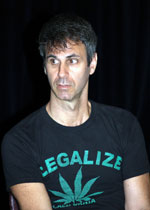

TW Interview by David Cameron

Sex, candy, and rock-and-roll: the obsessions of author Steve Almond. Whether he’s recounting the humiliation of adolescent sexual exploits or exploring the relationship between chocolate and human transgression, his work always has me reckoning with my own baggage.

Sex, candy, and rock-and-roll: the obsessions of author Steve Almond. Whether he’s recounting the humiliation of adolescent sexual exploits or exploring the relationship between chocolate and human transgression, his work always has me reckoning with my own baggage.

For Almond, nothing’s off limits. He writes both fiction and nonfiction, and his essays touch on everything from “my Republican homeys” to a “reluctant exegesis of the song ‘Africa’ by Toto.”

Yet, his hilariously disturbing material is often a back door into human compassion. In the title story of his new collection God Bless America, for instance, an everyman character named Billy Clam relentlessly pursues his ambition to be an actor in a way that’s both inspirational and cringe worthy.

In 2002, Almond roared onto the literary scene with My Life in Heavy Metal, his first book of short stories. Then came Candyfreak, tales of candy production across the U.S. mixed with his own lust for sweet stuff. As he notes at the start, "The author has eaten a piece of candy every single day of his entire life."

I first met Almond this past spring, when I took a workshop with him called “Funny Is the New Deep” at Grub Street in Boston. He made clear that humor is an essential vehicle for exploring our deepest humiliations. Since I’ve amassed quite a few over the years, I then asked him to critique two of my own stories. As a result, I’ve internalized what he describes as the “Hippocratic Oath” for writing: Never confuse the reader.

I first met Almond this past spring, when I took a workshop with him called “Funny Is the New Deep” at Grub Street in Boston. He made clear that humor is an essential vehicle for exploring our deepest humiliations. Since I’ve amassed quite a few over the years, I then asked him to critique two of my own stories. As a result, I’ve internalized what he describes as the “Hippocratic Oath” for writing: Never confuse the reader.

This past Labor Day, I interviewed Almond for TW at his home just north of Boston. It was one of the summer’s last swampy days, rendered more so by a pot of soup simmering in his kitchen. We sat in the living room of his surprisingly well-kept house. (He and his wife Erin Almond—also a writer—have two small children.)

We made quite a pair. Almond had recently injured his back while, of all things, cooking and said he’d dosed himself with Xanax. I'd just returned from the New Hampshire State Fair, where a ride that was supposed to mimic the sensation of hang gliding had left me in a state of flu-like vertigo.

Still, we managed to cover the basics: life, death, writing.

DC: Your house smells of soup right now, and this is the TW food issue, so let’s kick this off with Candyfreak. Food writing, not to mention food TV, has come a long way since your book was published almost a decade ago.

SA: The thing that people responded to in Candyfreak was that it’s about something everyone has in common. Eating is the central experience when you’re a baby; your mouth is the major exploratory organ. We all eat, and we all think about eating much more than we admit. Half the channels on TV are food porn at this point. There’s so much sensual data there to be mined.

DC: Sex writing is also something you’ve gained a bit of a reputation for.

SA: Actually, Candyfreak was a response to sex writing. I’d been writing these very intense dark sexual stories, and I thought that now I should just write something light. But when you go into any subject really deeply, you end up getting into all your stuff—your family, your childhood, your assembled anxieties and sorrows. The book ended up really being about all that dark stuff. Candy is the first great transgression in our lives.

DC: I’ve noticed that your stories tend to be very plot driven. In your writing, stuff happens. Death, high stakes gambling, police drug busts. That’s uncommon in literary fiction.

SA: There are certain writers, such as Don DeLillo, whom I think of as the “great mind school.” The reader’s motive is to spend time with a great mind, to see what a really brilliant person is noticing. That’s not me. I’m not a good enough writer to make a story out of a series of riffs or observations. Charles D’Ambrosio can do that. Even if the anecdotes assembled don’t have a traditional narrative arc, you still feel immersed in a particular character’s life. His stories try to capture modern consciousness.

My ethos is that you should try to break the reader’s heart, to implicate the reader in a very emotional situation. The writer’s job is to take account and pay attention to the sorrow everyone’s lugging around. And for everyone who wants to ignore that, there’s a million cable channels.

