By Fred Setterberg

This is an excerpt from Lunch Bucket Paradise: A True-Life Novel from Heyday. Don't miss Fred Setterberg's companion essay in TW: "What's a True-Life Novel?"

Every Wednesday evening, right after dinner, Boy Scout Troop 623 devoted a full half hour to drills and maneuvers.

Inside the empty, echoing barracks-green lunchroom of Ulysses S. Grant Junior High School with its thirty-foot ceiling, we ran wind sprints over and over and over again under the pale milky glow of halogen light until we dropped to our knees and wheezed.

We slapped above our heads our soft and flabby hands that had seldom held a rake or hammer, never mind a map, compass, or rifle, dispatching a barrage of manic, slapdash jumping jacks.

We recited Scout oaths in allegiance to the Antelope, Bobcat, Moose, and Indian Patrols with the whooping rhythm of Parris Island Marine recruits—preparing us all someday to parachute behind enemy lines as fledglings of the OSS. Then crisp orders barked out from the back of our formation and we hoisted the American flag up a ten-foot pinewood pole, transporting our nation’s colors endlessly back and forth, back and forth across a generous expanse of high-gloss, crud-brown, hard-waxed linoleum. The scent of floor polish, boys’ sweat, and the janitor’s vodka-perfumed pipe tobacco filled the room.

After the drills followed a period of exercise, with myriad opportunities for distinction. In the center of the floor, match-slender Nicky LeRoux executed a half-dozen one-armed push-ups while the rest of us gathered around to scrutinize the throb of his knotty triceps. Rotund and round-bottomed James Thuggleborn proved the ideal anchor for a merciless game of tug-of-war. The temperature climbed and the lunchroom grew clammy and rank. We panted and we gasped. My own uniform sprouted soggy half-moons at the armpits while warm rivulets trailed down my back. I chanced a furtive glance at the fat eye of the wall clock: 7:20. The worst still yet to come. Finally, Lloyd Barnes, our scoutmaster, hollered for us to halt. Time for inspection.

After the drills followed a period of exercise, with myriad opportunities for distinction. In the center of the floor, match-slender Nicky LeRoux executed a half-dozen one-armed push-ups while the rest of us gathered around to scrutinize the throb of his knotty triceps. Rotund and round-bottomed James Thuggleborn proved the ideal anchor for a merciless game of tug-of-war. The temperature climbed and the lunchroom grew clammy and rank. We panted and we gasped. My own uniform sprouted soggy half-moons at the armpits while warm rivulets trailed down my back. I chanced a furtive glance at the fat eye of the wall clock: 7:20. The worst still yet to come. Finally, Lloyd Barnes, our scoutmaster, hollered for us to halt. Time for inspection.

We lined up by Patrols. I stared up at the ceiling. The acoustic tiling was riddled with a million holes the size of BBs. I silently ticked off their number, imagining that the scope and ambition of my project would render me less susceptible, but Mr. Barnes found me anyway.

“Scout, your neckerchief is crooked."

"Yes, sir."

"What are you going to do about that, Scout?"

"Straighten it?"

"You certainly will."

Mr. Barnes moved down the line. His Florsheims glistened like anthracite. I released my breath.

"Scout, your shoes are shined."

Nicky LeRoux gazed down at his feet.

"I guess."

"That's an outstanding shine."

"Uh, thanks, Mr. Barnes."

"Outstanding."

And next.

"Scout—what's this?”Our scoutmaster’s eyeballs spooled, aghast at the travesty set before him. He jutted his chin out fiercely and nodded at each of our four patrol leaders, cuing their attention. “Scout, I am very, very disappointed in you."

"Why, Dad?"

"Give me twenty! Boy, your left breast pocket is unbuttoned.”

Phil Barnes swatted his khaki jersey and grimaced. Then he dropped to the floor and began to push up and down like a piston. A batten of stage lights cast his bloated shadow on the far wall. In gloomy silhouette, Phil looked as powerful and duplicitous as Clark Kent.

"That sound about right, Ed?" blustered Mr. Barnes, pivoting on his heels to address Mr. Ortiz, our assistant scoutmaster. Mr. Ortiz sat in his folding chair at the rear of the auditorium, staring into space, bored out of his mind.

"I don't care, Barnes. If you gotta."

"He should be setting an example for the other boys, shouldn't he, Ed? Mister," said Mr. Barnes, folding himself at the waist to peer into Phil’s crimson face and bark orders. "You better grasp that if you plan on becoming an Eagle Scout, you don’t walk around with your shirt pocket unbuttoned. Do you understand me?"

"He's doing fine," said Mr. Ortiz, shaking himself to attention. "Can't you ever leave the kid alone?"

Endless inspections would have driven all of us out of the troop, except for the promise of overnights. Every other month, we camped out in the desert, the shore, the foothills close to home. Mr. Ortiz usually came along, sometimes my father, too. The men relished the time spent talking around the flickering light of the campfire about growing up close to the woods, the trout they always brought home as boys for Sunday dinners, the stags and wild turkeys that got away. Dad got on well with Mr. Ortiz, who was not drawn to scouting for the drills and discipline—even less for pitting the Moose Patrol against the Indian Patrol in a contest of fern identification, or worse yet, for inducing the Bobcat to collaborate with the Antelope to produce a campfire banquet of Spam and foraged miner’s lettuce. Mr. Ortiz preferred to shoot ducks, sleep under the stars. He had served at Guadalcanal; he didn't want to talk about it. Lloyd Barnes idolized this reticence, but he could not emulate it.

Our patrols disintegrated, and one by one we looped into a large circle, bowing our heads in preparation for the closing prayer. But first, Mr. Barnes had an announcement. Two new Tenderfeet would be joining us for the overnight. Girlish chatter rippled around the circle, and we temporarily broke ranks, even our patrol leaders snickering like third graders over the evil-genius initiation rites that we would subject the newcomers to on Frog Island. Then Mr. Barnes nodded to Mr. Ortiz who opened the auditorium side door and whispered into the hall.

"Don't be shy, boys," Mr. Barnes called out vigorously. "Come meet your new friends."

Two teenagers slouched across the threshold. They were ridiculously old to be Tenderfeet, perhaps sixteen or seventeen. The tall one wore crumpled blue jeans and a white t-shirt with the front pocket stretched into the shape of a pack of Camels. His sallow complexion and caved-in chest indicated poor nutritional hygiene and a pitiless indifference. The other kid was bull-necked, smirking, clad in a white ruffled dress shirt, his blue jeans split six inches up the cuff with the seams extruding red velour. A towering blond wave rose from the crown of his skull like a petrified tsunami.

"Boys, introduce yourself to the troop."

The two teenagers glanced at each other, and then the scrawny weasel boy stepped forward, clicked his heels, and elevated his right arm in the Nazi salute.

“I am Rommel of the Desert, herr commandant. General Rommel.”

The other one slugged his shoulder. "Don’t lie, man.”

“Hell, no!” whooped weasel boy. “I’m Henry Eagle!"

"No, I'm Henry Eagle.”

