Essay by Martha Nichols

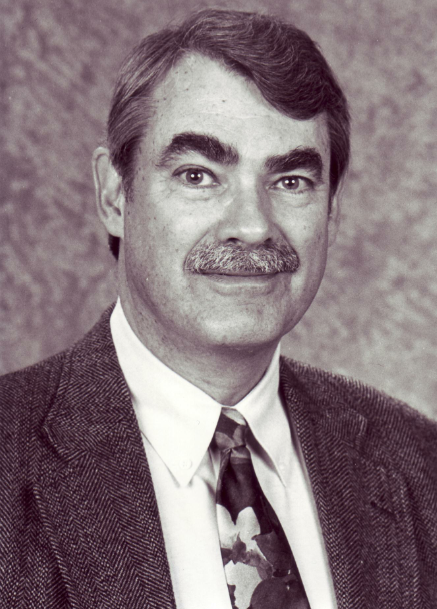

For My Father: James Nichols (1933–2014)

On Friday night, I told my father we’d bring over what he needs: a bookcase, an armchair. For the third time, he asked me if he was moving tomorrow.

“No, on Sunday, Dad. You’re moving on Sunday.”

“Can we work on the poetry?” he said then. “That’s the thing.”

When I arrived that evening in June 2010, I was exhausted from my cross-country flight, the three-hour time difference, Friday rush hour traffic, the hellish creep across the Bay Bridge. My mother was a mess. But even so, I typed my father’s latest poem on my laptop, working from the scraps my brother had written out and Dad’s slow recitation.

It was the weekend before Father’s Day. I fought my own melancholy, the sense that I was doing grave injury to someone helpless to change his fate.

In his prime, my father was never sentimental. Now, he had advanced Parkinson’s disease, and he knew it was time to leave home. He knew. But that didn’t change his nervousness, the potential for him to go mulish at the last minute.

The next morning, he said he’d had a terrible night’s sleep. He was weak, his drugs hadn’t kicked in. He didn’t think he could do it.

“Maybe I’ve had a stroke,” he said.

“No, Dad. Just wait for your medicine to work. There’s no rush.”

Although of course there was a rush. It was Saturday, less than 24 hours to go.

“I’m in a deep hole,” he said.

I wanted to take him to the new place again for a quick visit, so he’d worry less. So I’d worry less. He would tell me what he wanted in his room at the small board-and-care: which books and family pictures, which diplomas. I wanted this thing done.

He started to talk about the CIA in Vietnam and how somebody listed him as a reference in obscure academic papers—as a CIA cover?

“Did you read all the Vietnam stuff last night?” I asked wearily.

“No, no. I got rid of that months ago.”

Yet the night before, the delusions had plagued him again, another gyration of Parkinsonian paranoia. Sometimes he even knew they were delusions.

A CD blared in the background, Muzak versions of famous movie songs. The theme from Dr. Zhivago (“Somewhere My Love”) played, an especially ironic counterpoint to my father’s calm assessment of machinations in post-1954 Vietnam and the people he knew later in the Nixon administration.

“I kept the article with that footnote,” he said. “They misspelled my name.”

Could it be true? We were talking about the CIA; my father was a retired political scientist who had specialized in Mao’s China. Dad’s voice sounded low and slurred, but he was putting complicated sentences together.

“Can you show me the reference?” I asked.

Oh, no, he said. He’d had his home caregiver throw it away. Somebody was walking around with his name, a CIA ghost.

Round and round we went. Sense and nonsense from a man whom I’d loved forever, whom I’d always admired for his sharp wit—who pushed me to paroxysms of impatience, as if I were still fifteen and sick of his Socratic method, the way he would scoff at all my heated arguments for why the world needs to be a better place.

I remember collapsing on the floor in a fury, pounding my fists against the puke-green shag, my dashingly handsome father looking down, his eyebrows raised.

What’s wrong? he’d ask. I was supposed to be his best student.

In this, he would never change. The Parkinson’s had brought certain character traits to the fore. Rational me coolly assessed the good with the bad, but what struck me most was how much sweetness had floated to his surface.

He was Yuri Zhivago, stuck in a snow storm. That Saturday it was hot in the Bay Area, Mediterranean weather, and so far from a wintertime dacha with Hollywood icicles that the connection only made sense to me: the saturated blue sky, the Muzak, my father’s achingly long pauses between words.

Again, he wanted to go over his latest poem. He kept talking about how strange he felt, how dark. He told me he couldn’t stand up—but the poem?

I gave him the pages I’d printed out, and they rattled in his hand.

“Do you want me to read it, Dad?”

He huddled in his chair, still staring at the pages. It was his last day at home. I was poised on the couch, ready to run.

“Yes,” he said. “Yes, you could do that.”

So I read “A Ride to the Church Yard,” and his body relaxed. I knew then he would make the visit that morning. Although my brother and mother were as jittery as cats in a sack, I knew we’d get him moved on Sunday. Their anxiety fed my own, but I knew how to retreat to the dacha, too.

I know what poetry can do.

It was almost as if I could foresee the moment later that afternoon, when my brother and I drove to Target to find a few more things for Dad’s room, when we stopped talking about logistics. The silence sank in between us, suburban bungalows and strip malls passing on either side, long-winded rationalizations no longer conveying any of the emotional essence.

“Life,” my brother said. “You know?”

Or as if I could envision the next day—because Sunday did come, hot and bright—when Dad and I walked slowly up the ramp of his new home.

He clutched my hand, and I felt his fingers bucking. They were always in motion, but he held on as hard as he could. He took his tiny, tiny steps forward, and I matched his pace—there’s no rush, Dad—as one of the caregivers in blue opened the door.

A Ride to the Church Yard

By James Nichols

Josh, the funeral home driver

Shivered at the damp and cold.