DC: There’s a lot of sorrow in those channels, too.

SA: People respond to reality TV because they need a set of people who are pettier than they are, who make worse decisions. This stuff is just evidence of our own pathology. The culture is designed to keep us from paying attention to complicated and unsolvable feelings, the ones Oprah won’t get rid of, everything that’s hiding behind the grievances.

DC: From a purely practical standpoint, it’s pretty hard for anyone, not only writers, to stay in that zone and take notice.

SA: Absolutely. It’s exhausting. It’s hard work to be in a room and recognize the pain and look at it and pay attention to it. Pursuing this sort of thing puts us way out on the edge. And that’s precisely why writers need community. We need it because even though we’re out on the edge, we need to feel like at least we’re in the middle of something.

DC: I’ve noticed that many of your stories culminate in a kind of crescendo of language. There’s a musical aspect to it. How intentional is that?

SA: When you’re really connected to a character and you get them to an emotionally complicated situation, the language intensifies on its own. It becomes more poetic and compressed, because it needs to be in order to capture the full truth of the moment.

Early in their careers, people tend to think that the idea is to get a lot of beautiful language on the page. It’s the lasting temptation we’re drawn to. We love having a voice and showing off and being heard. We want to emulate those who make us jealous.

But what I see in other people’s writing that sometimes makes me feel dispirited about my own work is the level of precision and concentration. It’s partly a matter of the style and the vocabulary at their disposal, partly their imaginative reach, but it’s mostly a sense of them really concentrating and getting deeply inside a particular character and story. There’s no substitute for that. You know when you’re there as a writer, and you know when you’re just pretending to be there.

DC: In God Bless America, I really loved the story “What the Bird Says.” In fact, last night I read it to my wife and three kids.

SA: You didn’t.

DC: I did. The four-year-old crashed, the nine-year-old zoned, but my twelve-year-old stayed with it the whole time.

SA: Wow.

DC: I think it was the flirtation with magical realism that held him. In this story, an estranged son returns home to his dying father, who turns out to have been a deplorable human being. The father experiences a bird on his shoulder whispering to him all sorts of “inside” information about the people around him. At certain moments, I found myself wondering if the bird was real.

SA: Well, I did want there to be that element. The bird is his subconscious to some extent. Everyone can try to run away from their internal lives—or try to run away from the suffering they see in the people around them—but they can’t. This is a story about reckoning. The kid has to go back and reckon with his father and the love that became distorted between them. The dad also is trying to reckon with how he hurt everyone around him, broke the hearts of his daughters, forced his wife to lead a very emotionally curtailed life. He was very self-involved and destructive. But death has a tendency to force the issue. The story takes a risk at being sentimental.

DC: But it packs an emotional punch. In the last paragraph, the language escalates and you, the author, suddenly place the action in a kind of—forgive me for using this word—cosmic context.

SA: Well…I was reading Chekhov at the time. I got to the end of this story and could see very clearly that if you know the characters well enough and if it’s an important moment, it becomes universal. It isn’t just a father and son in a room. It’s earth and heaven.

In any honest story, you try to build an emotional ramp to the moments that matter. Then you slow the fuck down. That’s where Chekhov emboldened me. I said to myself, I’m going to write a big ending here, one that pulls the camera back, and I’m going to show the invisible threads keeping it all together. I’d rather take a big swing and strike out than not swing. Whether it works is the risk you take.

DC: What about the role of research in writing fiction? In this story, there’s tremendous factual National Geographic-scale knowledge about birds and trees. Did you spring from the womb knowing this stuff?

SA: No! Some writers like DeLillo are amazing at this, providing all this detail on what it takes to be, say, a risk analyst for the CIA. This story was inspired by someone I know who is a tree surgeon. I had to do a lot of research, to figure out what kind of trees exist in the area the story occurs, what they looked like. I don’t have that knowledge. Now you, as a writer, don’t want to get too bogged down in the research, but you need to get it right. To overlook such detail is a form of carelessness and inattention, a betrayal of who the character really is.

DC: Let’s talk about Billy Clam, the aspiring actor in the title story of God Bless America.