“No, I’m—“

"Young man," Mr. Barnes informed him patiently, "your name is Ralph. Ralph Studge."

"Oh, that's right. I'm Ralph Studge. Don't nobody laugh. And this here is Henry Eagle. Maybe you heard of him. Say hello to the nice boys, Henry."

Ralph Studge had not fooled me. Although merely a freshman, I had personal knowledge of Henry Eagle, our high school's leading delinquent, a second‑try junior, a boy shaped like a refrigerator and inclined to felonious assault.

I had met Henry in first-period General Math, where we shared a desk on those irregular occasions when he was not residing at Juvenile Hall. Since Henry shouldered the responsibility for maintaining our school's high standard of statutory offense, he did not always have the leisure to complete his homework or even vaguely acquaint himself with the general direction of his own education. Fortunately, he was willing to accept my answers to every exam, and on Monday mornings, as a reward, he summarized for me his weekend activities.

"I got arrested again."

"Ah, that's too bad."

"I don't mind. I hit a cop. See?” He thrust a freckled fist under my eyes, displaying the teeth pocks. His thumb and forefinger were yellowed from nicotine. He smelled years older than the rest of us. “You ever been arrested?"

"Ah, no. Not really."

"You're young still. You got time. Gimme your homework."

Now Henry Eagle stood at the front of the lunchroom in Ulysses S. Grant Junior High School, and as the overhead halogens rained down a flood of insipid pale beams, he bowed at the waist in mock surrender to Troop 623. He held the bow for several moments too long, and I wondered if perhaps he had gotten stuck. My eyes shifted around the room to our four patrol leaders. Nobody volunteered to help.

"Right," said Henry, gradually rising vertebra by vertebra to meet our incredulous stares with a nasty little scowl. "That's right, I know who everybody is now. And hey, we're really glad to meet all you Boy Scouts."

• • •

My father had just finished reading a biography of Millard Fillmore and was moving on to the life of Rutherford B. Hayes. As a young lawyer, Hayes had concocted on behalf of a deranged murderess an elaborate insanity defense, one of the nation's first. Citizens regarded the tactic as ingenious, but despicable. Ninety years later, my father sat in his green Naugahyde La‑Z-Boy recliner in the corner of our living room and complained in a complementary vein that our neighbors knew so little of the Republic's foundations that they could not distinguish Rutherford B. Hayes from James Garfield, or Garfield from the craven and corruptible Chester A. Arthur.

"Hayes is the one with the beard," I told my father.

"What kind of beard? I want to remind you that Garfield's got a beard. Grant, too, of course."

"The whiskers come down to the top of his chest."

Dad settled volume H of the World Book Encyclopedia in his lap. He was making the best of Sunday evening following an argument over something that had driven Mom out to tend the backyard clothesline. I sprawled across the carpet, soaking up his undivided attention. On the other side of the living room’s picture window, the patio fountain splashed and burbled. Mountain lions or vultures or more probably our neighbor’s cat had recently been scooping out and devouring our pond’s Rexall goldfish.

"What color?" demanded Dad, flipping to the relevant page.

"They only had black‑and‑white photographs back then."

Dad stared darkly at the photos, sizing up their sorry limitations.

"God, I don't know. Grey."

"Then what does that tell you?"

"That Rutherford B. Hayes was the President with the long grey beard. Not those stupid white sideburns. Those stupid sideburns belonged to Chester A. Arthur. They named my elementary school after him."

"Chet Arthur, who kissed Roscoe Conkling's ass—that's correct."

Dad flipped shut the encyclopedia. "All right, then." He reared back in his La‑Z-Boy. "Here's one for you, smart guy. Mr. Teddy Roosevelt!"

"The only President to have shot an elephant."

Dad nodded appreciatively. He extracted his pipe from his front shirt pocket, stuffed it with pouch tobacco, and fired the bowl with a single match. "Your turn."

I thought hard for a moment.

"Buchanan!"

"He never married," said Dad firmly, "and the man had no family. Not to mention he pretty much instigated our Civil War. What about Polk?"

"He fought the Mexicans."

"I guarantee you," replied my father, leisurely puffing on his pipe, "that he didn't do any of the fighting or the bleeding or the dying. Half a point." Then a beat later: "Lincoln!"

"Had a big black beard, but no moustache."

"Every Tom, Dick, and Harry can see that."

"Freed the slaves."

"Oh, good Lord!"

"His kids were dead, and his wife was crazy."

"All right," said Dad, settling back into the curve of his recliner, relishing his authority and adjusting his bifocals before immersing himself in Rutherford B. Hayes. "I guess we can agree about that for now."

What was worth knowing? This question confused me lately. Was it more important for a young man to know how to swing an axe and navigate by the stars—or be able to name each member of FDR’s Brain Trust under the direction of Rex Tugwell? I could only hazard a series of estimations, moving from one to another of the puzzles Dad routinely set before me.

What was worth knowing? This question confused me lately. Was it more important for a young man to know how to swing an axe and navigate by the stars—or be able to name each member of FDR’s Brain Trust under the direction of Rex Tugwell? I could only hazard a series of estimations, moving from one to another of the puzzles Dad routinely set before me.When the doorbell rang, I sprang to my feet, first by a mile.

“Well, say hey there, Little Slick!”

Win flicked the screen door handle like a pinball lever and eased himself inside. He grinned at me with that moon-in-his-mouth smile, wiping his feet cautiously on the throw rug and then examining Dad to see if he had appreciated the effort. He had not. Win smelled of Old Spice and a recently extinguished cigar. I figured there was probably some trouble again between him and Aunt Tina. I couldn't count the number of Sunday evenings when Win arrived at our house with time on his hands. He slapped me on the back like we were old pals, which I believe we were.

“Hello, Win.” My mother drifted in from the back bedroom, her hands encircling the girth of a yellow plastic laundry barrel. “Is everything alright?”

“What’cha all watching?” Win nodded at the television set. The screen was blank. Dad held up his presidential biography, snorted, and returned to the page.

“Bonanza’s at eight,” said Win. “Should I turn it on?”

“Sure,” I answered.

“No,” said Dad.

“I’m going to call Tina,” offered Mom.

“Aw, she’ll be fine, Sis. Just give her a chance to cool off.”

“Stay out of it,” ordered my father. “Let him clean up his own mess.”

“Nothing to worry about,” muttered Win. He crouched at the foot of the TV console, bashed the power button, twirled the channels. The camera panned the Ponderosa—Ben Cartwright's endless spread of priceless ranch land just over the border in Nevada.

“Don’t you got homework?”

I dashed into my bedroom. Returned with a library book. Settled down to study and watch Bonanza. The puzzled face of Hoss Cartwright roved into view, occupying the entire screen. When Little Joe appeared, Mom joined us on the tufted sofa chair positioned within shouting distance of my father. I set my book between my knees and flipped a few pages.

“What are you reading, dear?”

Win turned up the volume so we could all hear now. "Mom, you wouldn't be interested."

"I might."

