TW Interview by Lorraine Berry

Last November, when we spoke by telephone, Robert Olen Butler was charming. And patient. On the tape of our hour-long interview, you can hear my dogs tussling and trying to knock the phone out of my hand. His dog, who he said was with him, no doubt slept blissfully at the foot of his master.

I'd originally called Butler to talk about literary gatekeeping—the theme for this issue of Talking Writing—and his response was unexpected. When I asked about his experience as a judge for contests like the National Book Award, he quickly corrected me. He explained exactly why he refuses to judge such awards, even though he was the 1993 winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for the short story collection A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain.

Butler began his writing career as an acting student at Northwestern in the sixties. As his love of writing emerged, he switched majors and wrote plays. He claims he was “a terrible playwright,” though. As he told me:

Butler began his writing career as an acting student at Northwestern in the sixties. As his love of writing emerged, he switched majors and wrote plays. He claims he was “a terrible playwright,” though. As he told me:

My most impassioned writing went into the stage directions. Now, that’s a bad sign. I was really a closeted fiction writer.

After leaving school, he served in Vietnam in the early seventies. Since then, he has published twelve novels and six volumes of short fiction. He currently teaches creative writing at Florida State University and lives in a small town nearby.

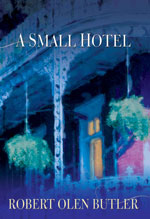

His most recent novel, A Small Hotel, was published last fall by Grove Press. In it, main characters Michael and Kelly Hays are on the brink of ending a twenty-year marriage. On the day their divorce is to become final, Michael spends the weekend at an antebellum mansion with his new—and much younger—flame, Laurie. Meanwhile, Kelly has fled their marital home in Pensacola, Florida, to return to the small hotel in New Orleans where she and Michael first began their romance.

Some critics have thought this novel contains autobiographical elements from Butler’s most recent divorce. Regardless, I found A Small Hotel lyrical, full of shimmering imagery. The characters of Kelly and Laurie are especially resonant: one woman grieves the loss of a marriage; the other tries to compete with a past that, it is clear, Michael, too, mourns.

Some critics have thought this novel contains autobiographical elements from Butler’s most recent divorce. Regardless, I found A Small Hotel lyrical, full of shimmering imagery. The characters of Kelly and Laurie are especially resonant: one woman grieves the loss of a marriage; the other tries to compete with a past that, it is clear, Michael, too, mourns.

During our interview, Butler and I also connected when we talked about teaching writing. We discussed material about the writing process that has appeared in previous interviews or can be found in his book From Where You Dream: The Process of Writing Fiction (Grove, 2006, edited by Janet Burroway). For that reason, some sections of this TW interview have been condensed.

TW: I understand that you are the mayor of your own town. Population: two.

ROB: Originally there were seven. One person died; a family of four moved out and took their home with them.

TW: Do you have a compound?

ROB: Do I? I live in a historic home. A wonderful antebellum home on the National Register of Historic Places. I have a separate writing cottage. It’s a terrific place.

TW: That sounds absolutely heavenly to most writers. Is that why you have turned down the opportunity to judge contests?

ROB: With the National Book Award, for example, each judge is responsible, theoretically, for 2,000 books. I mean, to choose the best work of literary fiction of the year, you need to read all the literary fiction from whatever source.

My deep conviction is that if you read literary fiction too fast to hear the narrative voice in your head, you’re not reading at all. A work of art is an organic object. Every tiny comma stroke should be crucial to the ultimate vision of the work. And real art, all works of art, are sensual objects. The literary novel is no different from a symphony or a ballet or a motion picture or a painting. It exists in the realm of the senses.

But with speed reading, which you have to do to judge a contest, you begin to work conceptually; the sense details that accumulate in a real work of art—and that by their basic patterning ultimately yield the unique knowledge of the human condition—are lost. So I can’t, in good conscience, judge a contest where the very essence of its selection process would make it impossible for me to adequately distinguish between works of art.

By the way, you can always identify when a writer is pathetically inflating his or her resume by saying they were nominated for a Pulitzer Prize. Unlike the short list, which suggests you‘re on a list for finalists, to be “nominated” for a Pulitzer means that your publisher sent in a book and 25 bucks. Basically, everybody gets nominated.

