Essay by Martha Nichols

Kitchen Table Politics—Again

It’s 6 p.m. on Saturday, the tail end of the AWP conference. After three days of literary hobnobbing, I’m floating on fumes of caffeine. Still, a few of us linger with the panelists of “Addressing the Silence: Editing as a Political Act.”

We’re talking about the boulder female authors keep pushing up that metaphorical mountain.

During the panel, four redoubtable women—Joy Castro, Sarah Fawn Montgomery, Nuria Sheehan, and Kate Ver Ploeg—focused on their experience of editing an all-female issue of the journal Brevity at the behest of Editor Dinty Moore. They emphasized what a difference it makes when women editors work together in a “mindful” way.

I can’t fault the bravery of a panel that calls editing a political act. But I’m restless. They’ve detailed their “collaborative” and “relational” process in putting together a single issue of creative nonfiction. But I want more heat, more passionate ruckus, especially after a conference in which gender politics seemed like either a sound byte or an affront to the keepers of the literary flame.

When they ask for questions from the audience, I jump in, saying how much I hate all-women’s issues. The panelists nod ruefully. Someone else comments that special women’s issues are like “Black History Month” or any other cultural ghetto.

“It’s about consciousness raising,” I say, acknowledging my own exhaustion at the prospect. “I can’t believe we’re back here again.”

“I feel like we’ve gone backwards,” says Lorraine Berry, my TW colleague.

“Well….” I gaze at the ranks of empty chairs behind us. I think about how this small auditorium was intended for a much larger crowd than the scatter of people who showed up. Many sat in the very back rows, as if afraid to be seen.

Yet, a few men did attend, including the young male editor from a student magazine who’s still there, listening, who wants to know how to attract more women writers when most of the submissions he receives are from men.

“No, two steps forward, one step back,” I say to Lorraine. “Not backwards.”

Major cultural shifts are messy and not always perfectly resolved in the way we older dreamers want them to be. But I’ve been around long enough to know that the real tipping point comes when the power players push back.

And they are pushing back. I have to stifle a laugh at recent querulous complaints about women ruling the publishing world (cue eye rolls) or the need to dumb down literature for women readers with lowbrow tastes.

Oh, yes. We’ve been here before. Except, courtesy of VIDA: Women in the Literary Arts, we’ve now got hard numbers to prove how much of a disparity remains between male and female writers—even in the twenty-first century.

The VIDA Bomb

Every year, the Association of Writers & Writing Programs conference offers a snapshot of the literary universe. At the 2013 conference in Boston, there was buzz about essays vs. memoirs. There was also plenty about the gender gap.

On Thursday, side-by-side sessions addressed “Women Writers in the Contemporary Literary Landscape” and “Second Sex, Second Shelf? Women, Writing, and the Literary Marketplace.” Saturday afternoon included three sessions in a row sponsored by VIDA, the organization that instigated the infamous “VIDA Count.”

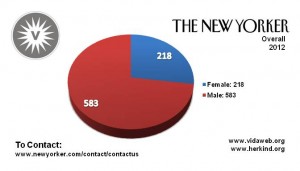

Since 2009, VIDA has been tracking how many women authors and book reviewers appear in prestigious literary journals such as the New Yorker, Times Literary Supplement, and Paris Review as compared with their male counterparts.

The numbers are dismal. For example, in 2012, Harper’s reviewed books by 54 male and 11 female authors; that same year, the venerable journal included book reviews by 3 women and 28 men. At the New Republic in 2012, there were 52 female bylines compared with 230 male bylines. And so on.

This is not news to any feminist editor or writer. Yet, ever since VIDA released its first count in 2010, the numbers have set off a small bomb in the halls of academe and magazine publishing. One full Saturday session at AWP—“Numbers Trouble: Editors and Writers Speak to VIDA’s Count”—pitted feminist writers like Katha Pollitt and E.J. Graff against Stephen Corey of the Georgia Review.

Corey, rather than addressing the questions raised by the Count, lobbed a few grenades of his own at the audience: “If there are fewer women published but their page counts are higher than men’s, is that okay? When you read, do you care that something is by a woman? Should an editor care?”

Even Graff noted that individual women writers have to step up, too, instead of slinking off whenever they receive a rejection.