I was fourteen years old. Already confirmed by the Catholic Church as a Soldier of Christ. In three years I could buy cigarettes—even join the Army if I wanted (as long as I had my parents’ written permission, according to Nicky LeRoux). What I read, as Dad would say, was my own business.

“Tell your mother!” said Dad.

"It's about history."

"Show me the cover, dear.”

I slid my library book across the end table. It was a lap‑sized survey of ancient Crete borrowed from school. The ancient civilization of Crete was a subject that intensely interested me these days because according to the highly detailed color illustrations evident from the first few pages, the women all walked around naked from the waist up.

Win snickered into his hand and leaned across the couch to clap me between the shoulder blades. He was himself a devoted reader of Stag. I had borrowed the latest issue to read about the Lustful Leopard Girls of Burma.

"Ancient civilizations," I explained cagily. "It's what we're studying now."

"He's studying naked ladies in school," corrected Win, addressing Hoss Cartwright on the TV screen. "Slick, ain't times changed?"

Dad regarded the book jacket’s feeble promise: Crete: A History. “I'm going to turn off the squawk box right now," he said, "so we can all read in peace." He tossed a copy of Life at Win's feet. The cover featured Cassius Clay beating the brains out of Sonny Liston.

"What about you?" Dad demanded, glaring at me as he clicked off the television. "You got any real homework?"

"I want to watch Bonanza with Uncle Win."

"No, you don't."

“Study your Scout book," suggested Mom, "and you can earn some more merit badges."

"I'm quitting Boy Scouts."

"Wrong," explained Dad. “You’re not.”

"Scouts can teach you your way around the woods," said Win, sinking into the sofa folds. He peered thoughtfully out the picture window at our burbling fountain and the shoulder-high hedge of golden junipers, their sentinel bulk arrayed in the increasing darkness like a detachment of Praetorian Guard. Eventually he would have to return home and face the music, but there was no sense rushing it. When my father settled back into his chair, Win figured he had earned another half hour's stay. "Your grandfather knew his way around the woods," Win told me. "Didn't he, Slick?"

Dad grunted assent.

"You remember the ol' man?" asked Win.

"He died when I was just a baby.”

"Hell, I remember the ol' man. What a son of a bitch."

"Win," cautioned Mom from behind The Saturday Evening Post.

"I wouldn’t tell a lie, Sis."

"Read," ordered Dad.

"I'm too old to be a Boy Scout!"

"Well, if you want, you can bleach out those oil stains covering the garage floor."

"I don't even like to hike!"

“Isn’t your friend Philip still a Boy Scout?”

“Mom, Phil’s a leper.”

It was true. But for now, he was still my best friend.

“Leopard?”

"And I've still got about two hundred nuts and bolts under my workbench that need sorting."

"All we ever do is march around. It's like the Army."

"You could always do the ironing for your mother so she doesn't have so much tomorrow."

My eyes flipped back and forth between Dad and Win, spotting no sympathy or assistance from either quarter. "I'm going to read about merit badges," I announced. The notion really did seem to originate from my own bright and lively imagination. I rooted through the stack of newspapers in the wire reading rack at Dad's side and eventually found my Boy Scout Handbook at the bottom.

When you are a Scout, I read silently to myself from the first chapter, forests and fields, rivers and lakes, are your playground. You are completely at home in God's great outdoors....

• • •

I dreamt of Alma Ardilla. Her flat face and bulging white teeth flitting past like an Aztec war mask. Her sable tresses tied in a bun and coiled at the top of her skull like a bird’s nest. Alma’s wobbly spindle brown legs, her webbed fat feet squeezed into too-small red peep Confirmation pumps. Her thin, slack shoulders wrapped in the same kind of front-buttoned short-sleeved Sear’s white dress shirt that she and her brother Teo had been wearing every day since elementary school. In my dream, Alma bared her teeth, raised her chin and sniffed at my face, no longer the shy, sad, mute little girl I had known since First Communion class. Her brown eyes pooled, her black pupils swelled and pulsed. In my dream, Alma clipped her fingers at the corner ends of either collar, slowly drew her hands six inches apart, and button by button plucked open her flimsy white shirt from the throat to her brown belly—astonishing.

That’s always when it happened: me bucking and flexing beneath the sheets, waking with a gasp, my eyelids collapsing in a ruthless desire to catch one last glimpse of Alma’s bare plain of copper skin, the spectacle of her tiny nipples more guiltily imagined than seen—and then the soppy, warm, sticky realization that whatever had transpired down there at the erupting hot crook of my imagination, the mess was already coating my thighs and saturating the sheets.

Phil and I ardently discussed the theoretical pleasures of young women. How Merrie Banderas bobbled her hips in the hallway, unconscious of the devastation wrought among us. The bulbous, bouncing riches contained within Karol Kowalski’s stingy blue cotton sweater. The way Mademoiselle Derain’s small pink tongue darted out to moisten her lower lip when either of us dared an imperfect verb conjugation at the front of her classroom, our teacher’s mouth pursed in mock disapproval and forming a perfect wet red circle that hinted at expert French joys for her husband.

Yet Phil and I never talked about what was actually happening in our ordinary lives of failure among the girls we actually knew. How I had longed to ask Gretel Pell to slow dance with me on Friday nights when the last tune before the lights came up was always Gene Pitney’s “Town Without Pity.” How finally I had traipsed across the Death Valley of our school’s multipurpose room floor, asked her, and then turned around to retrace my steps across a much vaster Sahara when she refused, taking my rightful place next to Phil, a leper, who patted my back and advised me to forget her.

How Phil stammered in the company of any girl he liked. How sometimes in their vicinity he excreted an odor reminiscent of smoldering Nylon. How last year he had stood at the front of our eighth grade Social Studies class after volunteering to be the first to recite the mandatory preamble to the Constitution only to discover as Angela Bonaire whinnied and neighed in the front row that his barn door was wide open.

As manhood loomed, new challenges had arisen and the talents I once prized in my closest friend—his facility with his Gilbert chemistry set’s Bunsen burner and Pyrex beakers, his command of all the names of the Luftwaffe high command (Oberkommando der Luftwaffe, Phil corrected pedantically)—would not help us to prevail. My boyhood best friend was becoming a liability.

His impetigo blossomed, trimming his lower lip and drooping across his chin like a scrofulous ruby goatee. He wore his Boy Scout uniform to school, deaf to the ironic queries of sophomore girls who recalled their own childhood stints as Bluebirds. Phil would plead with me to wait for him after school, even though I negotiated the most roundabout route home to avoid our new classmates’ scrutiny—a maneuver that Phil wretchedly believed was intended to prolong our time together. And once—no, more than once—when Phil and I were joined on the way home by Nicky LeRoux or Benny Chang or even the Chestnut brothers, who were wildly unpopular due to their loquacious Kentucky drawls and their identical bad complexions of ten thousand blackheads, we all conspired to ditch my old friend at Porter’s Market when he dipped inside to purchase a sack of Brach’s candy corn. As we hurried around the corner, I saw Phil standing there, switching his head back and forth like Burgess Meredith in that episode of The Twilight Zone when, having been locked inside an underground bank vault during an atomic war, he finally stumbles outside to find himself excruciatingly alone. Where’d everybody go?

