Theme Essay by Elizabeth Titus

Why Can’t Our Favorite Writers Be Our Best Friends?

All writers have their idols, and I am no exception. Mine are Joan Didion and Maira Kalman.

I discovered Joan in 1974, when I used her first essay collection, Slouching Toward Bethlehem, in a ninth-grade class I taught at a private girls’ school in Philadelphia. I loved Joan; my students hated her.

I discovered Joan in 1974, when I used her first essay collection, Slouching Toward Bethlehem, in a ninth-grade class I taught at a private girls’ school in Philadelphia. I loved Joan; my students hated her.

“What’s her problem?” they asked. “Why does she take everything so seriously?”

I came upon Maira Kalman in the 1990s, when my late husband Gregory read her books about Max the dog to our small daughter, Lili. They’d roar with laughter as he read aloud from Ooh-la-la (Max in Love).

In his essay, “Voluminous,” Leon Wiesteler writes:

A wall of books is a wall of windows.

One wall of my living room is covered with bookshelves. They hold the books I’ve saved for Lili’s children; my collection of fiction and nonfiction; the architecture books acquired by Gregory over thirty years. These books are windows into our lives and tell who we were, how we lived, what we cherished most. They are our history, both shared and individual.

My literary idols are also a window into my life. Didion represents my time as an English teacher, when I met my husband. Kalman is linked to my becoming a mother in my forties and a widow in my fifties.

My literary idols are also a window into my life. Didion represents my time as an English teacher, when I met my husband. Kalman is linked to my becoming a mother in my forties and a widow in my fifties.

Until early 2011, I’d never met either of my idols. But that all changed in a matter of months, and the experience rocked me in ways I didn’t expect. In one case, I was severely disappointed, at least for a few moments.

More than anything, though, I realized that the personal connections we make with writers have less to do with them than with our own fantasies: of friendship, of finding a soul mate, of belonging to an exclusive club.

Dog on Tube

I still have an entire collection of Maira Kalman’s Max books—the same ones my husband read to our daughter when she was a child. And Kalman’s recent work, such as The Principles of Uncertainty and The Pursuit of Happiness, is so important to me that I bought multiple copies to give as gifts..

After Gregory’s death in April 2007, I could barely read a book—until The Principles of Uncertainty was released that October. It made me laugh and cry. Maira’s husband and design partner, Tibor Kalman, died in 1999 at the age of 49, after losing a four-year bout with cancer. How could Maira go on without him? How will I go on without Gregory?

On a page illustrated with a blue rabbit wearing red-striped socks and brown lace-up shoes, she asks, “What can I tell you?” The rabbit looks stunned, in shock, as though he has just realized something he’d rather not know. Kalman writes:

The realization that we are all (you, me) going to die and the attending disbelief —isn’t that the central premise of everything? It stops me dead in my tracks a dozen times a day.”

I’d known this already, of course, but until Gregory died, I didn’t truly believe it. Now it was all I thought about. I looked at people on the streets and wondered if they knew that they’d die, and, if so, how could they be so carefree?

Kalman shoots back:

Do you think I remain frozen? No. I spring into action. I find meaningful distraction.”

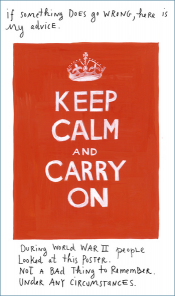

She was one of the first to bring the British World War II poster “Keep Calm and Carry On” to readers in this country. Kalman includes it toward the end of The Principles of Uncertainty, having added her own text:

If something does go wrong, here is my advice. During World War II people looked at this poster. Not a bad thing to remember. Under any circumstances.

Its sentiments seemed to describe my situation so well that I bought the original art used in the book from Kalman’s dealer in New York City.

I also bought a 2005 Kalman gouache, “Dog on Tube.” It features two women, very-very British, on the London Underground. One is young, in her twenties, and she holds a floppy-eared terrier. She has a jaunty green bow in her hair and red lipstick on her tiny mouth. She’s daydreaming, oblivious to the older woman beside her, who’s clearly irritated by the sight of a dog on the Tube. This woman clutches a tiny black evening purse in her gloved hands. But mostly, it’s her hat you notice—straw, with a wide brim and a red band and bow—and her twisted scowl. In contrast, the young woman and her dog are happy, on a journey together.

This picture is above the dresser in my bedroom. It makes me smile. Soon after my husband died, I bought a piebald dachshund and named him Mr. Henry Longfellow. He goes where I go. We are partners. Sometimes we get disapproving stares like the one in my painting, but we couldn’t care less.

Once when I was out with Mr. Henry Longfellow in New York City, a child asked his parent, “What’s that dachshund doing wearing a dalmatian suit?”

Maira would love this! I told myself, fancying us as kindred spirits. She and I are alike. We observe people we see on the street. We find meaningful distraction.

When Kalman spoke at the Westport, Connecticut, library in March 2011, I was in the front row. After speaking, she signed books. I approached, told her how much I loved her work, and asked about the story behind the gouache I’d purchased, “Dog on Tube.”