Such arguments echo the larger quarrel about why women can’t get ahead. Take Anne-Marie Slaughter’s recent piece in the New York Times Book Review about Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead by Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg.

Slaughter, a former State Department director who set off her own bomb with the 2012 Atlantic article “Why Women Still Can’t Have It All,” gives the hard-driving and optimistic Sandberg her due, noting that there’s a “real debate here.” But the conclusion of this excellent review draws the battle lines:

So is the dearth of women in top jobs due to a lack of ambition or a lack of support? Both, as Sandberg herself grants…[y]et she chooses to concentrate only on the ‘internal obstacles,’ the ways in which women hold themselves back. This is unfortunate…. When it comes to ensuring that caregivers still have paths to the corner office, how can business lean in?

I’d ask the same question of literary institutions. More than that, I have an answer: Editors need to lean in, way past their mostly white, middle-class comfort zones.

Feminist Editing—or Just Good Editing?

Given what VIDA has turned up, I don’t see how anyone in charge of a literary magazine can ignore the political and cultural impact of editors. That’s why I run my own magazine now. As in decades past, when feminists or other literary outcasts assembled their journals on kitchen tables, I view the editing I do as a vehicle for social change.

Yet, simply being female isn’t the ticket to elevated consciousness or a new way of editing. The fact that TW’s two top editors are women, for instance, isn’t enough to close the gender gap at Talking Writing, even if we do publish more women than men. What matters is our political awareness—and, most important, the emphasis Executive Editor Elizabeth Langosy and I place on the need for more than one voice in the editing process.

Collaboration between editors is certainly key, including arguing about what should or shouldn’t go in the magazine. When a group of editors takes the time to figure out why they like something—or not—unconscious biases often surface. In TW’s case, when Elizabeth and I disagree, it’s a good bet that the ensuing discussion will lead us to rethink or refine our publishing objectives.

Collaboration with writers is also a must. My focus when editing a personal essay is clarity of thought and feeling. If your argument and logic aren’t clear to me, they won’t be clear to readers, either. If your words distance me from what you’re feeling, I’ll push you to be as vulnerable as you can be on the page.

Sounds good, especially with writers who like such editorial intervention. But what does that nonpartisan approach have to do with politics or social change?

Everything. Editors at their best are mentors, encouraging critical thinking—and in a world in which so many business and political leaders use words to obscure what they’re doing, truth telling by authors is essential. It’s why I believe the developmental editing I do with inexperienced writers has the most impact. It’s the reason I’m a journalism instructor, too.

The “Addressing the Silence” panelists initially framed what they did as a “feminist editing process.” But I’ve worked with many good editors, male and female, and seen the same kind of collaboration and mutual respect in a variety of venues. What this panel dubbed feminist is what I call good editing, period.

Here’s where it gets dispiriting, though: To my mind, good editing is far more endangered now by cuts in arts funding and layoffs at big magazines than by conscious sexism. If you want a collaborative editing process, you need more than one beleaguered editor. You need more than one or two people running a literary magazine for no pay.

Otherwise, those lonely editors do what’s easiest—reach out to the writers they know, the guaranteed producers, the quick turnarounds. That’s particularly true for indie journals and those of us who don’t have overhead covered by a university.

You Are the City

It’s tempting to think that AWP organizers had nefarious reasons for relegating the “Addressing the Silence” panel into the last time slot of the conference, when many attendees were already at happy hour in nearby bars or the airport.

Regardless, the hushed room, the small audience, and the muted voices of the panelists—who themselves seemed dampened by the atmosphere—illustrated the literary silences that exist better than anything said.

Oh, how I want a big fat wave to wash right over the literary gunwales, to sink the boat that brought other AWP sessions like “Memoir Beyond the Self.” That panel’s mix of men and women seemed to back away from “memoir” and the “solipsistic” as if it were some kind of unmentionable female disease.

I want to break the silence about the power editors can wield, even if we women editors don’t feel particularly powerful. Because the power we have is real, and not just as a means to keep the literary riffraff out.

Two steps forward, one step back—but not backwards.

Despite VIDA’s latest count, I grab for whatever signs of hope I find. And at “A Centenary Celebration of Muriel Rukeyser,” the best AWP session I went to of many fine events, I felt sparked by what it means to love literature with all the intensity you can muster.