• • •

By 6:30 AM, most of the troop had assembled in the parking lot and squeezed into Mr. Ortiz's Oldsmobile and Mr. Heilborn’s Buick. Mr. Ortiz took off first, hammering out a farewell shivaree with alternating fists on his car horn and gassing it hard so that all eight cylinders snarled and spat as he rumbled down the block. Mr. Heilborn followed closely behind, permitting several Scouts to snake their worm-boy torsos out the passenger seat windows and bay pointlessly at a remaining sliver of pearl moon. I stood in the parking lot with Phil and Mr. Barnes, waiting for our two new Tenderfeet. A heavy lid of kettle-grey sky settled upon the rows of peaked rooftops. High above a few stars still flickered. Still, it felt like an adventure to be up and out in the world so early. It felt full of promise about the things men do on their own.

For the next fifteen minutes, Mr. Barnes paced silently back and forth in front of his Rambler. Phil fixed his dead eyes on the blank wall of the nearest classroom. I stared at the toes of my black high-top Keds, sensing that we were all supposed to be in mourning about something or other. Finally, I glanced up and spotted Henry and Ralph dragging themselves into view—each cupping a cigarette in their retracted talons, passing back and forth the brown‑bagged dregs of a twelve ounce can of Olde English 800. Henry had confided to me more than once in General Math that he was a morning drinker.

Mr. Barnes bawled them out, employing copious references to letting down the whole troop, chains only being as strong as their weakest links, the mortal necessity of unit cohesion under enemy fire. The Tenderfeet looked baffled. Following our scoutmaster’s orders, they shouldered up the Army surplus backpacks borrowed for them earlier in the week and staggered for an instant under their heft. Mr. Barnes looked pleased.

We fit all our packs in the back of the Rambler station wagon, climbed in, and hit the road. I balanced on the backseat hump between Henry and Ralph. Phil rode shotgun. Mr. Barnes switched on the AM radio to catch the weather forecast, followed by the farm report, both of which seemed to cheer him up. Scouts, he explained, should strive to acquire precisely this kind of information. Henry and Ralph glanced at each other, perplexed.

"Are we really going to sleep outdoors?" Ralph asked as we sailed down the greased‑clean empty freeway. It felt like we were explorers at the edge of the known world.

"Of course, son."

"Haven't you ever been camping before?" wondered Phil.

"No."

"Me neither," admitted Henry.

"You'll like it," I offered.

Ralph popped his balled‑up fist into my solar plexus. I gasped for breath.

"What about animals?" demanded Henry. "Bears and shit. We taking along a shotgun to protect ourselves?"

Mr. Barnes laughed like he thought he was supposed to do in order to establish esprit de corps. "There're no bears where we're going. And remember, son: Scouts don't swear."

"Christ, where are we going?"

"Or blaspheme," clarified Mr. Barnes. "We're heading to a little place on the delta called Frog Island. There'll be swimming and races, and you boys'll definitely get a chance to do some map and compass work."

We approached the Carquinez straits. The Rambler rattled across the bridge and passed quickly through the toll booth. Nobody was on the road weekends.

Ralph grabbed my skull in a headlock and squeezed hard, pulling my head down into his lap.

"Hey!"

“Faggot! Quit trying to bite me!” Ralph thwapped my skull with the flat of his hand. “You see what this faggot did?”

"Boys!" erupted Mr. Barnes, whipping around for a perilous instant to peer into the backseat. "Last warning. No roughhousing 'til we reach the woods. Then if you still have a disagreement, we can put on the boxing gloves and solve it like men."

"When we reach the woods," Ralph whispered into my ear, "I'm going to pop your head like a pimple."

"Why?"

Ralph smiled and shrugged good‑naturedly. "Dunno."

Several miles rolled by all too quickly. I kept my eyes straight on the road. Mr. Barnes turned up the radio and hummed along with Percy Faith's “Theme from A Summer Place.”

"Hey, Henry," I asked, hazarding a glance at my occasional classmate, aiming to renew our alliance and gain a measure of protection from Ralph Studge. "Did you go to the football game Friday?"

"Nah, we was in Juvy. Who won?"

"They did," I had to reply, but that wasn't really my point. Warren G. Harding High School never won. Winning wasn't something our team got involved in. But we had tried hard. Maybe that was my point.

It had been an exhibition game at the very beginning of the season, with Harding playing a small private school from somewhere in the Oakland hills near Piedmont. The private school was full of the sons and daughters of doctors and lawyers, dentists and architects.

Before the kickoff, our marching band had wandered onto the playing field, the trumpets breaking into pig squeals on the high notes, the cymbals crashing persistently off the beat, the clarinets squeaking and striding into the end zone like the lost and the blind and the deaf. People in the grandstands were laughing through “The Star‑Spangled Banner.”

Yet by some miracle, our football team, renowned for its unbroken losing streak extending five consecutive seasons, inexplicably found itself ahead at halftime by a single field goal. The crowd on our side of the stands was delirious, we could smell victory, it was so sweet and rare. Then the rich kids' cheerleaders ordered the crowd on their side of the bleachers to rise, which they all did with quiet, disciplined unit cohesion, and the song girls led them in an impromptu cheer that we had never faced before.

They cheered: "HEY, HEY, THAT'S OKAY, YOU'RE GOING TO WORK FOR US SOMEDAY!"

Then their team ran all over us throughout the second half.

"Actually, it wasn't a very good game anyway," I suddenly remembered.

Ralph drove his knuckles into the soft spot right above my kneecap. Hard.

As “Theme from A Summer Place” concluded, Mr. Barnes mercifully stopped humming and nudged Phil several times until he finally swiveled around to face the two new Tenderfeet.

"So," Phil asked without a flicker of genuine curiosity. "How did you get interested in Scouting, Henry?" Henry sat picking his teeth with a long filthy thumbnail. "The judge," said Ralph. "How's that?" I asked.

Henry honored me with a cursory glare.

"The judge said we could join the Boy Scouts or go to California Youth Authority. We flipped a coin, and you guys won."

Mr. Barnes struggled with himself not to say anything. He lost.

"Boys, both Henry and Ralph have been remanded to the Scouts by the juvenile court. The judge thinks maybe we can make men out of them. Young braves. Teach them the meaning of responsibility."

"What'd you guys do?" I asked.

"Stole a car."

"Murdered my brother. And also my mother and father."

"Don't get smart, boys."

"Smoked them motherfuckers!"

"Boys!"

A pause. Ralph Studge sighed and stared out the window. We passed the refineries, the naval base, the new suburbs chewing up the flaxen-haired hills. The world was the most boring place imaginable.

"We didn't do none of that stuff," he confessed.

"Nope, we're innocent as hell."

"Going to be Boy Scouts," sighed Ralph.

“We’ll make a regular Lewis and Clark out of you two,” Mr. Barnes assured them.

Ralph’s poxy complexion brightened.

