TW Column by Judith A. Ross

Seeking the Real Person in the Online Persona

David Terry calls himself an illustrator, a craftsman, a copyist—anything but an artist. According to his website, he doesn’t like hobnobbing with art critics, pretentious artists’ statements, or any of the other “hoops & jumps” that he considers “transparently self-serving”:

"Quite frankly? I can sit at home with most of my friends, look at my pictures while we drink boxed-white-wine from the Food Lion, and none of us needs to even put on shoes.

That sounds fun to me, too, and I wish I could join them. Yet, an online persona is still a persona. I might not fit in as easily as I’d like to think.

That sounds fun to me, too, and I wish I could join them. Yet, an online persona is still a persona. I might not fit in as easily as I’d like to think.

Terry may have good reason to dislike formal artists’ statements in galleries. But these days, a freelance professional’s website and Facebook profile are also statements.

He’s a TW featured artist—and, yes, we say artist—because I first met him online, visited his website, and liked the artwork I saw. He and I are frequent commenters on Dominique Browning’s blog Slow Love Life. His responses to her posts caught my eye more than a year ago, especially when he addressed my comments. Terry has advised me on my puppy’s chewing habit, prescribed a hand cream for my husband, even suggested architecture books for our last trip to Europe.

Thus began my odyssey (a literary allusion I think he’d appreciate) to figure out if the online David Terry I know matches the actual person in his studio. I have yet to encounter him or his work in “real” life. I’m still pondering what distinguishes art viewed online from the stuff hanging on walls.

I did interview Terry by phone this past October and December. His answers to my questions were punctuated by a smoker’s laugh. A longtime resident of Durham, North Carolina, he spoke with a barely noticeable Southern inflection, often lilting his voice upward at the end of a statement. He frequently meandered into elaborate tangents.

Do I know him any better now? Probably not. But talking to him was every bit as entertaining as reading his online comments.

Terry is hard to pin down partly because his prolific body of work crosses all sorts of stylistic boundaries. He creates landscapes, portraits, montages, book covers, and posters. He sums up his approach by telling the following story, which includes his “favorite comment” from a critic.

Terry is hard to pin down partly because his prolific body of work crosses all sorts of stylistic boundaries. He creates landscapes, portraits, montages, book covers, and posters. He sums up his approach by telling the following story, which includes his “favorite comment” from a critic.

In 2000, at Terry’s one-man show in Durham, a local newspaper columnist perused the offerings: a mix of straightforward images of dogs and horses, and, in the artist’s colorful terms, “these wacky, campy, multi-image satiric things.”

“This is the best two-man show I’ve ever seen by one person,” the critic later told Terry.

“It’s just the two different sides of me,” he adds a decade later. “I love them both. I don’t see a need to differentiate.”

Terry, who recently turned 50, grew up in the small town of Greeneville, Tennessee. He laughs about his “very Southern, preppy family” who had to put up with his first creations. A ’70s kid, he had a loom and all the Foxfire books about Appalachian folk culture.

His mother would be showered with Christmas gifts like macramé vests, he notes, or there would be “a four-inch-wide white woven belt for my father, a 30-year IBM executive who spent all of his days wearing a white shirt and dark-blue suit.”

Terry says he never took a formal art class beyond grade school. “In college, I drew pictures for the frat newspaper. Never thought about it,” he adds. “At first I wanted to be a lawyer. I thought that meant having a big mahogany desk, and a long-legged secretary who quietly passed you coffee.”

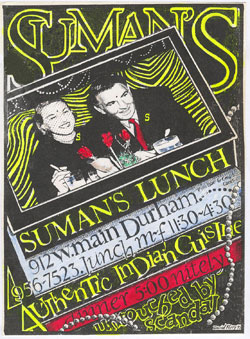

But he was unable to keep his creative side completely submerged, and, by his account, it broke free in the oddest way. In 1990, when he was writing a dissertation about Thomas Hardy at Duke University, Terry befriended Suman, the owner of a local Indian restaurant.

Suman was shocked by the amount another artist charged her for advertising. “Anyone can draw,” Terry recalls telling her, and with that, he took over creating the restaurant’s ads, which appeared weekly in the local alternative newspaper.

Suman was shocked by the amount another artist charged her for advertising. “Anyone can draw,” Terry recalls telling her, and with that, he took over creating the restaurant’s ads, which appeared weekly in the local alternative newspaper.

”It was a complete relief for me,” he says. “I was studying under every rigid ideologue you could find in the English department, so I reacted by doing the most blatantly politically incorrect ads I could.”

