TW Interview by William Gray

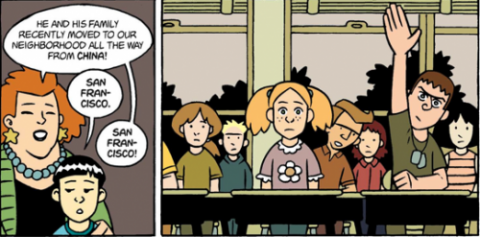

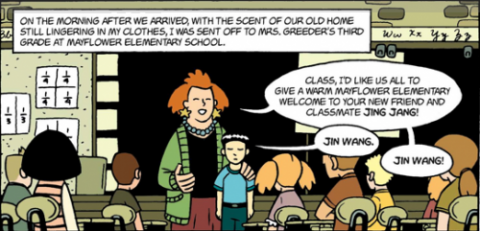

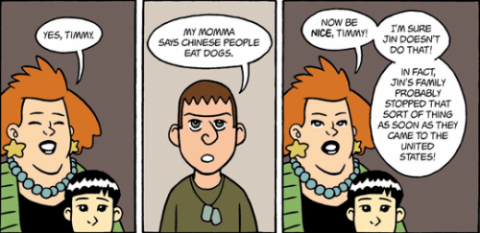

Gene Luen Yang's American Born Chinese (2006) was a National Book Award finalist. This unusual graphic novel about Chinese American identity also won the Printz Award from the Young Adult Library Services Association (YALSA).

Gene Yang, a high school teacher and cartoonist, has produced other books for First Second Books, a Macmillan imprint, including The Eternal Smile and Prime Baby. His first comic book was Gordon Yamamoto and the King of the Geeks.

Gene Yang, a high school teacher and cartoonist, has produced other books for First Second Books, a Macmillan imprint, including The Eternal Smile and Prime Baby. His first comic book was Gordon Yamamoto and the King of the Geeks.

TW editor William Gray, who interviewed him by phone in October 2010, says “Gene was very upbeat, happy, energetic.” They discussed American Born Chinese, ethnic identity, and what works in graphic novels—and what doesn't. As Gene puts it:

I’m glad that there are superhero comics for adults and for kids. But it’s gotten to the point where it’s a little ridiculous. The grim and gritty has jumped the shark. They’re shocking in a sort of ludicrous way."

TW: Are you defined by American Born Chinese?

GY: It’s the most commercially successful comic that I’ve done so far. It was in Borders from day one. But oh, it’s really hard to impress teenagers—so I don’t know. Every now and then, I’ll have a kid bring up a copy for me to sign, which is nice.

TW: You were a full-time teacher, and now you’re part-time. Did you use comics to teach?

GY: I did that in a math class. It worked really well—shockingly well. At the time, I was the school’s educational technologist, so I had to miss sessions with my math class every two or three weeks. To make up for that, I started videotaping lectures. Then I started drawing out those lectures as comics. Students would ask me to do that even when I was there.

I think comics are effective for a lot of reasons. There are just certain pieces of information that are best conveyed visually. And comics give the reader control over the rate of information flow. The reader can decide how quickly or slowly information is presented, as opposed to a film or animation, where it is at the pace of the director.

TW: What do you think of graphic novels as young adult literature?

GY: I think it’s a natural place for comics to be. There are three major comic book cultures around the world: America, France, Japan. In France and Japan, comics are read by the general population. They are not seen as weird or geeky, as they have been seen in America in the past.

Except for strips in newspapers, American comics were not mass medium before the 1950s—and they were read by mostly teenagers (and by G.I.s during World War II). But after the ’40s, we saw stories that didn’t necessarily involve fuzzy animals or superheroes. They were starting to tackle more adult themes and to get a depth of characterization.

Yet Fredric Wertham, a psychiatrist, had this thesis that was very misguided. He thought childhood delinquency was caused by excessive comic-book reading. That had a profound effect on the way comics were perceived in America. At that point, there was this division between strips in newspapers and comic books. [Wertham's 1954 book Seduction of the Innocent sparked a Congressional inquiry and the Comics Code Authority (CCA). The latter was created by a group of comic-book publishers to self-regulate the industry.]

I think the way comics developed in Japan and France was really the way they would have developed here without political interference. The popularity of comics in the past decade is a return to a more natural progression. We’re seeing comics targeted at practically every age range.

TW: Should we encourage children to read comics?

GY: Yeah, yeah, yeah. I read a lot of comics with my children.

TW: Something as culturally sensitive as American Born Chinese—was it therapeutic to draw and write?

TW: Something as culturally sensitive as American Born Chinese—was it therapeutic to draw and write?

GY: This was definitely a way to work out some issues with my ethnic heritage, of trying to figure out how my Chinese-ness and American-ness fit together. It’s fiction, but I definitely pulled a lot from my own life.

TW: And did it help?

GY: It did. But that book took forever. It took me about five years to complete.

I have a friend who used a breakup letter from his high school girlfriend in a book. He said that after he put that letter into a story, it no longer had that sting. He could remember those emotions in his head, but it didn’t touch his heart. And I kind of feel like that happened to me with ABC.

