Essay by Joan Frank

Success as a Literary Writer Is…Complicated

My dear friend gaped at me across the dinner table, her earnest gray eyes wide with admiration and love.

“You’ve made it,” she breathed.

This woman is like a sister to me. I’ve known her umpteen years. I love and admire her. She’s a brilliant research scientist—wise, empathic—and has raised three superb kids. She is loyal and faithful.

She knows little about literary publishing.

We were talking at dinner about the fact that I’m bringing out three books this year via three small publishers.

Here’s a bit more background—and foreground: I’ve been writing for thirty years. I have a body of work (including these latest) of ten books. Also, I have no money. I live on Social Security. My retired husband’s pension pays our bills. Any book-related travel, lodging, copies of books for consignment or groups—even snacks and drinks at readings—must be purchased by me.

It’s simply the way things go.

2020 is special and for a happy reason, not just because of the pandemic. Three new books of mine enter the world. I am proud of them. It took years to find them homes. I’d entered two of them in the same contests for several years running until, to my amazement, they won. For the third of those three, it took fifteen years to locate an enthusiastic publisher.

That’s not a typo. Fifteen.

So, when another dear friend, an English teacher, also empathic and bright, suggested I had “finally got what you wanted,” I looked at her with the same blank incredulity my face assumed when my scientist friend breathed, “You’ve made it.”

“No,” I said to each woman slowly, carefully, my face wide with a near-pitying compassion.

No, I did not get what I wanted.

Both looked at me, uncomprehending. What then, asked Friend Number Two, did “getting what you wanted” look like?

My answer popped forth as if memorized, which it pretty much is: “A contract with a major house. A modest advance.”

Sadly, that answer, in our present moment, engages a whopping level of fantasy.

• • •

Once, long ago, in a state of innocence encouraged by eager articles in writers’ magazines, I was convinced I would eventually find an agent who loved and believed in my work—enough to sell it, for actual money, to a large, respected, literary publisher.

With publication—naturally—would come good critical recognition. With that would come another contract/sale. In this way, I reasoned, my artistic trajectory would unfurl.

Such dreams are now remnants—like historic fabric swatches—of a bygone era: say, that of Katherine Anne Porter, whom I imagine placing a story in her mailbox, going indoors to paint her nails, and returning to the mailbox a few days later to obtain her check.

Those dreams may still play out for some, but for literary writers, such remnants of a kinder time are almost insanely rare. Grasping this reality happened for me the way Hemingway described going broke: slowly at first, then very, very fast.

So, I have no agent. I gave up that search after many years. Hundreds of agents praised-but-declined the offered work (“too literary”). I entered contests instead and eventually won five. All my publishers are small, literary, or university presses. They’ve been conscientious, legitimate—meaning not author-funded—and yes, very small. I quietly explain, to anyone who asks, that this situation summarizes my lot and my oeuvre.

I’m truly thankful my books exist in the world. I’m thankful for those literary contest victories, which allowed me to build an oeuvre at all.

But “making it” is not how I’d describe what has happened.

When I see authors today receiving big splashes of publicity in major media or agents selling new works to major houses for stunningly large sums, I try to muster some mental and emotional distance. Even so, the unasked how? murmurs uneasily inside me, as I think it does for most writers. Sometimes it’s luck. Sometimes someone knew someone. Each splash represents a huge bet on the part of the publisher, as with racehorses. Sometimes the bet triumphs. Often, not so much.

Now: If you’ve already dwelt in this game for some while, you’ll recognize all the above. And you’ll know there’s only one cul de sac where these thoughts must end up. It’s a constant re-reckoning: an existential dusting of hands, a hitching up of one’s pants. Emphasis on constant.

• • •

First, consider the modest advance. Why seek money? Not only does literary writing bring little or no money; it actually costs a writer (see above note about buying your own book copies, snacks, drinks). Partly, I ask for money because I want to be accorded a basic dignity: This is my warranted profession and its real product, my booth in the marketplace.

But more deeply, writers like me seek money for another reason. Richard Bausch is eloquent in one passionate “Reprise,” occasional writerly advice he distributes on Facebook (italics are mine):

One of the most endearing things about all the writers I know...is that...[t]hey want money of course...but when they get it they use it mostly to buy one thing: Time. That’s all any of them want. To be able to purchase a little Time from the world’s daily demands, and they want that time, all of them that I know, for one reason. To work.

What’s more, fame and notoriety, even the most flamboyant, can prove fleeting. In his 2019 Poets & Writers article “Author Envy: The Art of Surviving One’s Own Personality,” William Giraldi notes (italics mine):

Some of those writers with all the laurels and grants and sales today will likely not be remembered in thirty years, never mind in three hundred, so you have to put it to yourself: What’s your intention with literature? What do you want from it? Are you an artist because you cannot be otherwise…or because you want cheers from strangers and plaudits from the lit establishment?

To deflect a knee-jerk wisecrack: Yes, most of us, despite the screamingly consistent realities, want both: the soul-feeding part and the cheers-and-plaudits part. Few cop to that. And sure as eggs, we get disabused of this secret longing around the clock. Giraldi suggests we’d do better to aim our disgruntlement at those who seek to thwart writers and art in general. That’s noble. But it’s a red herring. The irreducible Why do you do this? forces me to focus. It draws the predicament’s true, eternal bottom line.

“It is not your fault, it is not my fault, that I write,” James Baldwin told an audience at a New York City church in 1962. “And I never would come before you in the position of a complainant for doing something that I must do.” This talk was also broadcast on the radio as “The Artist’s Struggle for Integrity” and appears in Baldwin's posthumous collection The Cross of Redemption.

