Introduction by Carol Dorf

Traveling in Instantaneous Time

Poetry and fiction address the passage of time in distinctly different modes.

Fiction offers the illusion of characters moving through time, whether over years, as in War and Peace, or in the course of a single day, as in Mrs. Dalloway. In poetry, everything happens in an instant.

Fiction offers the illusion of characters moving through time, whether over years, as in War and Peace, or in the course of a single day, as in Mrs. Dalloway. In poetry, everything happens in an instant.

Consider Harryette Mullen’s “Black Nikes,” which begins:

We need quarters like King Tut needed a boat. A slave could row him to heaven from his crypt in Egypt full of loot. We’ve lived quietly among the stars, knowing money isn’t what matters. We only bring enough to tip the shuttle driver when we hitch a ride aboard a trailblazer of light. This comet could scour the planet.

Mullen’s poem covers “big events”—funeral rituals, a comet plummeting into the earth—yet this isn’t the life and death of fiction, where one event leads to another. Here, the past and future blaze together all at once, from ancient Egypt to the end of time.

To me, intermediate forms like prose poetry—a hybrid of fiction and poetry—concentrate the energy of language to surprise and delight the reader. Many of our most exciting submissions have been in this form. That’s why we’re turned our annual poetry spotlight to prose poetry. Our Jan/Feb 2013 issue will feature prose poems every Wednesday, gathered from nine poets across the United States and beyond.

In the European/American tradition, prose poetry began in the early 1800s, when the French writer Aloysius Bertrand rebelled against the constraints of poetic form. Bertrand’s Gaspard de la Nuit, first published in 1842, a year after his death, is widely recognized as the pioneering work of the genre.

In the European/American tradition, prose poetry began in the early 1800s, when the French writer Aloysius Bertrand rebelled against the constraints of poetic form. Bertrand’s Gaspard de la Nuit, first published in 1842, a year after his death, is widely recognized as the pioneering work of the genre.

In the Japanese tradition, pillow books, beginning with Sei Shōnagon in the early eleventh century, contain much that we would see as prose poetry. Basho’s seventeenth-century haibun are also early examples.

For contemporary poets, the form continues to raise questions about the dividing line between narrative poetry and prose—and, consequently, poses the most difficult challenge to the idea of the relationship of time to poetry. While narrative poetry does refer to events taking place over time, each incident is presented in the intensity of the moment.

The term “prose poetry” itself speaks to the confusion. Why the ungainly juxtaposition of a descriptor before the word poetry? We wouldn’t say “sonnet poetry” or even “free verse poetry.” Both readers and writers tend to feel uncomfortable with intermediate forms.

In the recent Talking Writing piece “Do We Need Prose Poetry?,” which engendered a lively discussion about the distinction between poetry and prose, author David Meishen pointed out a passage of poetic prose in Hemingway and even titled it. I agree that many works of fiction contain passages that rival poetry in linguistic intensity. However, I still see an essential difference in the way the two forms handle the passage of time. In a work of fiction, these poetic pauses focus the reader on the intensity of the moment so they are able to pay attention to detail—the way we do in poetry, when time stands still.

Of course, there are intermediate cases. In The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis, some pieces, like “Losing Memory,” handle time in a way I’d label poetry:

Of course, there are intermediate cases. In The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis, some pieces, like “Losing Memory,” handle time in a way I’d label poetry:

You ask me about Edith Wharton.

Well, the name is very familiar.

Others, like “Letter to a Funeral Parlor,” follow a character’s thoughts and actions through the passage of time.

Some writers, such as the Argentinean Ana María Shua, label their works as micro fictions, even though I’d consider many of these pieces to be poetry. Here’s an example of one of Shua’s “fictions,” #16 from La Sueñera (Dream Catcher).

“In the darkness, a pile of clothes on a chair appears to be a shapeless animal about to devour me. After I turn on the light, I calm down, but now I’m awake, and unfortunately I can’t even read. With that light blue shirt sinking its teeth into my neck, I find it impossible to concentrate.

Now, for me, when we get into the territory of carnivorous shirts, we’re in the world of either science fiction or poetry. “In the darkness,” stays in the terrain of poetry, where the states of being awake and being asleep have equal weight, and the self attempts to make sense of an absurd situation.

Now, for me, when we get into the territory of carnivorous shirts, we’re in the world of either science fiction or poetry. “In the darkness,” stays in the terrain of poetry, where the states of being awake and being asleep have equal weight, and the self attempts to make sense of an absurd situation.

I would say that the primary reason poets write in prose (or fiction writers create moments of prose poetry) is to create a sense of onrushing momentum, of images and events crashing into each other. This strategy plays an important role in structuring a number of the poems in this issue.

Jerry McGuire’s arresting narrative poem “Photographer, Gulf Coast” tells of a cameraman photographing tattoos who ends up with a very different story than the one he expects. Adding to the complexity, “Photographer” contains an embedded folk tale, as well as a long monologue. But the material is presented as a story of rapid shocks, and the frame compresses the embedded stories into the present.

