Personal Essay by Sara Hubbs

The Advice Post-Partum Mothers Never Hear

If there is no sleep, then there is no time, and there is no need for sleep training.

This is not a manifesto about co-sleeping. This is about bedtime rituals that don’t amount to anything. This is about a bed that was never slept in, about a bassinet I kept next to my bed with my baby in it. This is about a distance that grew between my body and my bed—a space of broken energy between mother and child.

Late in December 2011, we brought our daughter home from the neonatal intensive care unit, a week after she’d been born unable to breathe on her own and had to be resuscitated. I read and reread the warning label on the bassinet in case I missed something. It was her first night home, and I stayed with her alone, as I had many nights before while my husband, an emergency physician, worked the overnight shift.

But something held me down, heaviness and stillness on the chest, her chest, this night and many nights that followed. It was Christmas Eve in New York City, my family had all gone home to Arizona, our friends were out of town, and it felt like the eve of another disaster, another morning after, the night the heat went out.

It was freezing outside. I was already afraid to look in the bassinet. I prepared myself for a frozen little body.

I was always worried that someone was going to take her from me, and that morning I couldn’t remember how I fed her. Did I feed her? I must have slept, but I only know about the things I did instead of sleep.

My nights were wet. There were bowls of cereal eaten in the dark at the window. There was post-partum blood between my legs and night sweats that left me cold, because winter blankets hurt my skin. There was milk that leaked from rogue breasts and tears siphoned from a dehydrated body.

Notice the worry about food, as if it would disappear. I planned my life around it. There was also an obsession with breast milk, because I feared I wouldn’t be able to feed my daughter, as if I didn’t know how. One night at two o’clock in the morning, I found myself on the floor, crying next to spilled milk. When I took the shields from my breasts, the clear plastic tubing swept the three-ounce container to the floor. I hated myself.

I tracked her feedings for over three months in a little green notebook, a mom’s log, positioned next to the glider. Those were the days of tracking that turned into nights of devotional watching, where ceilings turn into lines, and the lines all led to the floor.

I advise you, please, to clean every speck of dust and bundle of hair from your floors. This is a preventive measure to safeguard against certain cleaning obsessions. I preferred sweeping to holding my baby.

Lean in and look under your radiator.

Also, avoid singing “Baa, Baa, Black Sheep” to your child. It is a song with a motive. It implants itself in your brain and is programmed to turn on as soon as you rest against a soft surface or close your eyes.

Try not to listen to your breast pump; they have been known to mock new mothers. In the quiet cold of late December, the pump will chant/wheeze, you suck, you suck, you suck every time the phalanges extrude your nipples to take the liquid that contains your baby’s immunity.

Maybe I’m the only one who heard this, the only one who played the record backward.

• • •

Two-and-a-half years after her birth, we moved home to Tucson. We looked for a house to make into a home in a perfectly fine neighborhood on a well-kept street. As we pulled out of the driveway, our realtor told us about a little girl who went missing on the well-kept street. She was reportedly taken from her family via her bedroom window.

I’ll tell you a secret. Four years after the birth, our daughter still sleeps in our room. We share a nightlight. She, too, has a bedroom with a window, which I just couldn’t and cannot trust.

Listen, this is not an endorsement of helicopter parenting, nor is it an endorsement of attachment parenting. This isn’t a treatise against them, either.

Do you want to know another secret? If you don’t have a picture of your baby after your birth, you can post a picture of your placenta on Facebook. I find this refreshing.

There is a colony for people like us, a colony of IVs, large needles in spines, baby CPAPs, and little white pills. Little pills that work better than safe words and breastfeeding support groups.

I went to a mom’s meet-up once in New York. There were many reasons to be nervous, mainly because I didn’t have my “Brest Friend” feeding-device-pillow-strap-thing. What if I don’t get a good latch? Everyone will know I don’t know what I’m doing. I reached into my bag and touched and retouched the emergency bottle of dry formula I carried with me. I positioned myself near a Boppy (better than nothing) in the corner where I barely touched my baby, where I stared at the carpet and hyperventilated. I drowned in the sounds of other moms, wiping tears from my eyes. The vibrations of the room made my body hurt. It was humming, and I needed, I needed to leave. I felt so bad for my daughter.

