Essay by Steven Lewis

Or How I Learned Not to Fall Asleep

In 1967, assigned Swann’s Way in an undergraduate lit class at the University of Wisconsin, I lost consciousness somewhere on page two. This despite being sober and sitting upright on a hard chair in the library. That night, I dozed off again trying to read it in my apartment. Same two pages. I made it to page four the following day on the Rathskeller terrace off Lake Mendota, before my girlfriend found me head down on the table, drool dribbling out the side of my mouth.

A few days later, when I couldn’t get past page four without crashing into a coma, I bought Cliff’s Notes. Fortunately, and unfortunately, that’s all I needed to get through the class.

Attempting to read Proust in graduate school was frankly another series of snoozes. But by then, I’d gotten rather skilled at gleaning enough information from plot summaries and critical abstracts to sound intelligent (enough) in seminars, despite my shameful ignorance.

As Billy Pilgrim explained—I did read Slaughterhouse-Five—so it goes. And so it went onward to my closeted Proust failures as a young instructor at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. At first, while anxiously aware that I was a fraud posing as a learned English Department someone, I slinked around Mitchell Hall hoping no one would ask me a question about Swann’s Way (or, for that matter, Finnegans Wake; The Life and Opinions of Tristam Shandy, Gentleman; The Mill on the Floss; Eugene Onegin; Oblomov; most of The Canterbury Tales, the middle four or five hundred pages of Ulysses; the parts I skimmed in Moby-Dick—ad sominus).

To hide the gaping holes in my literary resume, I effectively adopted the de rigueur academic “knowing nod” at faculty meetings and cocktail parties whenever Proust or some other unread famous writer’s name came up. And again, fortunately and unfortunately, that knowing nod served me rather well over the next decades as a moderately successful, immoderately unsuccessful freelance writer as well as a mentor at SUNY-Empire State College.

Eventually—I’m talking years and years down the academic highway—I was still employed and effectively employing the knowing nod, but with increasingly less fear-of-exposure hidden behind it. All was well, I thought, or well enough.

Then John G. walked into a writing workshop I was offering at Sarah Lawrence College. Beyond quickly recognizing John as a remarkable writer with a haunting voice, I soon learned through his timeless memoir that as a troubled young man desperately in search of love back in the early 1980s, he had read all seven volumes of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time (also known as Remembrance of Things Past).

Like some form of academic PTSD instantly erupting with the jolt of an acid trip flashback in my aging psyche, I felt renewed shame at the fraud I’d been perpetrating for decades. It was time to be an adult, to jack up my eyelids, to force myself to actually read the soporific Proust.

I found my dusty, yellowed, unread copy of Swann’s Way on the attic bookshelf, propped myself up in bed and…two pages later, fell asleep. The next night, I failed again while sitting in a wing chair in the living room, an untouched glass of wine by my side. Then again in my office at Empire State College. The opening lines, from the classic Moncrieff translation, even go like this: “For a long time I used to go to bed early. Sometimes, when I had put out my candle, my eyes would close so quickly that I had not even time to say ‘I'm going to sleep.’”

Swann’s Way was simply impassable. Even Proust said so.

With all options—and my self-esteem—in danger of being lost to Hypnos, I figured my last best hope was to load the damn book onto my iPad and take it to Ignite Fitness, my local gym. I had to be there every other day anyway, and there was little chance I’d nod off and tumble from a stationary bike. (And if I did fall off and crack my skull, so what? I probably deserved it.)

A day later, I hoisted myself up on the bicycle seat, placed the iPad on the bookstand over the handlebars, and—of course, you’re already a few pedals ahead of me—look, Ma, no hands!—I not only got past page two on my first Tour de Nowhere, but didn’t once wobble as I pedaled and read and pedaled and read and pedaled and pedaled and read and read…35 cardiac-enriching pages over the course of the next 45 minutes. Alléluia!

