Essay by Steve Henn

Living With My Ex-Wife’s Suicide

Lydia threatened to kill herself so many times in our marriage that it was an interminable refrain. It was an earworm, the chorus to a pop song you hated to hear, because once you hear it in the air, it plays a thousand times in your head.

No. That’s not it. What I tell people in person is what I really think: that she threatened suicide so often it eventually became as common as commenting on the weather. Something like that, mixed up in a deadly emotional cocktail with anxiety and denial. Something like, Gonna rain today. Why don’t I just kill myself?

“If I’m that much of a problem for you, I’ll go ahead and kill myself.”

“I don’t want to live. You’ll be okay without me.”

“Oh yeah? Maybe I will. MAYBE I WILL.”

She talked about it so often—or rather, threatened to go through with it, for we would never discuss particulars—that my response eventually became a burst of anger right back at her.

"Live or die, but don’t use this bullshit to manipulate me."

That was 2008, 2009, 2010. We lived here, in Warsaw, Indiana, in the same house I occupy with three of our four kids now. The oldest is off to college. She was in fifth grade when Lydia and I divorced in 2011. Our communication as “co-parents,” as such divorced couples are sometimes called, from that point on was frequently acrimonious.

Until one night, when Lydia saw it all the way through. It was the last twist of manipulation, the last card she could play. Or so I saw it at the time, angry and lonely and charged with the new parental duty to do alone what I thought she’d help me do.

• • •

When I picked up the kids that day from her apartment, her elaborate goodbye hugs tipped the world to an odd, woozy angle and kept it there until it tilted over with a 2 a.m. phone call from the county coroner. She hugged each child individually, probably more than once each, and said, “I love you” or “Mommy loves you.”

It was August 2013, a couple of weeks into the new school year. We had just decided I would keep the kids during the week and she'd take weekends. I thought she could paint more. I thought it would be really good for her.

Oren was four years old, Luke eight, Frannie almost ten, Zaya almost thirteen. Zaya and Frannie had September birthdays coming up, two days apart. Now I can’t remember what we did that year for their birthdays. Cake without mom, presents without mom. That’s what mattered—that they'd be aware of the absence of their mother on their birthdays, not much more than a month past her death. That it was the first time they’d ever experience their own birthday as something to “get through.”

I knew something was not right by the way Lydia left the kids. I had a sense of foreboding, as I did at fifteen when my dad died of a sudden heart attack, even if I kept telling myself, no, it’s fine, she’s fine, it’s in your head. I was sufficiently worried, however, that I barely drank that evening—a real rarity—and I couldn’t go to sleep when I lay down.

Sometime around midnight, I got the idea to check the iPad, because Zaya basically used my Apple account—and sure enough, there were a series of messages to her mom, all unanswered:

Mom are you ok?

Mom can you get back to me I’m a little worried.

Mom what’s going on?!

Mom goddammit say something!

For all I knew at that point, it had already happened, and I had failed to do a damn thing about it. Maybe I wasn’t as sure, after bringing the kids home for dinner, as I pretend I was in hindsight. But by the time I checked those messages, I knew something was awry.

I waited up. There’s no way sleep would have overtaken me, even though I had to teach in a matter of hours, even though the nanny who helped with the mornings, because I had to be at school before everyone but Zaya, would be there by 7:00 a.m.

The coroner did call and would not break the news over the phone. When he showed up at my house, I asked, “What happened to Lydia?”

They found her dead, he said. Belt around her neck. Later, her mother would inform me that Lydia had also been taking unprescribed pain pills, claiming this information came from the coroner. “I just knew she wouldn’t do that to herself,” her mom, a fervent Christian, earnestly pleaded.

She repeated it: I just knew, just knew she couldn’t do that. She needed to believe in it. I didn’t say anything. I might have mumbled, nothing that could be assimilated into an affirmation. Her mother didn’t know. I knew. I was the one who knew it could happen. I was the one who knew.

• • •

Once my dad died unexpectedly, when I’d just finished my freshman year of high school, I lived for a long time with the fact of death. But that had happened so long ago, I forgot. I didn’t forget that my dad had died, but I forgot, somehow, the reality of death, the inevitability of people I love dying. The trauma of my experiences in Bloomington in the 1990s made my self-pity over my dad seem distant and unmeaningful.