“The dude’s named Louis? Sounds like a faggot.”

“Two men, boys. Young Bill Clark and his companion Meriwether Lewis. Our national Corps of Discovery.”

“Meriwether!”

“Two faggots!”

Mr. Barnes glanced into the rearview mirror and forced himself to smile. He was not positive that he liked what he saw.

"Dot‑dah, dot‑dah, dot‑dah," said Mr. Barnes. "Dah, dah, dah!" He droned on in a nasal, electrified hum. "Who wants to practice their Morse code?"

• • •

What made the popular kids popular?

Football players were obvious recruits for the in crowd. At least, the backfield. A tackle or guard had to insinuate himself by other means. Say, a ’59 flat-black Ford jacked up three feet high on hydraulics with an eight-track booming “Sugar Shack” by Jimmy Gilmer and the Fireballs as his calling card. That worked for Elbert Graff, a gobbling oaf who once pantsed Benny Chang as he innocently stood on his number out on the P.E. blacktop in the middle of winter. (This automotive stratergy could work to cross purposes, too—as with Ted Parina, a doleful senior with a pepperoni complexion, no achievements, and an A-uuuga car horn signaling his arrival that only drew attention to the fact that nobody cared.)

Cheerleaders clearly belonged. They even did their own sorting, making room for Panda Quilby, an otherwise unsuitable, too-tiny, figureless, dishwater brunette who bumbled, pitched, and toppled to the ground every time our marching band launched into its up-tempo and off-key rendition of “Semper Fidelis.” The squad stubbornly deemed her “cute,” and who could argue with them?

Hard cases fell into a subspecies. Henry Eagle strutting late into Auto Shop, his Juvenile Hall t-shirt yellowed at the armpits, his two-day stubble looking all the more sickening for being soft and blond like the lanolin threads of a shaving brush. This was not the face of budding In-Crowd insouciance and poise. Still, they granted him recognition as an object of alarm, best tolerated until the bell tolled and Henry’s time, too, came for the Army, prison, or death by helmetless motorcycle mishap.

The in crowd was blessed with superb timing.

Bottom kids were easy to identify. Everybody knew who they were, though they sometimes, amazingly, did not. Oblong, freckled, clumsy, nearsighted—and let’s face it—stupid Allan Allwater ensnared himself in perpetual ridicule one day in art class by plummily singing to himself:

"Don’t play with me 'cause you’re playing with fire…."

Randy Motram’s mother washed his gym clothes with a scarlet towel, dyeing Randy’s jockstrap pink: branded forever. Arnold Hines was thirty pounds too fat so some hard cases stripped off his sweatshirt when he wrestled equivalently porcine Bobby Degas, their bellies rippling and rolling, crashing into one another’s in bucketing waves of nauseating gristle and lard. Unforgivable. Guaranteed to be beaten, belittled, tripped in the hallway, dunked in the boy’s bathroom toilet, backhanded and headbutted on the perilous trek home, labeled spaz, retard, maggot, faggot, creep, leper, goon, dip, dork: the uncoordinated, the unconfident, the ridiculously small or farcically tall, the ever-studious and blatantly dumb, bed wetters, crybabies, anybody donning a leather jacket and sunglasses without sufficient aggression and indifference to pull it off. Anybody whom anybody else regardless of their status could successfully label a spaz, etc., without bloodshed or consequence.

I prayed to Jesus, pleaded with God, beseeched the Holy Spirit to never let me wander into this category of the damned.

Certainly not to keep Phil company.

Girls were another matter when it came to separating the winners from the losers. Girls operated according to a pattern imperceptible to boys, even the popular ones. Girls made you wonder what the rules were really all about.

In junior high, when Debbie Hamsun’s parents took the stage on Talent Night to play electric guitar and sing “Matchbox”—just released on the Beatles’ Something New—the prospects for lasting dishonor appeared staggering. Yet for reasons indecipherable to all but the inner circle of in-crowd females, the event was judged a triumph and Debbie began to walk home from school with Karen Benavides, Stacey Pastor, and Katrina Rodriquez—our school’s flat-chested, hair-ratted arbiters of deportment and style.

Taking the kind of risk that Debbie Hamsun had allowed her parents to assume on her behalf was reckless, foolish, unthinkable, stagey, sly, brilliant, successful.

Not to be repeated.

Yet overnight—certainly, over the summer—new members of the in crowd were stealthily coined. Though only a lowly freshman, Mickey Dupree ran with a pack of older cousins who taught him to smoke, drink, flirt, fight, and (or so he claimed, though Phil and I both told him to his face that we very seriously doubted it) feel up Stacy Pastor in her own living room when her parents went out on Friday night to roller derby. Mickey stayed up late to study The Steve Allen Show and at the lunch table where he sat with upperclassmen Danny Rivera, Ralph Studge, Charlie Rivers, and other marginal in-crowd soldiers and hard cases, he mimicked his master, Steverino, by intermittently and inexplicably screeching: Smock! Smock! The fourth-period bell chimed portentously. “Smock! Smock!” shot back Mickey. I just smiled and kept my mouth shut.

To the countless spies and infiltrators, the in crowd divulged nothing.

Yet already in science class, we were learning how the wolf detects her mate, how the ant locates the path winding intricately back home to the nest. Discrete, minute chemical secretions. Pheromones—which are nature’s way of saying who’s ripe for reproduction, whose body knows more than his head. You can’t fake it. It’s ready or not. We all get a whiff of each other and learn the truth.

• • •

"We're lost, aren't we?"

Mr. Barnes ignored the question. He sat on a small boulder shaped like a medicine ball, unfolded the map, and studied our prospects. His official Boy Scout compass roved over the squiggle of topography allegedly delineating our position. When the compass did not produce the expected results, he thrust it in the air and shook it wildly like some figure from the Old Testament berating Jehovah.

"A Scout is never lost!" he explained, exerting himself violently in an effort to calm himself down. We circled around our scoutmaster. For nearly two hours, we had beavered through the tall grass in a vain effort to catch up with the rest of Troop 623. A vindictive sun blazed above. The wind slapped our faces and stung our eyes. Now we sat cross‑legged alongside Mr. Barnes's boulder on the dusty patch of ditch grass and poison oak that he had mistaken for the main trail across Frog Island. The exhausted air smelled of ragweed and dragon flies.

"It's just like your Scout handbook explains," Mr. Barnes ventured tentatively, and we all perked up in expectation of a way home. "Ralph, have you purchased your Scout handbook yet?"

"'Course not."

"Henry, what about you?"

"No way."

"Well," continued Mr. Barnes, "it's just like your Scout handbook informs us. Somebody once asked Daniel Boone if he were ever lost, and the great woodsman replied, 'I ain't never been lost'"—Mr. Barnes’s stress on the crude folksiness of "ain't" signaled his own recognition of the faulty grammar, and this distinction seemed to momentarily cheer him up—"'but I have been a mite bewildered for a day or two.'"

"You saying we might not get out of here for a couple of days?"