Suddenly, reading Proust wasn’t tedious or boring or sleep-inducing. Suddenly, the opening passage that so ironically begins in bed now demanded my attention:

For a long time I used to go to bed early. Sometimes, when I had put out my candle, my eyes would close so quickly that I had not even time to say ‘I'm going to sleep.’ And half an hour later the thought that it was time to go to sleep would awaken me; I would try to put away the book which, I imagined, was still in my hands, and to blow out the light; I had been thinking all the time, while I was asleep, of what I had just been reading, but my thoughts had run into a channel of their own, until I myself seemed actually to have become the subject of my book: a church, a quartet, the rivalry between François I and Charles V.

And a few pages later, incapable of veering off that channel, the tone and cadence of the narrative voice taking my breath away, I was infatuated, drawn body and soul into the realm of yearning:

My sole consolation when I went upstairs for the night was that Mamma would come in and kiss me after I was in bed. But this good night lasted for so short a time: she went down again so soon that the moment in which I heard her climb the stairs, and then caught the sound of her garden dress of blue muslin, from which hung little tassels of plaited straw, rustling along the double-doored corridor, was for me a moment of the keenest sorrow.

Those were the same words I’d read countless times before. The same sentences that had put me to sleep. And yet, some alchemy had occurred. Something akin to falling in love, to finding some transcendent connection in the universe where there had been only darkness. There was no logic to it, nor was there a way to deconstruct Proust’s sui generis prose in order to discover why I was so swept away.

By the time I reached the evocative passage many pages later about asparagus, of all things, I was as enraptured as the narrator by its “iridescence that was not of this world” and “that precious quality which I should recognize again when, all night long after a dinner at which I had partaken of them, they played (lyrical and coarse in their jesting like one of Shakespeare’s fairies) at transforming my chamber pot into a vase of aromatic perfume.”

And just like that, my smelly gym was filled with aromatic perfume.

I finished Swann’s Way two weeks later with an exultant high-speed spin-class flourish. Proust thus “conquered”—or at least the first of those seven volumes—I went on to read and enjoy several more previously unreadable books while biking to nowhere at Ignite Fitness. I successfully harpooned all of Moby-Dick (including the tedious ship-building passages and the endless ruminations on the color white). Next I read Ford Madox Ford’s The Good Soldier, followed by Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain.

Then one afternoon, not yet ready to begin battle with Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin, I was back at the gym without an unread Great Book to read. And as I pedaled and pedaled, I found myself pondering what metaphysical forces had enabled me to not only overcome my selective literary somnolence but to enjoy what had been such mind-numbing labor.

Legs pumping, mind wandering, here-there-everywhere, I eventually recalled how my youngest son Bay, who is dyslexic, learned his numbers and letters as a young child through gross motor actions—air writing. And moments later, soaring down an unnamed cardio hill, I thought about how our baby girl Elizabeth had spent her first three-and-a-half years of life in various harnesses and body casts and braces, the consequence of severe congenital hip dysplasia. Because she’d by necessity skipped over the crawling stages of toddlerhood and began to walk while still in her brace, Elizabeth’s physical therapist advised us to encourage her to go backward, developmentally speaking, and crawl. The therapist explained that crawling is important in making the neurological connections necessary to develop effective communication between all motor areas and higher learning centers in the brain. So we crawled.

Was it possible that I couldn’t read Proust until I did the equivalent of crawling? Did I need to pump my legs in order to stimulate those parts of my brain required to hear the music of the writing? Was it necessary to have sweat pouring out of my forehead to see the powerful subtext behind the words? I’d become accustomed to doing this kind of intellectual work while sitting still, but maybe I had to actively engage my body to relearn how to read.

That evening after dinner, I sat down on the living room couch, booted up my laptop, Googled “movement and learning,” then “gross motor skills and learning to read”—and promptly fell asleep. Of course.

