Theme Essay by Mali Sastri

A Songwriter Embraces Her Private Violence

A few years ago, I found myself with a serious writer’s block.

Since 2004, I’ve fronted and managed the band Jaggery. Our sound is difficult to describe, but we try with phrases like "darkwave jazz," "ethereal avant-rock," and "chamber art pop."

Since 2004, I’ve fronted and managed the band Jaggery. Our sound is difficult to describe, but we try with phrases like "darkwave jazz," "ethereal avant-rock," and "chamber art pop."

I love the band, but managing it comes at a price. The semi-instant gratification of booking shows, planning tours, and promoting becomes the main concern, and the reflective, patient, inspired place I need to be in order to write is often, sadly, given lowest priority.

I’m not talking about writing music—that comes easily or, at least, more naturally. It’s the lyrics that trip me up every time. I feel as though the last drop is being wrung from my soul by the effort to find words that not only fit the music but express what both I and the song need to say.

By 2007, I’d slipped into a rut of minimal output. Yet, I found inspiration in a completely unexpected place: a book about a murder.

Five years ago, one of my bandmates lent me In Cold Blood, Truman Capote’s 1966 classic. I'd never heard of it. The book’s subtitle, “A True Account of a Multiple Murder and Its Consequences,” held no particular connotations for me. I had never been a true crime follower and spent little time thinking seriously about violence or murder, mercy or capital punishment.

In Cold Blood profoundly changed all that. Capote's prose—at once descriptive and elegant—drew me into the harrowing tragedy of the Clutter murders, making it hard to put down the book. When I finished it, I realized that my experience with it had gone deeper, beyond mere curiosity. I'd felt an intense connection with the book's most complex character: murderer Perry Smith.

In Cold Blood profoundly changed all that. Capote's prose—at once descriptive and elegant—drew me into the harrowing tragedy of the Clutter murders, making it hard to put down the book. When I finished it, I realized that my experience with it had gone deeper, beyond mere curiosity. I'd felt an intense connection with the book's most complex character: murderer Perry Smith.

In Cold Blood recounts the killing of a wheat farmer, Herbert Clutter, and his wife and two children, which took place in a small farming community in Kansas in 1959—a time when country folk still left their doors unlocked at night.

Capote spent six years researching what he initially planned as a magazine article. He became immersed in the lives of those associated with the Clutter murders, developing a particular closeness with killers Richard Hickock and Perry Smith. The two ex-convicts committed the crime in order to leave no witnesses to a haphazard burglary attempt. After their capture, Capote befriended the men, remaining in close contact with them over the years they spent on Death Row and attending their 1965 executions.

Much has been written about Capote's creation of the hybrid form he called a "nonfiction novel" and how the book permanently altered his work and his life. But none of this interested me as much as his depiction of Smith's complicated psyche, as shown in passages like this:

His own face enthralled him. Each angle of it induced a different impression. It was a changeling's face, and mirror-guided experiments had taught him how to ring the changes, how to look now ominous, now impish, now soulful; a tilt of the head, a twist of the lips, and the corrupt gypsy became the gentle romantic.

Despite Smith's and my drastic external differences—he was an abused, neglected, uneducated young man who had lived a life of poverty and crime, and I grew up in the suburbs with a financially stable and supportive family—I saw myself in him to an astonishing degree. Capote's portrayal moved me, and Perry Smith became something of an obsession.

Despite Smith's and my drastic external differences—he was an abused, neglected, uneducated young man who had lived a life of poverty and crime, and I grew up in the suburbs with a financially stable and supportive family—I saw myself in him to an astonishing degree. Capote's portrayal moved me, and Perry Smith became something of an obsession.I began looking for more information about the Clutter murders, Truman Capote, and, most of all, Perry. I spent countless hours at the New York Public Library, poring over the microfilmed Capote archives.

In 2009, I even traveled to Kansas, fifty years after the murders, on a pilgrimage to visit the Clutter house, Finney County Court House, and many other locations that appear in the book.

I was wary of my fascination with this very dark subject matter. But I was also familiar with Jung's concept of the Shadow—that part of ourselves that's both personally and culturally loathed, rejected, disowned, and unlit. I knew my desire to learn everything I could about a man who had committed an atrocious murder was disturbing. Yet, it was too powerful to ignore, and I chose to follow the dark muse—to trust it and to run with it.

And then the songs came.

It seemed to decide itself. Yes, of course, I would write songs about this.

My music up to that point already had an emphatically dark feel. I’m most moved to write in somber moments, when songwriting becomes a catharsis, a way to create an artistic container around a painful or upsetting situation and thus to transform it.

Much of my lyric writing is fragmentary. I collect bits and pieces of sentences, phrases, word nuggets, that come by their own volition or that I see or hear in the outside world. Perry Smith’s story provided many artistic jumping-off places, both in the events of his life and in the unlikely symmetries I felt between us.

Perry's journey, both as told by Capote and as I found in my research, was bleak and harrowing. It’s also rich with the stuff of poetry and tragic drama. It’s the story of a young man, a sensitive dreamer who longed to be an artist, a musician, and a scholar. Instead, through a life of poverty and abuse, he turned to petty crime and, ultimately, murder.