I need to ask you, have you ever wanted to be the floor? Not just lie on the floor, but also be the rich brown grain of a good hardwood?

Have you ever been suspicious of Skype? I knew there was something weird about my family, about the way their faces looked out at me from the screen. Their silence I took as blame. They wanted to take her from me, too, and at that point, I wouldn’t have put up a fight.

This one is delicate. Have you ever recoiled from your own newborn?

Don’t leave me alone, I begged. These are the things that occurred to me after the birth: I couldn’t stand in front of the hospital where I birthed our daughter, and I couldn’t even get off at the same subway stop. Invisibility can be protective.

Now, I can’t enter a hospital without an intense feeling of being jailed, of disaster mode, of a need to drive or run fast or scream loudly. I need to scrutinize everyone, monitor actions and words.

It’s also occurred to me that well-meaning people, the pediatrician, the friends who post parenting articles on Facebook, the family who repeat wives’ tales, folk remedies, family birth lore, cannot help us. Mother, we are designed to fall through the cracks, because everyone knows what’s wrong with you, because nobody knows what’s wrong with you. The birth experience is designed for trauma.

The NICU is not designed for families or breastfeeding.

• • •

When I was down on our beautiful hardwood floor, when I was stuffing my face with two egg-and-cheese croissants, listening to my neighbor’s baby being sleep trained just beyond my wall—my own sleep prevented by nursery rhymes, by dreams that felt like gasps for air—I told my birth story to anyone who would listen like an itch that needed to be scratched.

I told of all 36 hours of induction, all manner of disparaging comments, coercion, of disempowerment. I told of all the ways I was kept from my baby, of all the artificial obstacles to motherhood, until I hated the sound of my own voice. Until I disconnected from the telling, until it became superstition, as if I would compromise my daughter’s future state of aliveness by speaking the words born dead.

Now, I can only mouth them.

Did this happen? What happened? Was it as bad as it feels? I knew I was to blame. I lacked confidence. I was scared, and my daughter knew it. That’s why she had hiccups inside my belly.

One night before her birth, she came to me in a dream. I could see her face clearly. Is the door open? She asked. Yes, I tentatively replied.

People said I should have had a C-section. Who wants to push a baby out of her vagina anyway? People told me that at least my baby is okay. My aunt told me four weeks after the birth, “It’s time to get over it. She’s alive.”

As I write this, in 2015, it is four years after the birth. Don’t think for a minute I’m not thankful she’s alive, that I’m ignorant of the fact that there are people who have it worse. It’s just that when feelings in my body come from nowhere, these supposedly baseless fears I feel are true, they don’t come with a sliding scale for pain.

There is a place where mothers like you and me go. It’s a place with a curtain, with a bloody handprint hastily swept across the fibers, a curtain between the labor bed and your child’s warming bed. The warming bed turned resuscitation bed. It’s a place with spotty warm lights and blue babies that plop out of your body. It’s a place with chest compressions and miniature laryngoscopes.

Don’t worry, there’s no skin-to-skin contact in this story; nor is there a cord that pulses to completion. This is about waiting to see if you’ll be a mom, and when you realize you are, the complete difficulty of locating yourself in any of it.

Did you know that becoming a mother could come from somewhere behind you or beneath you or in spite of you? Did you know that neither the self you knew before nor the self that comes after actually exists?

There are just starts and stops.

• • •

Three years to the day of my daughter’s birth, she saw the first picture ever taken of her—her face obscured by a breathing apparatus, IVs in her hands and feet wrapped with tape, steadied by a board. She asked me what happened to her, and I told her how hard I worked to get her out.

On my daughter’s third birthday, I still dreamed of the birth, although the dreams weren’t as frequent anymore. I still startled and felt a tingling sensation radiating from the center of my body when I heard a car honk. I still laid my hand on her chest every night before I went to bed, kissed her forehead—just in case. I still lay in bed, listening to the sound of her breath until I fell asleep. Maybe all parents do this.

On long car rides when she napped, when her body went limp and her head slumped forward, I reached my hand behind me from the driver’s seat and bounced her leg, worrying that her trachea would be compressed and she wouldn’t be able to breath. Sometimes, on the highway going 75 miles an hour, I shouted at her until she woke up or took a long inhale and repositioned her head.