In 1993, Terry had another epiphany while at the yearly Modern Language Association conference. He describes standing at the top of a staircase watching thousands of academics milling around below.

“It’s like a huge anthill down there,” he remembers thinking. “I don’t want to be one of these people.”

Given the success of his Suman’s ads, he soon had more work, doing newspaper illustrations, book covers, and even a cookie box for Whole Foods. By the late ‘90s, he’d become a full-time illustrator, freelancing for the book section of the Washington Post and for Green Linnet records.

Doing noncommercial work that might hang in a gallery didn’t occur to Terry until 1996, when he was asked by Durham gallery owner John Bloedorn if he’d ever thought about giving a show. That same year, Terry created 33 pieces for Bloedorn’s Craven Allen Gallery. He’s been with Bloedorn ever since. Galleries in Charleston, South Carolina; Barboursville, Virginia; and several cities in France also represent his work.

Terry told me he’s lived in the same Durham house for eight years. While he does have a designated studio with bookshelves and a drawing table, he generally works on the kitchen floor “wearing shorts and a tank top.”

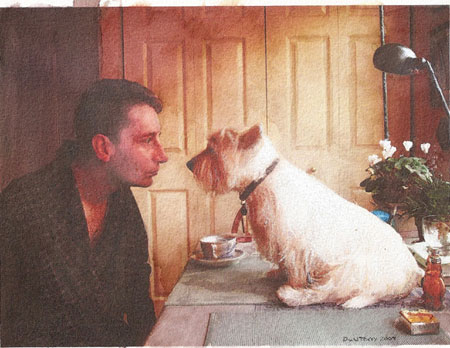

I don’t know what Terry looks like beyond the picture on his Facebook page and the one that appears with this column. I’m used to visiting physical workspaces. I love talking to visual artists face to face, matching what they say with the creations surrounding them in their studios. Here, though, I’ve had to match the artist’s voice on the phone with the words and images I see online.

I don’t know what Terry looks like beyond the picture on his Facebook page and the one that appears with this column. I’m used to visiting physical workspaces. I love talking to visual artists face to face, matching what they say with the creations surrounding them in their studios. Here, though, I’ve had to match the artist’s voice on the phone with the words and images I see online.

He says his portraits usually start with a photograph—if one exists. He traces the outline using a light table and then creates the image by making millions of tiny dots with a rapidograph pen.

The largest piece he’s ever done is 30 inches tall, Terry claims. Based on what I’d seen online, this surprised me. Does he keep the online appearance of an image in mind as he works? “No, not in the least,” he answers without hesitation, though he does consider how it will look when published in a magazine or newspaper.

By keeping things small, Terry points out, he can work “the way a woman might do petit point from one end of the sampler to the other. I love that sort of intensive work.”

Because he is colorblind—another surprise—he only uses a handful of hues, which gives such drawings the feel of old-time book and magazine illustrations. “I don’t see many colors,” he says, “but I do contrasts better than anyone.”

Commissions keep him busy now. Just recently, he says, he was invited to give a show at the American Embassy in Senegal. He travels several times a year to France with his partner Hervé.

Still, he is nonchalant about his success. “I’m not very interested in my own work,” he says. “It’s just a talent I have, the way some people are double-jointed. I can draw very, very accurately. I’m interested in other people’s projects and lives.”

Does that make him something other than an artist? I don’t think so. Art forges connections, causes viewers to think, and presents a point of view.

Although I’ve only observed David Terry’s work on a computer screen, it moves me—and it reminds me that all art is a mediation of reality. So are the stories we tell about our lives, and, in today’s virtual landscape, who’s to say which version is real?

To learn more about this artist, visit David Terry’s website.

Judith A. Ross is contributing writer and columnist at Talking Writing.

Judith A. Ross is contributing writer and columnist at Talking Writing.

Last summer, her then eight-month-old puppy was chewing up a storm, so she was delighted when David Terry weighed in with advice on Slow Love Life:

"[T]he best tip for puppy-raising I've ever had was from my mother.... Amusingly enough, it's a trick she used with her three sons when we began teething. Most folks in the early sixties simply relied on Peregoric; my mother, quite reasonably, wasn't particularly keen on having a bunch of narcotized infants in her house.... [S]he simply gave us frozen carrots. I gather we all gnawed happily on them during the entire teething period. They dull the pain and are good for the baby. I've raised all my puppies (I keep very "chewy" west highland terriers) on frozen carrots." — From "Moving Back in with Mom" by Dominique Browning, Slow Love Life, June 9, 2011