TW Column by Judith A. Ross

A Mother's X-Ray, Google Maps, and the Legacy of Apartheid

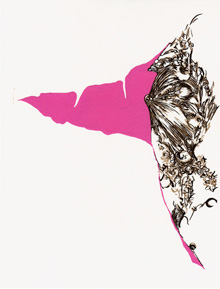

I first saw Sophia Ainslie’s work this spring, when I wandered into Boston’s Kingston Gallery and Ainslie’s “Inside Out” exhibition. Her sharply defined white spaces and odd puddles of color pulled me into an intriguing new world. I knew I had to meet the artist.

Fortunately, her studio is located in nearby Somerville, Massachusetts. It’s one of dozens housed inside a former factory that spans an entire block. Ainslie, our featured artist in this issue, met me outside the brick building a few weeks after my gallery visit.

She led me through a labyrinth of corridors to the cobalt-blue door that opened into her windowless workspace. Its walls were covered with finished paintings and works in progress. West African music played on a boom box.

Although her work packs a big punch, Ainslie is small. Her lively brown eyes look out from under a voluminous mop of dark hair.

I’m not sure what I expected of an artist who mixes an X-ray of her mother’s abdomen with Google maps from her hometown of Johannesburg. But once we started talking, it was clear we had more in common than art.

Like me, Ainslie had watched her mother die of cancer, although she experienced this as an adult. (I was just a teen when my own mother passed away.) And while Ainslie grew up pushing the boundaries of apartheid from the inside, I walked numerous anti-apartheid picket lines in Cambridge and Boston during the 1980s and 1990s.

In her crisp, accented English, Ainslie, who is in her early forties, told me about her life in South Africa as a child. Her family spoke English only. Her parents considered Afrikaans the language of the oppressor, although Ainslie says that she had to learn enough of it to pass her school exams.

She also differed from many of her white peers because throughout her childhood and teens, her parents ran an art school out of their home—a school that was open to people of all colors. That meant it was illegal and often under police surveillance.

The omnipresent sense of being watched likely informed Ainslie’s later creative work—how could it not?—but as a young child, she says, she was unaware that anything strange was going on: “You feel like it’s the norm. Because my parents took care of everything, we felt very secure.”

Although her parents made a point of discussing apartheid every night at dinner to educate their children, Ainslie notes that its injustices remained abstract until she began leaving the house with their black housekeeper’s son, Henri, whom she’d been raised to think of as family.

The two of them were often barred from boarding city buses or were thrown off. When she took Henri to school to perform in a play she’d written, introducing him as her younger brother, her classmates peppered her with questions.

“The kids asked me, ‘Is he really your brother? Does he eat at the same table as you? Does he use the same cutlery?’” she recalls ruefully. “I didn’t understand where those questions were coming from. Why wouldn’t he?”

Looking back, Ainslie says she appreciates how extraordinary her parents’ actions were. “I didn’t know anyone else in the same situation at all,” she adds.

Now a lecturer at Boston’s Northeastern University and New England School of Art and Design, Ainslie remembers her art school home as a lively place to grow up. She participated in adult classes, and comments that “the house was always filled with people: students, writers, poets, musicians, lawyers.”

Her mother, Fieke, also took in people in need. “She loved human beings, and she felt everyone should be treated in a particular way,” says Ainslie. “So if someone was dirty, hadn’t eaten, or was homeless, she would put them in the bath, feed them, clothe them, give them a bed. She made sure they were safe.”

In December 2008, Fieke’s final X-ray—one of several taken since her initial cancer diagnosis in 2005—triggered the idea for Ainslie’s current work. Ainslie says that the delicacy and layering of the image resonated.

“I was just astounded,” she recalls. “I’d never seen that part of the body before. It looks so much like a drawing.”

Ainslie was with her mother when that final X-ray was made. When she told Fieke she was going to make a portrait of her “from the inside,” her mother laughed: “She told the doctor that I was a typical artist, always seeing source material in everything.”

The colors used in Ainslie’s Fragment series come from her mother’s clothes and jewelry, the interior of her house, even its surrounding landscape. Although Ainslie calls these “portraits,” each element has been highly abstracted so “they can take on a new life,” she explains. The hard edges between the white spaces, colored pools, and ink markings are meant to create areas that retain their own identities yet also coexist with the others.

“I wonder if that harkens back to the segregation of South Africa in some way,” she says. “These things always live inside us.”

Fieke died in February 2009, before Ainslie created her “inside” portraits, but she continues to influence her daughter’s art. Ainslie is now working on a piece that contains a pattern taken from one of her mother’s caftans.

The Fragment paintings in her recent exhibition are a radical departure from Ainslie’s earlier works, which include enormous, sprawling wall murals and sculptures made with mixed media and recycled detergent bottles. Those early pieces are a commentary on American consumerism—something Ainslie claims doesn’t yet exist in South Africa.

“Coming here and seeing that wastefulness was quite shocking,” she says.

Our shocking habits may have fascinated her when she first arrived more than a decade ago, but in 2007, after her mother’s cancer went out of remission, the strain of knowing their time together was limited forced her to shift focus.

She began to edit, simplify, and work on a smaller scale—an approach that has yielded a new delicacy of feeling that strongly resonates with me. The recently completed portraits imply a level of mother-daughter intimacy that I’ve never experienced but will always long for.

She began to edit, simplify, and work on a smaller scale—an approach that has yielded a new delicacy of feeling that strongly resonates with me. The recently completed portraits imply a level of mother-daughter intimacy that I’ve never experienced but will always long for.

Ainslie also notes that the Flashe Vinyl paint, acrylic paints, and polypropylene surface she currently works with are less forgiving than the media she used before. “In my past work, accident was an important part of the process. It was about building up history. Here it’s all about specificity and deliberation,” she says.

It’s a bit like life, Ainslie adds: “If the mark happens to be in the wrong place—whatever that may mean—then you’ve got to run with it and make it right.”

To learn more, visit Sophia Ainslie’s website.

Judith A. Ross is a contributing writer and columnist at Talking Writing.

While Judith wishes she’d had more time to get to know her mother as a person, her mom’s sense of justice, love of laughter, and chic sense of style inspire her every day.