Henry’s bulgy biceps twitched, and he demonstrated his disapproval by kicking up a suffocating cloud of dust.

"Rule number one," replied Mr. Barnes, quoting directly from the Scout handbook. "Stay calm."

"Fuck this shit," said Ralph. "Man, we should've just done six months at Youth Authority."

Mr. Barnes waved his hand in the air, trying to settle the dust and whisk away the aroma of fear and hostility rising off the two Tenderfeet.

"Phil," I asked, "where do you think we are?"

"Yeah, Boy Scout," said Henry, full of sudden hope and indignation. "Where are we?"

Phil studied the map, stood up, surveyed the skyline, raised his thumb to his eye to take the measure of a lone tall tree far in the horizon, and then he pivoted a half‑circle calculating Lord knows what. Over the past year, Phil had earned merit badges in Camping, Pioneering, Forestry, and Wilderness Survival, along with less immediately useful achievements in Astronomy and Book Binding.

"Can't tell," he concluded.

Henry smacked the back of Phil's skull, tumbling his cap into the dust.

"Don't fuck with me," he advised.

"Scouts!"

"The rest of the troop wouldn't have left without us," Phil reminded everybody, "if these two guys hadn't been late."

Phil shook the dust off his cap, resettled it on his head, and crouched close to the map. "Look, here's where we want to go. And it seems like we can cut across here"—he indicated more insensible squiggling—"and maybe pick up the trail on the other side of the creek."

"Thanks, Phil. Henry, you be nice to Phil because he's going to show us the way to get the fuck out of this place."

"We're just a mite bewildered," suggested Mr. Barnes, raising one hand over his eyes to reconnoiter the fields of yellow lupine and the towers of yarrow gone to seed and spouting like crowns of broccoli.

"If anybody says one more word about how they know their way around the goddamn great outdoors," promised Henry, "I'm going to kick their teeth down their throat."

"You boys just don't understand the woods yet," explained Mr. Barnes, deaf to sound advice. "Experience. That's what Scouts is going to teach you."

Frog Island wasn't actually the woods, and that was the problem. Frog Island was a marsh pitted with bogs, punctuated by swamp, enclosed by fen. Tule grass, toad rush, picket fence alignments of cattails and what looked to me like waist-high relatives of the basic backyard dandelion sprouted from the shoreline like patches of wild hairs on an otherwise scraped-raw and balding, dust-laden, stamped-over scalp. The few trees left standing were stumps filled with evil grey spiders and large, frisky, biting black ants. (Ralph had already found that out while removing a stone from his shoe and plopping his butt on top of their colony.) Poison oak prevailed. The pollen made everybody’s eyes water. You could detect the faint odor of skunk nearby. I didn’t understand why we had come there. It might have been an agreeable place to spend the afternoon if you were a cloud of mosquitoes, but not for two dozen Boy Scouts from the suburbs.

"Be cool, my man," Ralph cautioned Henry.

Mr. Barnes caught up and resumed command.

"Boys," he declaimed passionately, "we're going to reason our way out of here!"

Lacking an alternative, we paid attention.

"I think Phil has pointed out the sensible route to locate the rest of our troop. From the map, I'd say it's going to run us"—he consulted the map again and frowned judiciously—"what do you think, Phil, maybe a half hour?"

"Four hours."

"Between a half hour and four hours," confirmed Mr. Barnes. "Depending on our pace."

"Then get your ass moving!" said Henry. “Christ, you’re like a bunch of old ladies.”

We slogged along the marsh banks. Ducks skittered down in the distance, vanishing behind a fortress of water plantain and cattails. Our scoutmaster encouraged us to keep our eyes open for edible plants. I raked an open palm across my forehead to swab away the grime. Ralph kept prizing off my tennis shoes at the heels. The leaden air gained another ten pounds with every hundred yards we stumbled. Henry whispered into Phil's ear what he was going to do to him if we didn't find the troop campsite by dinner time.

“Who wants to sing?” shouted Mr. Barnes from the rear. “Sound off! Left. Right. Left, right, left. I don’t know, but I been told….”

Nobody picked up the cadence. We hit a dry patch on a gradual rise that blossomed into a wider grubby trail leading nowhere and bracketed by blackberry vines. Everybody broke ranks to sample the berries and let Mr. Barnes catch up.

“Hey,” Ralph asked, “you like pie?” I glanced over either shoulder. Nobody there.

“Yeah, I’m talking to you. You like pie, buddy?”

I nodded. The sudden camaraderie made me wary, but I appreciated the way Ralph didn’t punctuate his question with a slug to my guts.

“What kind?”

I shrugged. “Pumpkin?”

Ralph shook his head. “No, not pumpkin. What about berry?”

“Sure, I like berry.”

“Then have a big slice!” He placed two open palms on my chest and shoved. I fell over Henry, who was crouching on all fours behind me, and tumbled into the blackberry bramble.

Mr. Barnes finally caught up.

“Scout,” he ordered, as I thrashed about and further entangled myself in the web of thorns and bristles, “get out of there right now before you stain your uniform.”

In a half hour, we reached a small stream. Our two Tenderfeet plopped down at the edge of the sand spit, plashing handfuls of cold water into their pink sun-flushed faces. Phil detached his canteen from its belt pack, sipped moderately. I followed his example, but Ralph grabbed my canteen and finished it off. Phil motioned for us all to fall in around the map. He fingered our probable location and indicated a shortcut to the main trail. We would ford the stream for about twenty yards and then head due east over the hills.

We stripped off our packs and pressed them up above our heads as we waded across. Phil eased into the water first, balancing delicately with each step. Twice he almost slipped, skating over the smooth surface of polished stones, swishing into a deep muddy patch.

"Toss your packs to the shore," Phil hollered once he had reached the other side. "It'll be easier that way."

Mr. Barnes raised his pack to his chest and pushed with all his might, launching the load high into the air—but the weight of our troop's frying pans and cast‑iron pots sucked the pack directly into the channel, where it sank below the water line about two feet from shore.

"Too heavy," reported Mr. Barnes. His voice strained to remain pleasantly informative. Ralph sniggered. Henry cursed. Phil dragged the pack out of the water, and our scoutmaster waded across without further incident.

Henry, Ralph, and I carried our equipment across the channel. Ralph shoved me out of the way, lifted his pack over his head, and carefully retraced Mr. Barnes's steps. I followed Ralph. Henry followed me, but somewhere in the middle his legs skipped a foot or so ahead of his shoulders, and he jackknifed to the muddy bottom. His head bobbed at the water line. He cursed the Boy Scouts of America. Finally, Henry stood and dragged his pack to shore, stirring the swill.

"Gimme a towel!"

"My Dad was carrying all the towels in his pack," explained Phil, "and they're soaked."

Henry focused his eyes into rays of loathing.

We spent the next twenty minutes tramping across an expansive field of burrs and stinging nettles. Henry tripped, disappeared for a moment amid the towering sedge, and rose with an elaborate and blasphemous execration. He was flocked in the style of a miserable Christmas tree with hundreds of cottony tufts that seemed in the sudden breeze to flit directly up his nostrils. He snorted, coughed, cursed. With a groan, he stretched out his open palms to reveal a plastering of prickly spines.

