Theme Essay by Jeremiah Horrigan

A Journalist’s Search for His Karass

There was a time when I could hardly imagine a world without faith. It was something I took for granted, like blizzards in my hometown of Buffalo, New York.

Buffalo was my hometown only in the strictest sense of the word. I grew up in a place that didn't exist on any municipal map. I grew up in a parish. St. Martin's Parish. The Catholic faith, as it was practiced, understood, misunderstood, and enforced in the late 1950s and early '60s, was my daily bread.

I sometimes describe St. Martin's as a Catholic ghetto—all-white, working-class, first- and second-generation Irish, Italians, Poles, and a few Germans, the sons and daughters of World War II vets who built the suburbs if only to provide a place to raise all the babies that boomed from a dearth of contraception and an abundance of Papal edicts.

I loved growing up in a neighborhood crawling with kids living in newly built two-story wood-frames, cottages, and Cape Cods on streets that had been laid out with geometric precision, every curbside plot of grass planted with an American elm.

It was under those elms I would run at dawn, half afraid of the winter's dark, my pure-white altar boy's surplice snapping in the wind on a wire coat hanger slung over my shoulder. In five minutes, I'd have slipped into the church sacristy, donned a black cassock, stuck my head and arms inside the surplice, lined up with three other boys my age, blessed myself, and, at a nod from the priest, rung the bell that would begin my day with words as ripe with mystery as the Mass itself:

"Dominius Vobiscum," the priest would say.

"Et cum spiritu tuo," I would answer.

Growing up Catholic, in a community of faith saturated in mystery and ritual and the promise of eternal life, was as close to heaven as I ever expect to get.

God Almighty, it was great while it lasted.

• • •

Faith is a word I use sparingly, some fifty years after my altar boy days. It's not a word you often hear on the lips of smart, sophisticated people. But I've found that the more I write about things that matter to me, the more I yearn to regain that faith, in what I'd call its original form.

The faith I grew up in was a place provided me by the Church. Within its confines, I could look out on the world around me and feel safe. These days, faith still feels like a safe harbor. But the safety I seek is not that of walling myself within the confines of doctrine. Rather than gazing outward at an “unsafe” world, I want to participate fully in the world. Attaining such faith is a lifelong process, yet it feels more necessary than it ever did when I was a kid.

Back when I started my career in journalism, in the wake of the Watergate revelations, I thought I'd found that harbor. I came to journalism thinking I'd bring understanding to chronic problems. Expose wrongdoing. See justice done. After all, hadn't journalists just brought down a crooked president?

Turned out, as more than one editor had to remind me, journalism was a job. It had everything to do with other people's stories and next to nothing to do with my own.

"Who cares what you think?" was one guy's way of telling me to cut the romanticism.

The answer was "I care," although I never answered that question aloud. But I've always believed that I would one day prove to myself that what I cared about could also be of interest, even of value, to others. And I found the means to do so in the writings of a forgotten teacher whose messenger is revered among believers and nonbelievers alike.

• • •

Lionel Boyd Johnson, otherwise known as Bokonon, divvied up humanity in a way I recognized. He said humans were organized into teams that do God's will without ever discovering what they are doing. He called each such team a karass.

"If you find your life tangled up with somebody else's life for no very logical reasons," he wrote, "that person may be a member of your karass."

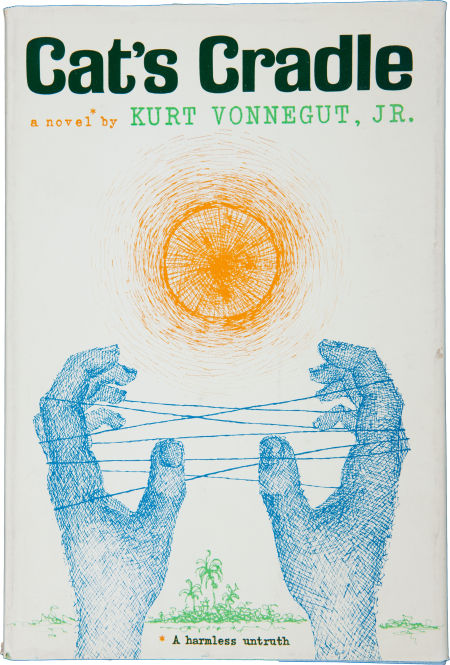

Readers who know Cat’s Cradle, a book that took root in me in the mid-1970s, will recognize Kurt Vonnegut's hilarious and still-timely creation. A karass ignores every national, institutional, occupational, familial, and class boundary. It is, Bokonon liked to say, as freeform as an amoeba.