Riding beside him was the tow-headed ten-year-old

And his two giggly baby sisters,

Hair all shiny like spun gold.

As they turned in the gate beneath the tower,

Josh thought, Sure enough, that mouthy boy

Will say something all too bold.

“Sir, does that clunky clock keep good time?”

Enough for all you’ll ever need.

“Sir, why are those rotting flowers piled everywhere?”

To keep the squirrels from running through your hair.

“Sir, why does that rusty old box stinketh so?”

Because your nose is too damned big, you brat.

“Sir, are you speaking? What was that?”

You insolent pup, let me fling this box lid up.

Now see what you’ve got.

The boy stood stock still, like one dreaming;

No sound was heard except the young girls screaming.

Lines of pity creased the old man’s face.

Gently, Josh said, “Come, child, every family

For grief must have its place.

And now we all must attend to

Our own souls’ redeeming.”

The boy took his hand and went, content.

Afterword: In Memorium

My father passed away the morning of January 22, 2014. By that point, he had moved several times, until he arrived at his last board-and-care home, a kindly place where he lived his final two-and-a-half years. He died peacefully, in hospice care, several days after a stroke took him down. My brother Mark and I were with him, as were the caregivers Dad had grown fond of.

He was a remarkable man, a well-loved professor, student adviser, and former dean at what is now called Cal State East Bay in Hayward, California. (We knew it as Cal State Hayward when he worked there.) He was a political scientist who specialized in China studies, but also taught courses in California politics and “Vietnam and Watergate.” From an early age, I remember his blow-by-blow accounts of Republican and Democratic conventions, as if he were reporting sports events.

He was a remarkable man, a well-loved professor, student adviser, and former dean at what is now called Cal State East Bay in Hayward, California. (We knew it as Cal State Hayward when he worked there.) He was a political scientist who specialized in China studies, but also taught courses in California politics and “Vietnam and Watergate.” From an early age, I remember his blow-by-blow accounts of Republican and Democratic conventions, as if he were reporting sports events.

In 1968, late one June night, we sat together in shocked silence, watching RFK’s assassination unfold on TV. I clung to his hand with all my might.

My father’s strong moral compass and deep love of literature, especially poetry, have made me who I am. Because of him, I’m a skeptic, a critic, a journalist, an editor. Most of all, I’m a writer. It never has been easy to make a living as an author, let alone to start a literary magazine like Talking Writing, yet my belief that creative work can make a real difference goes straight back to my childhood: to my mother the artist and my father the academic. It’s as ingrained in me as religious faith.

Dad was first diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in the year 2000 and endured a series of medical ups and downs—including other small strokes—throughout the succeeding decade. But one of the most astonishing transformations he went through was a creative one. After he stopped teaching at Cal State in 2002, he spent several years writing poetry. He'd wanted to be a writer for decades, ever since he was an English/Journalism major at the University of Denver in the early 1950s. By the time he graduated at the precocious age of twenty, he'd switched to the social sciences, but—goddammit!—he finally achieved his literary goal in his seventies.

In the early stages of Parkinson’s, the dopamine drugs that patients take can spark intense bouts of creativity as well as hallucinations. These side effects have been well documented by neurologists like Oliver Sacks. But I prefer to think of my father’s late-life poetry writing as a gift conferred by capricious fate.

I doubt he would have chosen two years of intensive creativity over a far longer, healthier life in which he could converse about Obamacare and California going to hell in a hand basket (just for example) with his family and friends. Still, I’m not sure, because I know how much his poems mattered to him.

My mother would copy the cramped handwriting of his early drafts into neat copies on yellow legal pads. He was the love of her life—and she his—and Mom urged him to keep writing, until she herself succumbed to Alzheimer's. She died in January 2013, and I think it's no accident his death came only two days shy of that sad anniversary.

Four years ago, when I first wrote "I Know What Poetry Can Do," I was helping my dad edit his work. I'd already put together one slim chapbook of his poems called October Notes, which he’d distributed to many friends and colleagues. “A Ride to the Churchyard” became part of a second chapbook in 2010. By then, when my brother could no longer care for him at home, Dad was running out of creative steam. Yet, he continued to talk with me about his poems years after he could put pen to paper or dictate anything. Most recently, I read them aloud to him—as I did while sitting vigil beside his bed during his last days.

In that shadowed, humidified room, I also read sections of poet Christian Wiman’s essays about creativity and mortality in My Bright Abyss. I returned to Michael Ryan, downloading his New and Selected Poems on my Kindle in order to dip into some of the contemporary poetry my father loved best.

At the private viewing after he died, my brother and I read some of Dad’s poems as well as Ryan’s "Extended Care," a particular favorite of his. “I’m not ready to write my last poems,” Ryan begins. And the ending lines of “Extended Care” had us both sobbing, even as a I recited them over our father’s silent body:

Everyone will appear to me as a scarred soul

struggling with the same sort of torments and disappointments,

as death rises like a dinosaur out of the duck pond

and lumbers dripping toward me on the sun porch

where I glow with the modest good I did with my life,

grateful this gorgeous world will be here for others when I am gone.

Amen, Dad. You're gone, but you're still with us, too—and yes, the world is gorgeous, always.

Publishing Information

- New and Selected Poems by Michael Ryan (Houghton Mifflin, 2004).

Art Information

- Photo of James L. Nichols (1995) @ Nichols Estate; used by permission.

- Untitled beach photo © rachjose; stock image license.

Martha Nichols is Editor in Chief of Talking Writing.

Martha Nichols is Editor in Chief of Talking Writing.

An earlier version of this piece appeared in Salon and Athena’s Head as “For Dad: I Know What Poetry Can Do” (June 16, 2010).