SA: Billy Clam is an archetypal figure. He’s a little too smart for his circumstances, and he really wants to be somebody. I did just want to have some fun. When I wrote the story, I felt a lot of sympathy for him. I like that Billy Clam goes for it, that something in him is indomitable. Is he really an actor? Who knows. The point is that he believes he is. The story asks the question: Do we live in our circumstances, or do we live in our expectations? The ending can be read either way.

I don’t want the reader to look at him and think, Oh, what a fool. I want the reader to feel the ways in which they too have these exalted, maybe doomed, but still precious hopes. That’s what Billy Clam is enacting.

DC: It’s noteworthy that you’ve chosen to title your book God Bless America, considering that you yourself spent fifteen minutes as a Fox News piñata. I assume there’s a comic impulse behind the title choice.

SA: I called the book God Bless America for a reason. The comedian is a heartbroken idealist. This is the greatest country that has ever existed. America was founded on beautiful ideas. I’m not being unpatriotic by expressing how heartbroken I am that we’ve turned away from the better angels of our nature. I’m desperately trying to figure out how we can turn it around and start caring about each other more. In my writing, I’m not just poking a stick and saying, “Dumb patriots.” I love this country, but I’m heartbroken.

This gets to art and the question of whether people will be awakened to the suffering of others. The only way I know how to deal with the tiresomeness and self-righteousness in my personality is to let the comic impulse make some of those moral points. “God Bless America” as a story has little funny riffs that make a point about how America is the land of opportunists and how it really was founded by vicious, opportunistic people. We haven’t been able to shake that. That story was intended to be a comic story, but like anything that’s really good comedy, it’s trying to point to a fundamental truth.

DC: One of the obligatory questions in author interviews is, "What advice do you have for young writers?" But I’d rather ask you this: What advice do you have for old writers, those of us who have been slogging away for years and whose lives are constricted by myriad adult responsibilities?

SA: Well, this points back to "God Bless America." What Billy Clam is really reaching for is to feel connected to his internal life. The general advice I have for writers is to connect with some part of your life that you’ve allowed to remain dormant, to experience deeply the emotions inside you and the emotions of the people around you. Whether it’s in fictional disguise or memoir or poem, you have to take pleasure in that and not confuse it with the commercial side.

Whether or not writing connects us to a world of readers and provides all the eggs that we need to feed our narcissistic impulses, the real goal is to start connecting to your own life and to what you’re really feeling and what you felt long ago and the way those feelings are echoing in the present moment. If you can’t get gratification out of that, you’re in perilous state. The process has to be the reward.

People who are older have lots more responsibilities, and that stuff bears down. The real question is, are you committed enough to make room in a very busy life? It’s on you to carve out the space to do this work, and you must take pleasure in it for itself.

Almond Extracts

- My Life in Heavy Metal (Grove Atlantic, 2002).

- The Evil B.B. Chow (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2005).

- God Bless America (Lookout Books, 2011).

Selected Nonfiction

- Candyfreak: A Journey Through the Chocolate Underbelly of America (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2004).

- (Not That You Asked): Rants, Exploits, and Obsessions (Random House, 2007).

- Rock and Roll Will Save Your Life: A Book by and for the Fanatics Among Us (Random House, 2010).

Video Clips

- Sean Hannity Gives Me Wood, Fox News, May 23, 2006.

- Steve Almond and Toto, from Tin House magazine's tenth anniversary celebration, July 16, 2009.

- God Bless America book trailer, September 2011.

See Steve Almond’s website for more about his books and “patriotic writings.”

Jim had dropped out of college, refused his share of the family loot, and apprenticed himself to an arborist. He fled as far north as he could imagine and tried to find a new, more tolerant family in the bars of south Boston. But he’d carried the old man inside him, that voice of anticipated failure, and taken it out on his girlfriends, all those sweet women turned mean with neglect. He thought of Sam, the soft flesh at the base of her neck. He thought of the trees where he hid during the day like some kind of great featherless bird bent on destruction. He thought of the last thing his father said to him before Jim stopped taking his calls: When are you going to grow up, boyo? Up above, in the dark folds of the mountain, a warbler shrieked and a second answered and then they were all going at once and then all stopped at once and the silence was hysterical. Jim missed the willows of Boston, which smelled of rain. He missed Sam.

— from “What the Bird Says” by Steve Almond