In Bloomington, a good two years before I met Lydia on Halloween night 1999, I was hospitalized, again and again, for various psychological maladies. This led to my own suicide attempt that June. It was a weak attempt. I told my brother what I drank right after I drank it, and he and my mother set the wheels of rescue in motion almost as if they anticipated it—the drive to the ER, the liquid charcoal down my throat, the ungodly pleasant comfort of the weighted blanket on me in the ICU.

If I didn’t know the urge seriously enough to make a thorough attempt, I knew what it felt like to be desperate enough to try it as a way of announcing not knowing what the fuck to do. Perhaps that was what Lydia was telling me when she made threat after threat. Perhaps I was self-centered enough to think only of how this affected me, to assume she wouldn’t actually do it.

Here’s what happened in Bloomington: God hated me. Everyone I knew preferred that I be dead. I was up for days. Didn’t eat for days. Even the watermelon at the local Kroger was poisoned with antifreeze, I was sure of it. The whole fucking town was conspiring against me. Whenever I turned my back, people were pointing and laughing. God, did they hate me.

I lived with that paranoia viscerally before meeting Lydia, and even when it passed, it stayed. Halloween 1999 was one of my first forays into the world of young adult normalcy since leaving Madison Center in South Bend, where they rehabilitated me. Within three months, fatherhood was imminent. We'd created a life. Come September, we'd have to care for that life, we’d have to parent her, we would find out by ultrasound. "I’m going to be an amazing mom," Lydia said. "Just you wait. Just you wait and see."

And now, all four of our kids, at an even younger age than I had to, had been forced to recognize the reality of death. Everyone goes through it sometime, but to go through it via your own mother’s suicide seems an especially damaging introduction.

Some well-meaning person told me—no, I think I read it—that it’s important for the living to see the body of the dead person, to witness the fact of the death. So, convinced this was healthy, I took Oren and Luke and Zaya to see Lydia one last time before they cremated her. The mortician had stuffed towels around her neck so the scars would be obscured.

But Frannie, my second oldest, refused to go, even though I’d urged her to join us. Now, I’m glad she made her own decision on that. It would have been a trauma she wasn’t prepared to go through. Or perhaps the fact of her mother’s death was real to her, as real as it could get, whether or not she ever saw the body.

• • •

Afterward, I drank every time I thought about Lydia, and I thought about her a lot. Every time something resembling a feeling crowded my brain, I’d grab another craft beer, put on another record, turn the volume up. It got to the point where, alone in the living room, I’d play Nirvana: Unplugged and bawl to “Where Did You Sleep Last Night?” Also bawled to Neutral Milk Hotel. Also cried to Daniel Johnston, a favorite of hers.

The drinking got gradually heavier, more compulsive. I stopped referring to myself in jest as “an alcoholic,” because I’d become one. I drank alone; I drank with my friends. More and more, every day.

Frannie started looking at me funny. It was a “what the fuck are you doing to yourself” kind of look. I didn’t like the feeling of shame that came with being looked at by my daughter in that way.

In my first year of sobriety, I began writing it out. Those poems became my chapbook Guilty Prayer. I got sober on January 22, 2017, and put the chapbook together in February 2018. By then, I’d accepted my responsibility for the kids’ well-being as the only surviving parent.

This is nothing that deserves an award or a pat on the back. I know this. It’s not heroism to try to be a reasonable parent for your kids. Early in my sobriety, someone I trusted told me the only way I could possibly make amends for my shitty treatment of Lydia in our separation and divorce was by a living amends, taking care of the kids. She would want you to be a good dad to them, wouldn’t she? my confidante asked. The only honorable handling of the task in front of me was to try to be a good dad, for my kids and for the woman who’d once been my wife.

• • •

Early in my sobriety, I also remembered a conversation with Lydia that I’d managed to suppress. We had the first baby in a stroller and were walking around the wider downtown Warsaw area, talking the way we talked when we were first married, as if we were there to help each other, to see each other through.

“I’m going to kill myself one day,” she said.

I got angry. There we were, with our new baby, and she’s announcing that at some undetermined point in the future she was going to do herself in. Right there, under the shadow of Gordy’s Sub Pub, as if we were talking about a college fund for our child.

“Your family will help you,” she said. “I know they will.” She managed to re-direct the conversation to something inconsequential until I let it go. She didn’t want to debate it. She’d just wanted me to know.

• • •

My sister had a social-worker friend who said there’s a name for constantly threatening suicide. People with Borderline Personality Disorder do that. For attention. To try to get you to see something the way they do.