I still left nightlights on around the house when my husband worked his overnight shifts at the hospital. Most months he worked up to seven such shifts. I had my cell phone next to my bed. I thought about the steps needed to make an emergency call in the middle of the night, and I reminded myself before I went to bed: swipe right, emergency call button, bottom left. Most nights, I watched TV as late as I could stand because the sound made everything feel normal.

The summer of her third year, we took a trip to San Diego, to Mission Bay, where my family had escaped August in Arizona since I was little. This year, my sister and I sat on our beach towels away from the shoreline while my husband swam with our daughter in the hotel pool. We sat there for an entire afternoon watching emergency workers, police, fire, helicopters, and boats search for a boy who had fallen into the water from a kayak, unable to swim, wearing no life jacket.

The search and rescue gave way to just a search. We watched the lead police officer, the one with the socks pulled up above his calves, eat two full sandwiches on white bread from the passenger side of his SUV. We watched people being interviewed, people falling to pieces, people still swimming in the water—ignorant or indifferent.

We watched as daylight turned to twilight, then into a scene that resembled a painting of night fishermen—darkness surrounding one little boat and one light source seen from the shore. We hit refresh on our search for “foreign exchange student drowned mission bay.”

The passenger ferry rides between two sister hotels across the bay resumed with the boy’s body not yet recovered, and my family wanted to go. Shaking, I declared that I would not set foot on the boat and neither would anyone else. That boy’s body was still under there, blue, like the surrounding water. Couldn’t they see his shape? Couldn’t they feel his stillness—the stillness of his chest? Couldn’t they feel the emptiness at their bellies?

He was somebody’s baby. At least I could be a witness. A witness for his mother who had no idea I was there. The next year, we returned to the bay, and I put flowers in the water for him—for her.

• • •

Every year since the birth, people ask me when I’m going to have another one. I can tell you that even after the pills for post-partum OCD, there is no way to forget. But forgetting is not the point.

Years after the birth, a friend suggested EMDR to deal with my continuing post-partum PTSD. The acronym EMDR stands for Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing therapy. It’s a form of psychotherapy that uses the patient’s rapid eye movements to help process powerful memories from traumatic events.

I found a therapist who I’ll call Judy (it’s not her real name). Before and after each session, she asked me, “What’s your disturbance level?”

I held the little black tappers, one in each hand. When I was ready, they alternated, vibrating first in my left hand, then in my right hand. Judy asked me to call to mind the most disturbing image or feeling I associate with my daughter’s birth.

I closed my eyes and felt the buzz, buzz, buzz, buzz, back and forth between my hands. I saw the round, flaccid body of my daughter when she flopped out of mine. She was slippery and a shade of purple-blue. That was the moment I knew something was wrong, when something told me I’d birthed a dead baby.

Judy stopped the tappers and said, “Okay, take a deep breath.”

I told her what I’d seen and felt.

“Okay, go with that.”

I closed my eyes again, and she started the tappers. In my mind, the image shifted from my daughter, and I saw my husband, the ER doctor, jump in with the nurse to work on her before the NICU staff arrived. He rubbed her body, using tactile stimulation to get her to breathe. She still wasn’t breathing, and he was getting ready to intubate her.

I floated above it all, watching. I could see myself in the hospital bed, alone, with the curtain drawn between my bed and the table where he was resuscitating her. Even though they were behind the curtain, I could see it happening.

Judy stopped the tappers and asked me to take a deep breath. She told me I was doing a good job.

I closed my eyes, and the tappers started again. My attention shifted to the doorway, where I saw my baby as they rolled her to the NICU. The doorway was filled with a white light, an incredible light I could feel in my heart. It felt like it contained everything in the entire world.

My eyes were still closed, and the tappers continued. Tears fell silently from my eyes.

“Okay, deep breath. Go with that.”

I held my baby’s foot. She was hovering above the table, and she wanted to be a part of the white light.

Judy asked if I was okay. I said I wanted to continue.

“Deep breath,” she said.

I closed my eyes again. I felt the tappers and saw my deceased grandmother sitting in a chair by the window. I knew she was with us.