In Cold Blood paints Perry sympathetically, highlighting his sensitivity, his bleak childhood, his hesitancy to go through with the crime, and the bizarre instances of kindness he offered his victims—on the night of the murders, for example, he prevented Hickock from raping 16-year-old Nancy Clutter.

At one point early in the book, a close friend of Perry tells him:

You are a man of extreme passion, a hungry man not quite sure where his appetite lies, a deeply frustrated man striving to project his individuality against a backdrop of rigid conformity. You exist in a half-world suspended between two superstructures, one self-expression and the other self-destruction.

Lines such as this mirror so many of my own thoughts and feelings—particularly the painful and shameful ones—that it’s as though I’m being led into a secret chamber inside another human being. There I see, not only reflected but clarified and articulated in ways I hadn’t imagined possible, the inside of myself.

If circumstances were different—if my upbringing had been more like Perry's—would I have made similar choices? How is it that destructive impulses can manifest themselves in so many ways, with some people becoming violent toward others, some taking things out on themselves, and some able to channel their impulses into something positive?

What might I be capable of?

In 2008, these questions propelled me to write “Hostage Heart,” the first in what became a series of songs inspired by Perry and In Cold Blood. It includes these lines:

I have wondered what my hands could do

And I have wondered what they are capable of

I have wondered what your hands could do

And I have wondered what they were capable of

Acts of murder and works of art

And if a hostage heart was capable of

Love

The next four songs came in relatively quick succession. In one, "Oh my god," the gritty, grimy jazz arrangement reflects the mood of Quincy Jones's soundtrack for the 1967 movie version of In Cold Blood. The last four lines are a translation of François Villon’s "Ballade des Pendus" (“Ballad of the Hanged”), which opens Truman Capote's book.

By 2010, the band and I had decided to pull together the five songs into the EP Private Violence, released in November 2012. However, I know I haven't yet said or sung all I can about Perry Smith. In an interview with George Plimpton shortly after In Cold Blood was published, Capote expressed the longing and lack of resolution I still feel:

By 2010, the band and I had decided to pull together the five songs into the EP Private Violence, released in November 2012. However, I know I haven't yet said or sung all I can about Perry Smith. In an interview with George Plimpton shortly after In Cold Blood was published, Capote expressed the longing and lack of resolution I still feel:

I’m still very much haunted by the whole thing. I have finished the book, but in a sense, I haven’t finished it: it keeps churning around in my head. It particularizes itself now and then, but not in the sense that it brings about a total conclusion. It’s like the echo of E. M. Forster’s Malabar Caves, the echo that’s meaningless and yet it’s there: one keeps hearing it all the time.

Oh my god

He takes thirteen steps

He’s got seventeen minutes left

It’s called a quick and painless death

This breaking of the neck

Oh my god what have we done?

The hood is placed

To hide the face

So that we can’t see

The look in the eye of the life erased

Oh my god

What have we done?

I do not take the lord’s name in vain

May he have mercy upon your soul upon your pain

The conceit, the arrogance

And the hate, the contempt

And the rage, the revenge

On this world, his only defense

Oh my god

What has he done?

So an eye for an eye

And a tooth for a tooth

Within your song, your dark, dark song

You were harboring your truth

Oh my god

What have you done?

I do not take the lord’s name in vain

The lord he giveth and the lord he taketh away

Witness welcome to the brouhaha

Brother men, who after us live on

Harden not your hearts against us

For if you have some pity on us poor men

The sooner god will show you mercy

Click above to see Jaggery perform "End Song" from Private Violence.

Publishing Information

- In Cold Blood by Truman Capote (Random House, 1966).

- Capote: A Biography by Gerald Clarke (Simon and Schuster, 1988).

- Truman Capote Conversations by M. Thomas Inge (University Press of Mississippi, 1987).

- “The Story Behind a Nonfiction Novel” by George Plimpton, New York Times Book Review, January 6, 1966.

- "In Cold Blood, a Legacy, in Photos," Lawrence Journal World, April 5, 2005.

- "End Song" video by Milk Zombie Productions/Jasmine Inglesmith; used by permission.

Art Information

- Jaggery photo © Noah Blumenson-Cook; used by permission

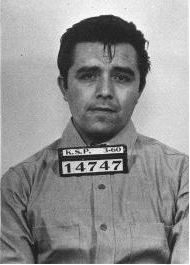

- Kansas State Penitentiary mug shot of Perry Smith;

public domain - "Chinese Elms on the Road Leading to the Clutter House" © Mali Sastri; used by permission

Mali Sastri is the singer, songwriter, and pianist of the Boston band Jaggery. She trained in the expressive arts discipline Voice Movement Therapy (VMT) in London, England. Her singing and songwriting range reflects this therapeutically expressive approach to music.

Mali Sastri is the singer, songwriter, and pianist of the Boston band Jaggery. She trained in the expressive arts discipline Voice Movement Therapy (VMT) in London, England. Her singing and songwriting range reflects this therapeutically expressive approach to music.Mali produces, curates, and performs in the ongoing performance series Org, which plays in various underground-and-otherwise venues in the Boston area. She is a resident of the South End artists co-op Cloud Club and maintains a private VMT practice in Somerville, Massachusetts.

Listen to and download Private Violence and other recordings at Jaggery Bandcamp.