It just wasn’t real to me. That’s not an excuse; it’s the fact of how I felt. How could anyone want to die so insistently, for so long, putting off the attempt for years? It didn’t feel like she was putting it off. But I guess it wasn’t just a negotiating tactic.

I could have done something. We could’ve gotten counseling or avoided our respective affairs with drugs and alcohol or replaced that feeling by making art, holding onto, for dear life, my poems, her painting and drawing. Or I could have paid for her to go to my psychiatrist, who helped me descend from the mountain of stress our relationship became when we were divorcing. I could have admitted she needed a good psychiatrist, too, could’ve done something to get her the competent care I was getting.

Instead, I drank and drank. I yelled at her. I sent rude and often profane text messages. I got fed up; I wouldn’t hear it. When she called me and begged me to take her away from outside a drug house in the country, I went, waiting for her histrionic behavior to end so I could drop her at her own apartment building. The goal on that occasion was to deliver her where she needed to be with the least amount of personal involvement possible. Here’s your apartment. Sorry about your life. Not my fault. I’m no longer married to you.

I didn’t do anything. I didn’t get in contact with her after picking up the kids that night. I didn’t call the police or some other kind of first responder when I thought this might be happening. I prayed spitefully: Your move, God. I’m done.

This will be the source of my deepest feelings of regret about Lydia for the rest of my life. In sobriety, we’re told to “let go and let God.” Though I was still a drunk at the time, that’s exactly what I did.

I can go back to it in my head, but I can’t relive it. It’s hard to see my lack of effort on Lydia’s behalf that night as anything but a forfeiting of whatever influence I could have had over the outcome. This is where the pain comes from. I don’t think it will ever not trouble me.

I don’t feel responsible for her decision, and yet I do. Somehow, I blocked out that conversation on Buffalo Street in 2001 with the stroller—my way of accepting it was to deny it. We had more kids. I probably thought it was past, fleeting—we had two, three kids, then she got hospitalized, then we had another. It didn’t occur to me that someone who so eagerly loved being pregnant would carry that other feeling around with her, as if it were a different kind of offspring, waiting to be born.

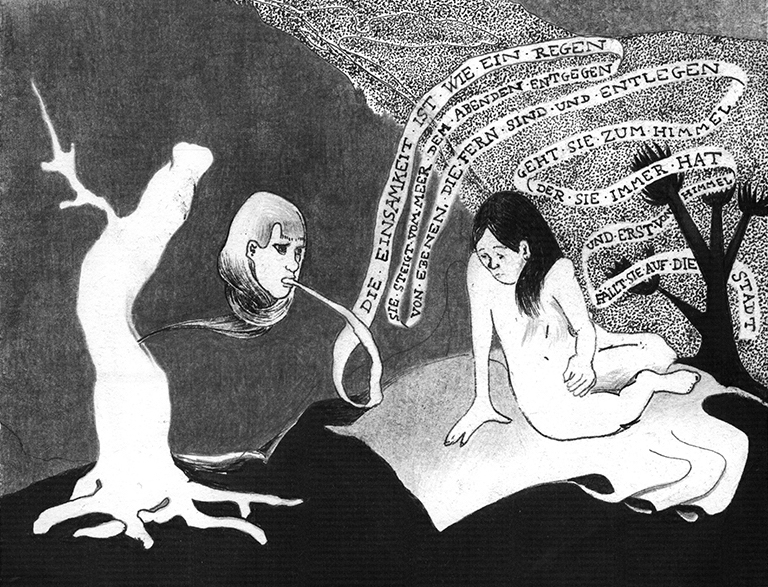

Art Information

- “Tu n'es pas un Intellectuel,” “Einsamkeit (after R.M. Rilke)” (detail) and “Corpus Vacuus Est” © Piotr Szymon Mańczak; used by permission.

Steve Henn wrote Indiana Noble Sad Man of the Year (Wolfson, 2017) and two previous poetry collections published by NYQ Books. He’s been a featured poetry reader from Long Beach to Pittsburgh, Chicago and Milwaukee to Missouri, and all over Indiana. He teaches high school. He continues to work on a collection of essays he’s calling a “memoir collage.”

Steve Henn wrote Indiana Noble Sad Man of the Year (Wolfson, 2017) and two previous poetry collections published by NYQ Books. He’s been a featured poetry reader from Long Beach to Pittsburgh, Chicago and Milwaukee to Missouri, and all over Indiana. He teaches high school. He continues to work on a collection of essays he’s calling a “memoir collage.”