She was the grandma who helped raise us, who lived just three blocks away. She lost two children of her own: the first, a five-year-old, run over by a truck, the second electrocuted at the age of 33 working on power lines.

She told me, I just didn’t want you to hurt.

Deep breath. Go with that.

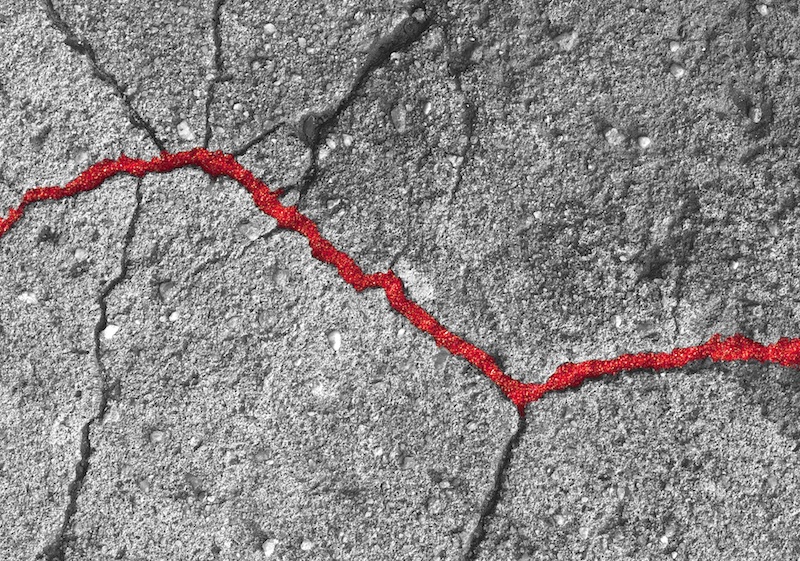

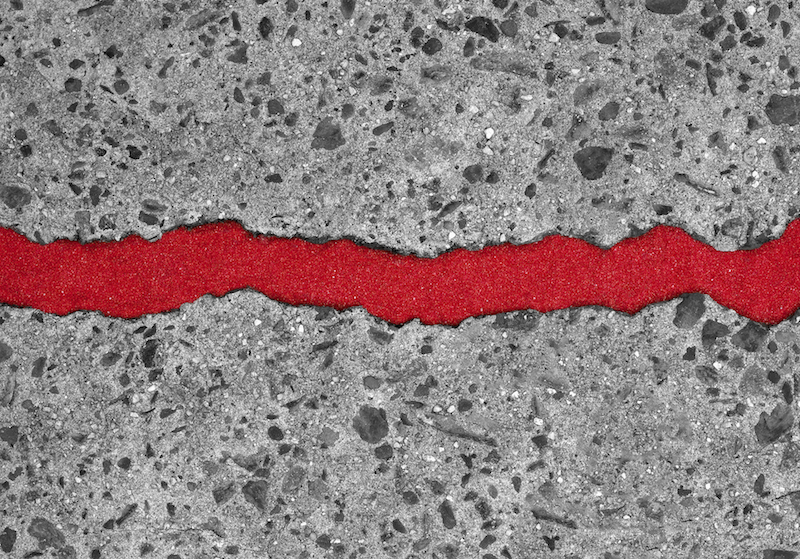

Art Information

- Images from the Red Sand Project © Molly Gochman; used by permission:

- "Red Sand Project (14)"

- "Red Sand Project (9)"

- "Fine Art Cracks RSP (16)"

Sara Hubbs is a multimedia artist and writer originally from Phoenix, Arizona. She completed an MFA in Visual Art at the George Washington University in Washington, D.C., and has shown nationally and internationally in Mexico City, Abu Dhabi, New York City, and elsewhere.

Sara Hubbs is a multimedia artist and writer originally from Phoenix, Arizona. She completed an MFA in Visual Art at the George Washington University in Washington, D.C., and has shown nationally and internationally in Mexico City, Abu Dhabi, New York City, and elsewhere.

Sara’s prose work will be published in a forthcoming anthology from Talking Writing. She was recently chosen for the 2017 Tucson Festival of Books Masters Workshop and has an upcoming two-person show with architect Will Bruder at Modified Arts in Phoenix. Sara lives in Tucson with her husband and daughter.

For more information, visit Sara Hubbs's website.