Randall Horton’s poem “After Ruin” includes the lines:

Ruin does this and perhaps is evermore tied to beauty. In the pursuit of beauty there is always already a series of invisible vertical bars, the indented metal shadows streaming across your face, reminders of how you border yourself off, reduced to a subjugated human in a cell…

Here, the language of the essay is interrupted by the language of the poem, disrupting our experience of reading the prose. We end up questioning the idea of beauty and ruin and how this poem itself marks out its staging of idea and image.

In “Outlaw,” Metta Sáma follows a similar strategy, trying to answer a question—one that’s too often suppressed in our dialogs about violence—by writing about the idea of the frontier in the context of American white men’s relationship to guns.

“What is law to such a man? He. Is. law. He who cleared the land to build the road to mark the house to make the man. Is law.

Prose poetry invites contradiction. Readers encounter vital issues like death or war in the same poem where someone is making wine or casually walking into a shop and taking tourist pictures.

Prose poetry invites contradiction. Readers encounter vital issues like death or war in the same poem where someone is making wine or casually walking into a shop and taking tourist pictures.

In the same way, a person whose life has been at risk will often say, “My life passed before my eyes.” What they mean is that a set of images from their life flashed in front of them—a hug from a parent, looking down at a vista, playing with a pet, spooning with a lover. In those flashed instants, there were no transition sentences. Each image served to symbolize a moment.

In “Madrigal,” the Swedish poet, Tomas Tranströmer, writes:

I inherited a dark wood, but today I’m walking in the other wood, the light one. All the living creatures that sing, wriggle, wag, and crawl! It’s spring and the air is very strong. I have graduated from the university of oblivion and am as empty-handed as the shirt on the washing line.

Perhaps the best way to approach the prose poem is with empty hands, ready to hold whatever is offered in the moment.

TW Jan/Feb 2013 Spotlight on Prose Poetry:

- Lois Marie Harrod: “Marlene Mae Thinks Like a Slug”

- Trina Gaynon: “Underground”

- Metta Sáma: “Outlaw”

- rob mclennan: Four from “Notlake utanikki”

- Randall Horton: “After Ruin” and “Sandy: Aesthetic Memory”

- Jerry McGuire: “No Answer” and “Photographer, Gulf Coast”

- Wendy Brown-Báez: “Sake”

- Carol Dorf: “On the Way Out of the Memory Palace”

- Iris Jamahl Dunkle: “Dear Denise Duhamel”

Starting Points for Prose Poetry

- The Prose Poem Project: A Literary Journal Devoted Entirely to the Prose Poem. The Summer/Winter 2012 issue contains work by TW poets Lisa Cihlar and Howie Good.

- The House of Your Dream: An International Collection of Prose Poetry, edited by Robert Alexander and Dennis Maloney (White Pine Press, 2008).

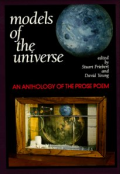

Models of the Universe: An Anthology of the Prose Poem, edited by Stuart Friebart and David Young (Oberlin College Press, 1995).

Models of the Universe: An Anthology of the Prose Poem, edited by Stuart Friebart and David Young (Oberlin College Press, 1995).- Great American Prose Poems From Poe to the Present, edited by David Lehman (Scribner, 2003).

- “The Eye and the Page” (“Visual Cues: Typography’s Potential in the Prose Poem”) by Ann E. Michael, Poemeleon: A Journal of Poetry, Winter 2007. This essay is part of “The Prose Poem Issue.”

- “Mutable Boundaries: On Prose Poetry” by Karen Volkman, Academy of American Poets website.

Publishing Information

- “Black Nikes” by Harryette Mullen, originally published in Santa Monica Review, Fall 1997.

- Selections from Gaspard de la Nuit by Aloysius Bertrand (first published in Paris in 1842 by the poet's friend, sculptor David d'Angers; now available in a variety of versions and languages).

- The Pillow Book of Sei Shōnagon, translated and edited by Ivan Morris (Columbia University Press, 1991).

- “Do We Need Prose Poetry?” by David Meischen, Talking Writing, Nov/Dec 2012.

- Selected work by Lydia Davis from The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2009).

- La Sueñera by Ana María Shua (first published in Argentina by Minotauro, 1984).

- Quick Fix: Sudden Fiction by Ana María Shua, translated by Rhonda Dahl Buchanan and containing portions of La Sueñera, including #16 (White Pine Press, 2008).

- For the Living and the Dead: Poems and a Memoir by Tomas Tranströmer (first published in Sweden by Bonniers, 1989; HarperCollins Publishers, 2011).

Carol Dorf is the poetry editor at Talking Writing. This introduction to the prose poetry spotlight is a special edition of TW's "Talking Poetry" column.

Carol Dorf is the poetry editor at Talking Writing. This introduction to the prose poetry spotlight is a special edition of TW's "Talking Poetry" column.

"Time and space, what more is there to complain about, though a higher intellect would critique rather than settle for this whine. In a just world, you could flip time end over end, until you reached the place where you actually belonged." — "Library Hours"