TW: Are you aware of when you started reading literature as literature as opposed to what you’re calling speed reading?

ROB: I never did speed reading. I guess it was because my early interest was in acting; in fact, I was trained as an actor. An actor respects the voice on the page, and I have to hear the voice in everything I read, and I knew instinctively that the voice would not yield if I was reading really fast.

But I came sort of late to writing fiction as a result. After writing a dozen bad full-length plays and getting a master’s for one of them, I went off to Vietnam and came back and started writing fiction. And that was my ultimate destiny.

TW: I find that an interesting choice of words. “Destiny” is a great word. It’s not something that we hear a lot. What does destiny mean to you?

ROB: The thing I find myself having to teach all my grad students is that art does not come from the mind; it does not come from the rational analytical faculties. Art does not come from ideas; art comes from the place where you dream, from your unconscious—what Graham Greene called the “compost of the imagination,” where all your life experiences dissolve out of conscious memory and into this deep well of self.

In some ways, the creation of a work of art is as much an act of exploration as of expression. You have an inchoate sense of what the human condition is all about, and the only way for you to know what it is, much less to communicate it, is to create an object. You are destined by what you know about the world and how you are shaped as a person; you are destined to express that in some medium. You don’t choose it; it chooses you.

TW: In their reading, my students often get impatient with authors; they want to figure out a book’s message instantly.

ROB: Unfortunately, what they are almost inevitably referring to is: How do I translate this experience into an abstraction? Into ideas? Into a philosophy? Into a theory? Into politics? Or whatever.

They’ve been taught that the artist is somewhat like an idiot savant. Artists really want to say abstract, analytical, theoretical, philosophical, political things, but they can’t really do it outright—that’s the idiot part. The savant part is that they create these novels and stories instead that do not have a meaning. You don’t know what they’re about. You can’t figure them out until you translate them into ideas or analysis. And that’s utter bullshit, not to put too fine a point on it.

You are not meant to understand it in an intellectual, abstract way. You are meant to thrum, like a string on a stringed instrument. When people get frustrated because they don’t know what the book is about, it’s because they’re trying to turn it into a college term paper. That is not only inappropriate, it is wildly dysfunctional.

TW: I’d much rather have a conversation with a student that begins, “When I read that paragraph, it made me cry.”

ROB: Sure.

TW: So, can we talk a little about your writing process—when you are exploring that “thrum” in your own writing?

ROB: I often cite Graham Greene. I don’t remember the exact quote, but he said all good novelists have bad memories. What you remember comes out as journalism; what you forget goes into the compost of the imagination. He’s clearly talking about life experience, and he’s clearly right about that.

But it’s also true about all the craft and technique that you learn, which is fine to learn consciously, but the only craft and technique you legitimately have access to is the craft and technique you’ve forgotten. What authors have influenced me? Well, I don’t remember. Not remembering them is how they are influencing me.

So, in terms of process and the thrum, I employ my good novelist’s bad memory, as every writer must, and I return to my work only after I have forgotten it in some sense. It’s not total amnesia, but at least when I read it, I am reading it fresh. I read and go thrum, thrum, thrum…twang! And I hit something that’s wrong. Just doesn’t work.

Now, in most creative writing classes, even if they allow that the first draft should be free form, when you go back and revise, then it’s fair game to analyze, to think about, to consult your technique—or the dozen other people who are sitting around you who don’t know any more than you do and are consciously trying to think of fixes—to put a scene here and move this there and whatever.

And of course that’s the problem to begin with. You’ve fallen out of the dream space. You’ve started thinking, and that’s probably why you got the twang to start with.

Instead, you should re-dream that passage. Rewriting is re-dreaming. That’s always the struggle for me in process. To get into that trance state to start with, to be in my unconscious, to be rendering the world primarily through moment-to-moment sense detail—and then, in the revision process, to return to those places that don’t work to re-dream until everything thrums.

TW: It’s a lovely way of thinking about reading and writing. I say that, of course, because it mirrors my own sense of what reading is supposed to be about.

ROB: Well done. You’re talking to the right people here. [Lots of laughing from both.]

The bafflement of the student is increased enormously by this. In some ways. But in other ways, you’re empowering their instincts and their own unconscious. I think it’s more baffling for a grad student than an early undergrad.