The Church was exactly the opposite of a karass. It was what Bokonon called a granfalloon. Other granfalloons were "the Communist Party, the Daughters of the American Revolution, the General Electric Company, the International Order of Odd Fellows—and any nation, anytime, anywhere."

The Church was exactly the opposite of a karass. It was what Bokonon called a granfalloon. Other granfalloons were "the Communist Party, the Daughters of the American Revolution, the General Electric Company, the International Order of Odd Fellows—and any nation, anytime, anywhere."

The General Electric Company, as it turned out, had once employed Bokonon's one and only messenger: Vonnegut.

Cat's Cradle didn't just presciently mock the New Age, which was busy being born when I read the book. Bokononism may have been intended as satire, but Vonnegut's idea of a karass appealed to me; it posed a tart and attractive alternative to all the granfalloonery of my life.

Knowing all too well what I'd rejected, I now had the outline of what I needed: I had to find my karass. I've been on that road, looking, ever since. I've wandered through thickets of New Age nostrums, beaten my way around patchouli-flavored drum circles, dervish-danced myself dizzy in the name of altered realities that never lasted longer than a weekend.

That road took me farther and farther away from the Church and all the world's other calcified religions. But it didn't deliver me to religion's seeming opposite: the frosty, hypercritical world of atheism.

Tomorrow, I'll go to work at the newspaper, my current granfalloon. I need neither Bokonon nor Vonnegut to tell me how easy a granfalloon is to find or how difficult it is to recognize a karass. Turns out I’ve been in one since before I read Cat’s Cradle, a two-person karass encompassing me and my wife Patty, whose life has been tangled up with mine for nearly 45 years. There’s been nothing logical about it. But what’s logic got to do with love?

And, ultimately, a karass—whatever it may be, wherever you may find it—will only take you so far. I’ve found there’s work I have to do, and no one can do it for me.

• • •

What I've found for myself, after all those years of stumbling and studying, watching and listening, doing and not doing, is a faith that's as down-to-earth as any God-leering skeptic could wish, while at the same time if not exactly heavenly, then very much not of this world.

Thirty years on the road has given me what I need to construct a safe harbor of my own. Here's what it looks like, this place: It's a room with a large square table at its center. The table is piled with books, tchotchkes, unopened mail, notebooks of no particular significance, a pair of laptops. Along the periphery of this table, three couches and a chair. Behind the chair, a wall of books, most of them about spirituality, almost all unread by me.

This is the place where the world I've come home from drops away. Just now, the lights are dim, the air fragrant with dinner's afterglow. Music plays distantly on headphones I'm not using. It's the living room, in the fullest sense of that phrase. It's where I come alive, where I write.

This place could just as easily be a kitchen or a campfire or the driver's seat of my car. For me, faith is a place, not a belief, one born of innocence and wonder, a shelter that allows a writer to do what writers have always done: observe closely and carefully the ways of the human heart. My harbor is wherever I am, whenever I remember that I am.

And so I sit here, in this cluttered room, in a place where once again I'm running down a familiar elm-lined street, chased by a winter wind, running toward warmth, toward a godliness that once gave comfort and that now, I hope, embodies what I'm running toward at this moment, feeling neither cold nor fear, distilling the essence of a long-ago experience from the safety of the harbor I've finally found.

Publishing Information

- Cat's Cradle by Kurt Vonnegut (Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1963).

Art Information

- "Searching" © John Evans; Stock Image License

Jeremiah Horrigan is a contributing writer at Talking Writing.

Jeremiah Horrigan is a contributing writer at Talking Writing.

He is finishing work on his memoir Fortunate Son: a Father, a Son and the War on the Home Front.