Two days later, I was back at the gym, pumping my legs, climbing Mount Nowhere, feeling the burn, and considering a little light neuropsychology before pedaling into Eugene Onegin. But as sweat began to bead on my forehead, the hills and valleys brought me to some transcendent geo-meta-physical understanding that I had no interest in wasting my exercise time biking through technical works. I planned to be far too busy traveling along previously undiscovered literary highways where “remembrance of a particular form is but regret for a particular moment; and houses, roads, avenues are as fugitive, alas, as the years.”

Publishing Information

- All Proust quotes are from Swann’s Way, Remembrance of Things Past, Volume One by Marcel Proust, translated by C.K. Scott Moncrieff (Henry Holt, 1922).

Art Information

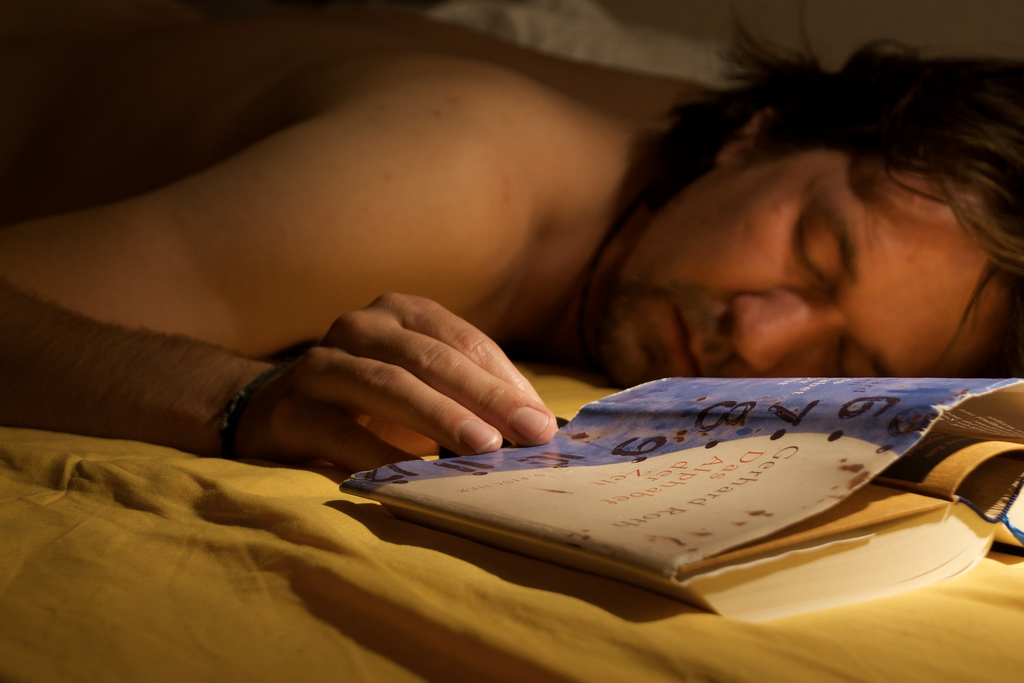

- "What I'm Reading Currently" © Oliver; Creative Commons license.

Steven Lewis is a columnist at Talking Writing, Literary Ombudsman for read650.com, a former mentor at Empire State College, a current member of the Sarah Lawrence College Writing Institute faculty, and a longtime freelancer. His work has been published widely, from the notable to obscure, including in the New York Times, Washington Post, Christian Science Monitor, Los Angeles Times, Ploughshares, Narratively, and Spirituality and Health.

Steven Lewis is a columnist at Talking Writing, Literary Ombudsman for read650.com, a former mentor at Empire State College, a current member of the Sarah Lawrence College Writing Institute faculty, and a longtime freelancer. His work has been published widely, from the notable to obscure, including in the New York Times, Washington Post, Christian Science Monitor, Los Angeles Times, Ploughshares, Narratively, and Spirituality and Health.

His books include Zen and the Art of Fatherhood; Fear and Loathing of Boca Raton; If I Die Before You Wake (poetry); a novel, Take This; a generational sequel, Loving Violet; and A Hard Rain (forthcoming from Codhill Press in December 2018).