TW: How so?

ROB: Because they’ve been exposed to creative writing course after creative writing course. Most of the technique and craft courses are guilty of fostering these impressions as well—that the creative process involves at any point the analytical dissection of your own work. Not only is that not the creative process, it’s the antithesis of the creative process.

TW: Let’s talk about your latest novel, A Small Hotel. There was a phrase from the poet Yehuda Amichai that went through my head several times as I was reading your book: “To be an adult means to bake the bread of yearning.”

ROB: Yearning? Yearning is a major word in my pedagogy. I’ve long called fiction the art form of human yearning. That’s what makes all fiction go. What we understand as plot is, as I’ve often said, yearning challenged and thwarted.

TW: Why did you set this story in New Orleans?

ROB: New Orleans is a city intimately connected to my unconscious. I’ve been there maybe 200 times in my life. And in some ways, it is the city that is the antithesis of Pensacola, which is the life they (the characters) ended up making for themselves.

The life of openly expressed feeling is what New Orleans really represents, and that’s the problem here. Michael and Kelly do not speak the same emotional language. And New Orleans is also a city that is very conscious of its own vulnerability. One reason the partying is so hard and the life so intense is that everyone knows that at any time, on any given summer day, the city could vanish. In the midst of life, we are in death—that’s really what New Orleans is all about. And so is the book.

TW: I loved the various voices in the novel. And speaking of thrum, there were a lot of sentences that made my heart beat faster. I realize that part of it is a technique question, but also you’re capturing those dream sequences—

ROB: Sigh. It could be described as a technique thing, but it’s not a technique thing. It’s a voice thing, it’s a music thing, it’s a rhythm thing. Technique might examine the sentences and the metaphors, and deconstruct them. But the creation of it has to do with hearing the music of it and getting the rhythms right and embracing the organic wholeness of a work of art. Every metaphor not only illuminates the thing it’s trying to physically describe but also has the emotional valence and deep patterning that fits into everything else that’s going on in the book.

TW: I’m sure you’ve been asked this a million times: How are you able to put yourself into the voice of someone who is not you?

ROB: There’s a kind of surface answer, and there’s a deeper answer. The surface answer is that I’ve been married and unmarried four times, and I’ve been in a lot of relationships. I’ve listened to those women very carefully.

TW: Obviously not carefully enough.

ROB: Okay, that’s the funny answer. The real answer has to do with the artistic unconscious. The great Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa said that “to be an artist means never to avert your eyes.” So, if you write every day in this very vulnerable trance, into the welter of everything good and horrible that’s always there, you cannot look away. You have to face it. That’s tough.

But if you do that day after day and novel after novel—and you also ravenously live your life—what happens is that you break through into your own unconscious, where you are neither male nor female. You are not white, black, red, brown; you are not Christian, Muslim, Hindu, Sikh, or Jew; you’re not Vietnamese or American or Serbian or Albanian. You are human. At that point, where you have access to the collective unconscious, you will be able to express it through the vessels of characters that seem different from you.

TW: You must encounter many students who long to be writers. What do you tell them?

ROB: The danger of wanting to be a writer is that it generally means “I want to get published, I want to win an award, I want to have a book.” And if that’s what’s driving you as a writer, you’ll never create anything worthwhile—even if you’re capable of it.

By the way, after I wrote those 12 god-awful plays, I wrote 44 dreadful short stories, and 5 awful novels. I wrote a million words of dreck before I started writing really well. And none of that stuff got published. One of the problems I had was wanting to be a writer.

The work is the thing. The work’s the thing. The work is everything. I want to be a writer is different from I want to write. If you’re going to be an artist, the motive must be I want to write. Even if you never get published, you’d still write those books.

The smell of the place is always the same. Old wood and old rugs and fresh sheets and from the open balcony doors the sweet but tainted smell of the Quarter, jasmine and roux and shellfish brine, beer and piss and mildew, and something of the river too, and the swamp, and a hard rain that passed by, and ozone and coffee and sex, Michael's smells and her smells: can all of this be inside her in this room in this moment? Probably. She is weeping.

—from A Small Hotel, Robert Olen Butler

Art Information

- “New Orleans 249,” “New Orleans 264 B&W,” and “New Orleans 260″ © Adam Reeder; Creative Commons license