the elbows into the pot, turned the gas burner to simmer, set the box down, and went into the living room to check on my kids. I must admit, I loved Spongebob and The Wild Thornberries and could often be lured by “Mom, come sit with us,” as Mrs. Puff tried to teach Spongebob to drive or Eliza spoke to Antarctic penguins.

A piercing sound split our giggles. The smoke alarm. Wait, I thought, how can boiling water set off the smoke alarm?

A cloud of smoke over the stove was my first sign that I hadn’t done something quite right. Apparently, if one places a cardboard box too close to a gas burner, the box goes up in flames. And, as the smoke and ashes climb into the air above the stove, gravity dictates that the smoke wafts over to the smoke alarm. And the ashes? I looked at the slow-boiling elbows. Mt. St. Kraft had dumped its ash on them, and my creamy elbows were now black.

“Who wants to go to Friendly’s?” I asked, as I dropped the pan into the sink and grabbed my car keys.

I had managed to screw up mac ’n’ cheese, which I understand takes a kind of talent in the kitchen that my chef-husband would never possess.

• • •

There was more, more, just inside the door, in the store, in the store.

—"The Corner Grocery Store," Raffi

Leaving their dad was hard on the three of us. My daughters were ten and four, and, even now, going back to that time in my head makes my chest ache. I made mistakes. I was like a panicked bird, flying and flying against a closed windowpane. It's a wonder I didn't break my neck.

For a couple of years, the girls saw my life at its toughest. I was out of work. I didn't have a real home. I camped out on friends' couches or in their spare rooms. For an uncomfortable while, I was back sleeping at our old house. I was in the spare room, while my ex shared our former bedroom with his new love.

Eventually, I found a place of my own and tried to bring my life back to some semblance of normal.

On one of my nights with the kids, I took the youngest with me to her sister’s soccer practice. Afterward, we needed to stop at Wegmans Food Market to get the staples with which I fed them: the infamous blue box stuff, tuna, hamburger, pasta, spaghetti sauce, milk, cereal, desserts, and, of course, anything that they asked for, because how could I say “no” when I felt like such a bad mom?

I had ninety dollars to feed us for two weeks. Because I'd never really learned to cook, I found myself making things like “eggs, beans, and chips”—one of my favorite meals as a kid. I couldn’t make real French fries, of course. I might burn the house down. But I could put frozen chips on a rack and bake them. Sometimes, I combined them with fish sticks. And I bought lots of fresh vegetables that my kids would eat raw: cauliflower, broccoli, snap peas, green beans, carrots.

Do you know how expensive fresh veggies are?

So, that night we were at Wegmans, and it was already after seven. Like their mother, both kids were tired and starving. They had argued in the car all the way to the store, and, afraid of the consequences if I didn’t do something about their hunger, I decided we'd get a cheap dinner at the Wegmans café.

A supermarket café always seems like a good option—until you go to pay for the food. I thought I had it under control: a bottle of chocolate milk for each of them, a kids’ meal for the little one, Chinese food for the older one and me, a bottle of seltzer, and two cookies. But the bill was twenty-seven dollars, and I tried not to panic as I realized that nearly one-third of my grocery money was gone.

I loaded the youngest into the cart, the bottle of chocolate milk in her hand. Up and down the aisles, my daughters sniped at each other. I'd tried to break their bad moods, but it was the end of a long day. Increasingly anxious about the prices of the items I put in my cart, I opted to let them sort it out for themselves. The only thing I insisted was that they use “indoor voices,” since I didn't want them to ruin shopping for everyone else.

Finally, we made it to the checkout line. I turned my back for a second, and the four-year-old knocked over her chocolate milk. Instead of picking it up, the ten-year-old berated her. I walked over, righted the milk bottle, and gave them the evil eye.

"If you’d just picked that up instead of arguing over it, there wouldn't be this much milk on the floor," I said, gritting my teeth. "I'm getting some paper towels to wipe it up, and I don’t want any more trouble."

As I headed for the little service station, I heard the argument start up again.

“That was your fault."

"You made me." "

You're so stupid." "

I hate you."

I don’t allow my children to talk like this to each other and was making a mental note to remind them of that, when a sharp intake of air let me know something big had happened. I turned to see the ten-year-old standing there with chocolate milk dripping down her face, her hair soaked, the front of her white T-shirt turned brown.

"She threw her milk at me!" she screamed.

"It was an accident!" the four-year-old screamed back.

The ten-year-old tried to grab her sister, but she was wearing her smooth-bottomed shoes, the floor was slick with chocolate milk, and, like something from a slapstick comedy, she did a banana-slip and fell on her butt.

They were still in the checkout line.

People in front of them. People behind them.

I stared at the two of them. I found myself thinking, I could turn around and leave. No one would know whose children they were. Eventually someone would call their father, and I would already be in Arizona.

But I lived in a small town. I knew that the faster we got out of there, the less chance we’d run into someone we knew, someone who could report that Lorraine Berry’s kids were ill-behaved and confirm that the woman who'd left her marriage was also a lousy mother.

And, at that moment, I felt like a lousy mother. A lousy cook. A lousy wife. A lousy person.

I wanted to cry. Instead, I began howling with laughter. I couldn’t stop. I was laughing so hard that tears were running down my face, so hard I could feel my stomach cramping up. I grabbed a roll of towels from the service station and nudged my way back in front of the people in line. I didn’t want to make eye contact with them.

But then I found myself apologizing. To everyone. To the people who had been ahead of my kids in line, to the guy at the very back who was checking his watch.

To the clerk, who said, “It’s okay. I’ve seen much worse.”

To the couple behind me, young, smiling, and obviously in love. “It’s okay,” the woman replied. “We were just deciding not to have children.”

“Well, then, my work here is done,” I said.

I wanted to kiss the woman. Instead of berating me for being a bad mom, her smile and sardonic remark re-anchored me to this world. I could stop panicking. I knew what to do. Clean up the mess. Pay for the groceries. Take the kids home, bathe them, read them a bedtime story, and start again tomorrow.

And tomorrow, when I made trainwreck for dinner, I’d remember to move the box away from the burner. See? I was learning how to cook.

Art Information

- “Bubble & Squeak with Bangers” © Darren Pierson; Creative Commons license

- “University District, Seattle” © Curtis Cronn; Creative Commons license

- “Second Dinner” © Matt Mets; Creative Commons license

- “Portland Market Veggies” © Keith Moul; used by permission

Lorraine Berry is a contributing writer at Talking Writing.

Lorraine Berry is a contributing writer at Talking Writing.

She lives with her two daughters, two dogs, and partner, Rob, who, on the night this was written, made pepper-encrusted New York steaks and potatoes in a demi-glace sautéed with onions and a bit of pancetta.