“What dog?” she asked.

“In London, on the Tube,” I said. “With the two women?”

She had piles of books to sign and seemed completely uninterested in the dog and in me. I felt mortified and wished I could disappear.

Never again, I vowed, would I try to meet one of my idols.

Slouching Towards Joan

But not too long after, I met—or almost met—Joan Didion.

On October 6, 2011, there she was, in person, at the Apollo Theater in Harlem. She was sitting across the aisle from me, arm in arm with my friend Susanne.

Seeing her came as a jolt. Could it really be Joan? And how did Susanne know her?

The event at the Apollo was the premier of Sing Your Song, Susanne’s film about Harry Belafonte and his role in the civil rights movement. It turned out that Susanne not only knew Joan, she’d been to her book-filled, cavernous apartment on the Upper East Side.

Susanne had also made a film with Joan’s nephew Griffin Dunne of Joan reading from her latest book, Blue Nights. This film was to be shown at Symphony Space the following month. Joan would appear onstage with Griffin after the screening, when they’d carry out a free-form conversation about their shared history.

Susanne had also made a film with Joan’s nephew Griffin Dunne of Joan reading from her latest book, Blue Nights. This film was to be shown at Symphony Space the following month. Joan would appear onstage with Griffin after the screening, when they’d carry out a free-form conversation about their shared history.

In November, the Symphony Space event was sold out, with a long waiting line in front. I felt like a VIP in the third-row seat that Susanne had secured for me. I looked around and saw dozens of women who looked just like me: in their fifties and sixties, with eyeglasses and short hair, no doubt English majors, writers, and teachers. I felt at home with this crowd, though there were also younger people, in their teens and twenties. How wonderful! We all adored Joan Didion, the “writer’s writer.”

Didion herself was tiny, pale, and frail on the huge stage at Symphony Space in her cashmere sweater and shawl. Now in her seventies, she talked about not being well and people being worried about her. I was worried, too. I knew she had aged, but she did not look good. She looked like she would rather not be there.

Her answers to questions from the audience were curt and often came across as dismissive. But what would you expect from Joan Didion? Gushing and dishing and pandering to her fans? The fact that she was even on a book tour—after losing her husband and then her daughter—amazed me.

As other audience members lined up at a microphone, I felt my heart thump in my chest. I thought of what I wanted so badly to ask her: Was it worth it, all those years of writing? Does it make up for the people you’ve loved and lost? Can you heal me from my own loss?

“I wish I could, Liz,” I imagined Joan answering in her breathy voice. But she would look at me kindly. She would understand. She might be curt with people who asked about the color of the pens she used or if she had a regular writing routine—but with me? No.

“Do you want to meet Joan?” my friend Susanne asked.

By then, Didion was signing books after the screening. I was tempted, but only for a few seconds. No, I did not need to meet Joan. Out of respect for this unwell woman, I would give her one less book to sign, one less hand to shake.

I had turned down my opportunity to meet Joan Didion. Would I regret it one day?

“What I Want and What I Fear”

I began this piece by referring to Maira Kalman and Joan Didion as “fallen idols,” but neither of them has really plummeted in my esteem.

Kalman continues to make me laugh, and whenever I walk Mr. Henry Longfellow in the city, I think of her. Didion remains the one writer I can turn to year after year and discover something new. I collect first editions of books, and I have all of hers. I especially love the covers of her early books, designed by Janet Halverson—Play It As It Lays, The White Album, The Book of Common Prayer.

Kalman continues to make me laugh, and whenever I walk Mr. Henry Longfellow in the city, I think of her. Didion remains the one writer I can turn to year after year and discover something new. I collect first editions of books, and I have all of hers. I especially love the covers of her early books, designed by Janet Halverson—Play It As It Lays, The White Album, The Book of Common Prayer.

My idols have given me their work; it’s not fair to expect them to be my soul mates. Let them remain on their high perches. I’ll continue to read them, listen to them, admire them—but from afar, at a respectful distance.

In her 1976 essay “Why I Write,” Didion notes:

I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means. What I want and what I fear.

In other words, she’s not my self-help guru. She writes to live, to save herself—not to save us.

Publishing Information

- Leon Wiesteler, “Voluminous,” The New Republic, February 22, 2012.

- Maira Kalman, The Principles of Uncertainty, Penguin, 2007.

- Joan Didion, “Why I Write,” New York Times Magazine, December 5, 1976.

Art Information

- Photo of Maira Kalman at the 2010 Texas Book Festival, Austin, Texas © Larry D. Moore; Creative Commons license

- Image of "Keep Calm and Carry On" poster courtesy of Elizabeth Titus; used by permission

Elizabeth Titus has been a journalist, an English teacher, an advertising executive, a communications director, and a freelance writer.

She is currently taking classes at the Sarah Lawrence Writing Institute and serves as a mentor for the Afghan Women’s Writing Project.