"You okay, Henry?" asked Phil. His voice sounded as smooth and sweet as cough syrup.

"I'm going to reach down your throat and pull out your appendix!"

"'Cause why I'm asking," said Phil, shading his eyes as he monitored the sun’s progress, sagely nodding to himself over the probable nearness of our next calamity, "is I'm hoping you didn't pick up anything bad for you in that water."

"What do you mean, 'pick up something?' Like what?"

"Oh, nothing. Don't worry about it."

Henry shook off his burrs. He fell into line behind Ralph, and we swished into a mud patch and then back through the nettles.

"What are you talking about, squirrel‑brain? Tell me."

Phil suddenly halted. I bumped into Ralph, and he punched me in the stomach. Mr. Barnes marched slowly up the rear.

Phil suddenly halted. I bumped into Ralph, and he punched me in the stomach. Mr. Barnes marched slowly up the rear."You don't smell anything funny, do you? I mean on your own body."

Henry sniffed his wrist, worked his way up his arm. "I just fell into a fucking swamp, butt‑breath. What do you think I smell like?"

"I'm sure you're right. No reason to worry. Let's keep marching, men."

"No, wait a minute. We're not going anywhere until you tell me what's in that water."

Phil fixed his gaze on Henry. His lower lip protruded in an earnest expression of dread and compassion for a fellow Scout. "As long as you didn't swallow any, like even a droplet, Henry—then they can't usually hurt you."

Henry promised to gouge out Phil's eyeballs with his own thumbs.

"Ever hear of snipe fever?"

"No."

"I think maybe I have," admitted Ralph.

"Well," said Phil, "the way you pick up snipe fever is if you fall into a muddy channel, like the one we just crossed. But it has to be the late spring—which it is now, actually—in frog egg‑laying territory, which I suppose would be Frog Island. Anyway, you still have to get some water in your mouth. Well, just a little. Just a drop barely touching your lips actually." Phil locked eyes with Henry. "Because they're microscopic."

"They're real small," Ralph explained.

"Fuck you."

"Exactly," said Phil.

"And so?"

"So most of the time, no big deal. You make it to camp, towel off, and the next day you don't even remember it happened. Most of the time," emphasized Phil. "But if you do get some water in your mouth, even the ittiest, bittiest droplet, and then you find yourself starting to smell kind of...funny. Well, you should probably get to a doctor immediately."

"Why?"

"Of course, there are no doctors on Frog Island. And anyway, we're lost."

"Why, you gimpy four‑eyed Boy Scout rat‑fucker?"

"Because with snipe fever, these microscopic worms—the snipe, which normally feed off the frog eggs, particularly the northern leopard frog, which we got tons of here on Frog Island—they travel down your stomach and start nibbling on your intestines and then they come out the other end, all fat and juicy and still wiggling...”

“Eeeuuuw!” Ralph shrieked like a little girl.

“And brother,” finished Phil, “is it ever painful!"

"Ah, he's putting you on, man. There’s no such thing as snipe fever."

"You just said there was.”

"What do I know, man?"

“You don’t itch, do you, Henry? 'Cause itching’s the first signal.”

Henry clawed his stomach, scratched at his damp scalp like somebody rubbing out head lice.

“Look!” cried Ralph. “He’s got ‘em!”

“No, I mean the other end. No offense, Henry, but does your butt kinda itch? Because if it does, that means you got snipe. You got them bad. Bad! And the only thing to do is to get up there and root ‘em out. Every one of them.”

Henry ripped open his blue jeans at the fly, peeled them down to his knees. He slipped one leg behind the other and curtsied into a crouch, his rear end gingerly thrust forward, his hand slipping into the back of his shorts. As his index finger prodded and drilled, his face made a lemon-eating expression and his hips swayed right to left in a series of jagged thrusts as though he were attempting to corkscrew himself into the dirt. I stared, my eyes popping like flashbulbs. The mighty Henry Eagle.

“What’re you looking at, you freak?”

I closed my mouth but kept gawking. It suddenly occurred to me that Phil was a genius.

"Or even worse, Henry, they go straight to your brain. And they start chewing away at the grey matter. And that makes you so dumb that it takes you five or six years to graduate from high school, and you'll believe anything anybody tells you, even about getting sick from microscopic animals that don't even exist, as any moron ought to—"

Henry stumbled over his jeans as he lurched and flew at Phil's throat. "You little maggot!” he cried, tumbling into the ragweed. “There's no such thing as snipe fever. You were putting me on."

"Tenderfoot initiation," Phil explained warmly. "You don't know nothing about the woods."

"I'm going to pull out your front teeth with my own hands and stab them into your forehead."

"Son," said Mr. Barnes, "I've heard just about enough of those kind of promises."

"Man, he had you going," laughed Ralph, "you really believed him." Ralph mocked Henry with childish exuberance. "Snipe fever!"

"Shut up! I'm going to tear off your arm," Henry told Phil as he yanked his pants back up, "and use it to pry open your rib cage so I can eat your heart raw while it's still pumping."

"Congratulations, son," said Mr. Barnes. "You're now an official member of Troop 623. The only question now is whether you join the Moose or the Indian Patrols?"

For the next two hours, we marched in silence—except for Mr. Barnes, who spoke at length about how we could survive for days if we had to on wild strawberries and the raw meat of salamanders. Being lost had for him grown into an achievement, reminiscent of his entirely imaginary adventures behind the lines with Tito and the Yugoslav partisans. When the sun grew intolerable—a huge pulsing grapefruit looming unbearably close to our dank and dismal little island—we all stripped off our shirts and tied them to our waists, which cooled us down pretty well until around four o'clock, when the mosquitoes descended, enveloping us all in whining billows of stinging black clouds. Henry swatted his face and shoulders while enumerating all the unpleasant things he would do to the insects sometime in the unspecified future. We pulled our sweaty shirts back on and ploughed ahead.

Maybe ten minutes later, Ralph threw down his pack and collapsed upon a dry hillock at the side of the trail.

"Time for a motherfucking break."

We joined him, flattening down a patch of spear grass and sedge. Ralph fished a pack of Camels from his pack, thumped the bottom until an unfiltered end peeked out, and inserted the cigarette into the corner of his mouth. "Who wants a smoke?"

"Son, put those away this minute!"

"Boy Scouts?"

Phil and I declined.

"Hey, c'mon! Sure, you do!" Henry thumped two cigarettes from the pack. "It's time you Boy Scouts earned your Smoking merit badge." He cackled cretinously and dipped into his pack for a can of lighter fluid, which he spurted generously across Phil's trousers. An acrid ping lodged at the ceiling of my throat. When Henry struck the match a waft of sulfur slipped up my nose, and when he tossed it at Phil—and missed—I watched the flame latch on to several stalks of tall grass, explode amid a thick, dry patch like an incendiary bomb, and sprint across the field.