Something that I must do. No more nor less. No one holds a gun to our heads. No writing police (this image, famously, from Anne Lamott) bash down the door at 4 a.m. demanding new work. The whole gambit’s still an act of free will against tragicomic odds. And our energies and well-being, as we keep doing it, are never promised protection at any level.

Why is it, I keep wondering, that we must re-identify and re-absorb the above hard truths at every turn? Because hysterical culture drowns them out. It’s hard to think clearly while the volume’s turned up. I confess it feels more difficult than ever to turn back to the work—to let all the noise, dust, and confetti flutter past.

Yet that’s the task: to understand it’s your choice. Nothing else is given. Rump parked in chair, hands poised over paper or keyboard: the only sanctuary, the only solace, the only control; the place where one feels purposeful, defined, alive. Don Lee’s 2018 piece in Electric Literature, “What’s the Point of Writing If You’re Not Going to Succeed?,” is the baldest-truth-yet account of the dilemma. Lee says of the late Richard Yates, a writer who suffered hellishly:

It was what he did. It was who he was. He kept writing, even when there were so few rewards to do so, even when the work was hard, and lonely, and unfulfilling. It was his life. It was his calling.

All the reading. Piles and piles of heavenly books—each of which I take up at day’s end like a hymnal and, once sung through, I murmur or think, thank you.

Making good work, and reading others’ beautiful works, are certainly what I’ve wanted—never stopped wanting. And I have made sure, somehow, that I always did get them.

But in addition?

I’m human. I contradict myself. I contain multitudes. I will probably always feel badly, sad, even bewildered about not “making it.” And I will bet a huge portion of anything you’ve got (beer, marbles, candy) that no matter how well they behave or how “successful” we may assume them to be, bazillions of writers in their secret hearts feel exactly the same.

The simultaneous, not-so-secret-secret is that there is no choice.

Except there’s always a choice, and we to have to re-choose and re-choose repeatedly, constantly—like being shot to death every minute of your life.

Publishing Information

- This “Reprise” and others by Richard Bausch appear in his Facebook postings; he’s given the author and TW permission to quote from one here.

- “Author Envy: The Art of Surviving One’s Own Personality” by William Giraldi, Poets & Writers, May/June 2019.

- “The Artist’s Struggle for Integrity” in The Cross of Redemption: Uncollected Writings by James Baldwin, edited by Randall Kenan (Random House/Vintage, 2010).

- “What’s the Point of Writing If You’re Not Going to Succeed?” by Don Lee, Electric Literature, July 30, 2018.

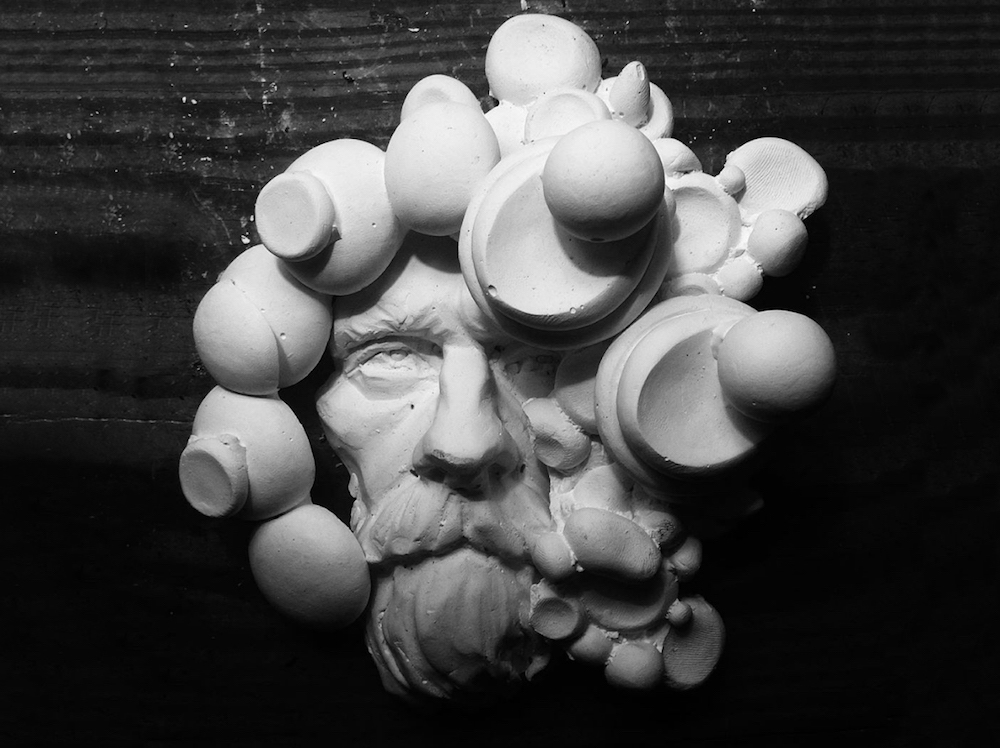

Art Information

- “Prototype,” “Camouflage Prototype” and “Prototype 3” © Troy Wandzel; used by permission.

Joan Frank is the author of ten books of literary fiction and nonfiction. Where You’re All Going: Four Novellas won the Mary McCarthy Prize for Short Fiction. Try to Get Lost: Essays on Travel and Place won River Teeth’s Literary Nonfiction Book Prize. In October 2020, her new novel, The Outlook for Earthlings, will be published by Regal House Publishing. For her book of essays, Because You Have to: A Writing Life, Joan was named Foreword Magazine’s Foreword Indies Silver Winner for Writing.