TW: I’ve read in other interviews that you’ve changed personal details in ABC: isolating two of your main characters in an almost all-white school environment, for example.

GY: It’s part of cartooning—trying to find the essence of something and simplifying it. That happens in both drawing and writing. I tried to model the two main characters in the Jin storyline on two groups of Asian-American boys.

There’s a group of us who were all American born. We spoke to each other in English. We were very comfortable with American pop culture. And then there was this other group of boys—most of them were born in another country—and they came much later. So they spoke with accents, and they were much more awkward in American culture, and often they would speak to each other in their native tongues.

We had these weird relationships, but we were friendly with each other. But my group always wanted to let people know we were separate groups. I felt like the clearest way to talk about it was to condense those two groups into two characters.

TW: Along with that, in the novel you also change the traditional Buddhist version of the Monkey King to the Christian God. Where does that fit in?

GY: I feel like my ethnic heritage and my religion [Roman Catholicism] are the two most important pieces of my identity and how I understand myself. As to why I put it into the Monkey King story, he’s such a popular character in Asia. I grew up listening to my mom tell me his stories, and when I started doing comics as an adult, I knew I was going to do that as a story. Every working cartoonist has done something with the Monkey King, and it’s usually close to a straight adaptation.

In the end, as this product took shape in my head, I decided I wanted to do an Asian-American telling of this. Christianity has had a profound effect on Asian American identity. I feel like it’s a particular style of Christianity that emphasizes where Western Christian morality and a Confucian-based moral system intersect. You visit any college with Christian groups or clubs, you’ll usually find a lot of Asians in those groups.

TW: There’s a sense of shame conveyed in American Born Chinese—a tug between Asian and American culture. Is there a place for shame in the graphic novel?

GY: If I’m honest with myself, I still do feel a little bit embarrassed when I hear somebody struggling with an Asian accent. But it’s less than when I was a child. I feel much more settled now as an American of Chinese descent, but I also think that’s an inherent part of being an American. Immigration is such an important part of the fabric of America. Once my parents moved here from Asia, they created a new branch within their cultural heritage. Chinese culture itself continued to develop, but they were not part of that development.

My wife is Korean, and when her Korean relatives come to visit her family, they remark on how it seems like they’re visiting a family from 1960s Korea. It doesn’t work the way a modern family in Korea works. Her parents took themselves out of that river and put themselves into a new river. I think we constantly feel that tension.

TW: Do you travel back to Asia?

TW: Do you travel back to Asia?

GY: I’ve been twice as an adult. Ten years ago, I led a tour of my high school students. That was my first time back in mainland China. We did the normal tourist route—Beijing, Shanghai, and all the big places you’re supposed to see. On the more recent trip, I visited an international school in Shanghai, where I did a book talk and workshops and such. Shanghai is such a crazy city, you can literally watch the landscape change.

TW: To you, what's a graphic novel?

GY: A thick comic book. Any comic book that has a spine is a graphic novel. It’s a silly term. It’s totally a marketing term, because comic books are not socially acceptable. I prefer the term comic book—it has more historical value and it is less pretentious. I started out reading Superman, but I haven’t read Superman comics in years. I find some of the stuff happening in the superhero world somewhat disturbing. They seem to have gotten grim and gritty. There are some exceptions—The New Frontier—and I like Watchmen, but there’s a lot of rape in superhero comics. There’s a storyline in Marvel comics where Spider-Man gives his wife cancer, because they imply his sperm is radioactive. In a sense, I’m glad that there are superhero comics for adults and for kids. But it’s gotten to the point where it’s a little ridiculous. The grim and gritty has jumped the shark. They’re shocking in a sort of ludicrous way.

TW: Which graphic novelists do you read?

GY: I admire Jeff Smith (Bone). Jay Stephens has moved into animation now, but I enjoy his work, too. In manga, I like Naoki Urasawa and his series called Pluto; Osamu Tezuka, too. As for superheroes, I’ve been reading Mark Waid’s stuff. His Irredeemable has some pretty disturbing imagery in it, but I feel like it’s done for a reason as opposed to for pure shock value. It assists the overall narrative.

TW: Where do you think graphic novels will be in ten years?

GY: It’ll be like television. There will be more diversity in terms of genre, readership, demographics, delivery systems. I don’t think print comics will go away by any means. They will have to distinguish themselves from digital comics by emphasizing the physical object-ness of the book. There are books like that, where the packaging and presentation itself is a work of art. They are designed to be objects held in the hands. I think the survival of print comics and print in general depends on publishers embracing that, and on authors and cartoonists embracing that.

TW: And what about your projects right now?

GY: I have one that will be released next year called Level Up, a story I wrote about a video game addict visited by angels. The angels tell him to give up video games and become a doctor, but he constantly wants to play video games. I've also done a short story for a recent Marvel anthology Strange Tales (volume two) about an obscure Marvel character called the Fabulous Frog-Man.

TW: Any advice for would-be comic book authors out there?

GY: Do it. Make a book. Start by self-publishing. I would recommend that to anybody. When you self-publish, you deal with printers, sellers, all of it. It’s a real education.

Art Information

- All panels that appear here from American Born Chinese provided courtesy of Gene Luen Yang and First Second Books; used by permission only.