Rukeyser, a supremely humane and political poet, valued her role as a mentor to young writers like Sharon Olds. So, the now white-haired Olds regaled the AWP audience with what Rukeyser was like as a workshop instructor: mischievous, blunt, inspiring. But Olds also said her mentor talked about “the experience of being left out of an entire generation of anthologies because of her politics.”

In that full auditorium, which included attendees of all ages (more women than men, but plenty of men, too, including Rukeyser’s son Bill), I can’t say I felt touched by the dead poet’s spirit, as panelist Olga Broumas did. But I was touched by Rukeyser’s legacy. It does live on, and it was joyously palpable in that room.

“Look at your own building. You are the city,” Olds read from Rukeyser’s “Despisals.” As that 1973 poem concludes:

Never to despise in myself what I have been taught

to despise. Not to despise the other.

Not to despise the it.

“She believed that boundaries are false,” added moderator and Paris Press editor Jan Freeman, who pointed out that this writer’s work was so expansive, stretching from the Spanish Civil War to silicosis among miners in West Virginia to Hanoi during the Vietnam War, that “we too can be expansive in what we write about.”

When I was a grad student in the 1980s, shortly after Rukeyser died, she seemed like a well-kept secret. But encountering her again in the very public forum of the AWP this year was more than a nostalgic pleasure. I’ve now realized how thoroughly she’s infiltrated my beliefs about editing and writing.

Paris Press reissued Rukeyser’s long out-of-print book The Life of Poetry in 1996, and I bought a copy at the conference. Soon after, I also came across a 1997 Nation review of it by Eileen Myles. Her review gloriously encapsulates the “wolfish” tension between art and politics. As Myles puts it:

Muriel Rukeyser unspools one of the most passionate arguments I’ve ever read for the notion that art creates meeting places, that poetry creates democracy…. The Life of Poetry is a book about fear, about what a culture has lost through its failure to use its intimate powers.

Sixty-plus years after Rukeyser first published that lovely, oddball book, we’re still “talking writing” at the kitchen table. But the talk matters more than ever.

Like the poet who once exhorted us to “breathe-in experience, breathe-out poetry,” I believe talk about art and war and sex and parenting and social equality—all forms of creative dreaming—never amount to empty words.

Publishing Information

AWP 2013 Conference Schedule.

AWP 2013 Conference Schedule.- “The Count 2012,” VIDA, released March 4, 2013.

- “Yes, You Can” by Anne-Marie Slaughter (review of Lean In), New York Times Book Review, March10, 2013.

- “Why Women Still Can’t Have It All” by Anne-Marie Slaughter, Atlantic, July/August 2012.

- “Brevity 40 / Ceiling or Sky? Female Nonfictions After the VIDA Count,” Fall 2012.

- “Despisals,” originally published in 1973 and reprinted in the anthology No More Masks!, edited by Florence Howe (HarperCollins, 1993).

- The Life of Poetry by Muriel Rukeyser, originally published in 1949 (Paris Press, 1996).

- “Fear of Poetry” by Eileen Myles (review of The Life of Poetry), Nation, April 14, 1997.

- “Breathe-in experience, breathe-out poetry” is from Muriel Rukeyser’s “Poem Out of Childhood,” originally published in 1935 in Theory of Flight.

Art Information

- "Talking to the Hand" © Gabriela Camerotti; Creative Commons license

- The New Yorker 2012 VIDA Count © VIDA; used by permission

- "Talk to the Hands—on the Level" © Ian Burt; Creative Commons license

- "Muriel Rukeyser" © William L. Rukeyser; used courtesy of William L. Rukeyser

Martha Nichols is editor in chief of Talking Writing.

Martha Nichols is editor in chief of Talking Writing.

For Martha, rediscovering Muriel Rukeyser’s The Life of Poetry—and reading Eileen Myles’s review—was an unexpectedly resonant outcome of this year’s AWP conference. “It’s rare that we have access to words directly from another era, to talk about literature and life,” noted Myles in 1997, calling The Life of Poetry “a book of talk” in the best possible sense.

Perhaps Rukeyser’s spirit has been with Talking Writing all along.

TW Associate Editor Lorraine Berry contributed to some of the reporting for this article.