Phil and I popped onto our feet and furiously kicked dirt into the fire. Mr. Barnes stomped an ineffectual tarantella in the middle of the flames. Henry and Ralph rolled in circles, whooping and crowing. “Boy Scouts!” hollered Henry. “Boy Scouts!” The fire rushed up the hill and widened at either side. Phil poured his canteen onto the blaze. I did the same. Henry emptied his can of lighter fluid and watched the flames dance across the tall grass to erect an impregnable wall barring the trail.

“Run!” cried Ralph.

We tore off in the opposite direction, abandoning our packs and our equipment.

Phil took the lead, his legs pumping like mad. I paced directly behind him, my eyes fastened to his heels. I could hear Henry and Ralph wheezing behind us.

Smokers.

Mr. Barnes hollered, “Slow down!”

All I saw were Phil’s two feet switching in front of me. He puddled through swamp, scrambled into bogs, sloshed his way over a crisscross of squelchy trails and parched thicket. The air congealed, growing murky with smoke and the sickly scent of burning sweet grass and charcoal. Henry yelled for us to slow down. Phil sped up. I stopped for a moment to gag and rasp. My lungs felt like shredded cheese. Mr. Barnes hollered at Phil to slow down. He sped up. I followed at his heels, struggling to stick with Phil as he kicked like an Olympian into his last lap, my eyes glued now to his back as it receded in the distance, as my brave and brilliant friend disappeared into a throng of bulrushes.

I tripped and fell over a cross-hatch snare of lasso roots and traveling vines. For a moment, I was perfectly alone, no sign of Phil in front or the others in back. All that mattered was the percussive thump of my own heart nailing itself into the mud. I rose into a crouch and wiped the sweat from my eyes. I knew exactly where I was.

I jogged out of the high grass and tottered into the parking lot, panting and coughing and gulping down all the available air. Other members of the lost patrol soon burrowed out from the greenery behind me—everybody folded over at the waist and gasping, pointing at everybody else, howling who's to blame. An orange glow scored the horizon. The rest of Troop 623 was heaving their backpacks and sleeping bags into the trunks of Mr. Ortiz’s Oldsmobile and Mr. Heilborn’s Buick.

I took my place at Phil’s side and waited for whatever was coming next. Mr. Ortiz was shaking him by both shoulders, demanding an explanation. Phil lowered his head and confessed in a near-whisper that he just wanted to make new guys bitch and moan and blister their feet. He had always known where we were heading. In the distance, tule grass spouted grey clouds like smokestacks.

“Tenderfoot initiation,” he explained. Then he bent over, gagged, and splattered the blacktop with vomit.

“I want to know who set the goddamn island on fire!”

My legs wobbled. I felt scared that I might start laughing. I pictured Henry squatting over the field of ragweed.

"They’re bullies," I peeped up staunchly. “They deserved it.” I patted Phil’s back, and he convulsed once more.

"Barnes!" shouted Mr. Ortiz. “What the hell happened out there?”

Mr. Barnes roused himself from the rear bumper of his Rambler, where he sat crumpled, exhausted, struggling for air. "Those two,” he huffed. “They’ll never get beyond Tenderfoot. They don't take scouting seriously!"

"Not us,” Phil explained, still humped over and rasping. “The other two."

Mr. Ortiz slammed shut his Oldsmobile’s trunk and glared over one shoulder at our scoutmaster. It is extraordinary how much exasperation and dislike can be conveyed with a single shake of the head.

Mr. Barnes scanned the parking lot. He found all of Troop 623 now inspecting his blackened elbows, the grime scuffed into the knees of his trousers. His shirt was torn at the shoulder stitches, his hands and face were filthy. He started to speak, but reconsidered. He daubed one cheek with a grubby palm, applying a faint pancake of charcoal.

“Tell them, Dad.”

Mr. Barnes switched around to face Phil, raised one hand to his shoulder, and then he hit him across the mouth with the back of his hand. Phil spit up blood in a burp of astonishment, tattooing the pavement. Mr. Barnes had everybody's attention now. Even Henry and Ralph's. Certainly Mr. Ortiz, which I suppose was the point. But our scoutmaster just stared at his shoes with nothing else to declare. The soot on his chin gave the rest of his complexion a sickly pallor.

The smoke and ash billowed back into our faces. The air stung from cinders. Fire engines squealed a path in our direction pealing their alarm, and Phil was wailing so loud in his hurt and fury that I could barely hear the approaching roar of flames as the world of our fathers and their fathers before them receded further and further from our comprehension and grasp.

Art Information

- “Family Photo” © Fred Setterberg; used by permission

- From “Boy Scouts Photo Album—Late 1910′s to early 1920′s” © Scarlatti2004; Creative Commons license. (Photographer’s Note: “I found a very old photo album of my Grandfather’s. He was a Boy Scout leader of Troop 2 in South Ozone Park, NY…. These photographs were glued to black paper, which has deteriorated over the decades.”)

- “Theodore Roosevelt in 1885″ by George Grantham Bain; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division; public domain

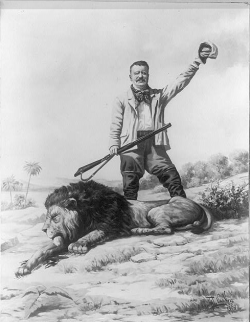

- “Theodore Roosevelt with Dead Lion,” photograph of a drawing by Frank Lewis Van Ness, 1909; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division; public domain

- “Theodore Roosevelt, Kermit Roosevelt, and the Naturalists,” circa 1914; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division; public domain

- “Boys Scouts, Camp Roosevelt,” July 9, 1925 (tents); Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division; public domain

- “Boys Scouts, Camp Roosevelt,” July 9, 1925 (mess hall) by George Grantham Bain; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division; public domain

- “Landscape in the Carmel, California, Area” by Arnold Genthe, circa 1906; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division; public domain

- “”Seeing Things at Night,” by J.S. Pughe, 1905; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division; public domain (Note by LOC: “Illustration shows President Theodore Roosevelt wearing buckskin and raccoon hat, sitting by a campfire at night…; in the shadows beyond the light of the fire are a snake labeled ‘Mormonism,’ a bull labeled ‘Beef Trust,’ [and] a strange bird labeled ‘Merger Bird.’”)

- “The Hunters’ Supper” by Frederic Remington, 1909; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division; public domain

- “Brush Fire” © Sergey Yakovenko; stock photo

Fred Setterberg is the author of Lunch Bucket Paradise: A True-Life Novel, published by Heyday (2011) and The Roads Taken: Travels Through America’s Literary Landscapes (Interlink, 1995), which won the AWP Prize in Creative Nonfiction.

Fred Setterberg is the author of Lunch Bucket Paradise: A True-Life Novel, published by Heyday (2011) and The Roads Taken: Travels Through America’s Literary Landscapes (Interlink, 1995), which won the AWP Prize in Creative Nonfiction.

To learn more, visit Fred Setterberg’s website.

“Escape from Frog Island” is Chapter 5 of Lunch Bucket Paradise. It is reprinted here courtesy of Heyday.