TW Review by Karen J. Ohlson

More Blue Penises? Why This Isn’t as Exciting as It Sounds

While literary fiction offers many pleasures, its readers don't usually get to experience this one: the joy of pouncing on the next book in a much-loved series. Extraordinary novels of the sort that garner nominations for the Booker Prize and its ilk are typically one-offs. Singularities. Stories complete unto themselves. Unlike genre stories, literary novels seldom end with an implied “to be continued.”

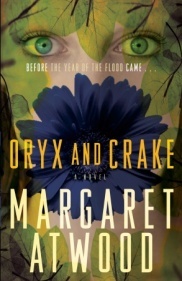

Which is why I savored the rare sense of excitement that gripped me as I opened up MaddAddam, the final volume in the recently concluded dystopian trilogy by Margaret Atwood. Begun in 2003 with Oryx and Crake (shortlisted for the Booker Prize) and continued with 2009’s acclaimed The Year of the Flood, this saga had already hooked me with its portrayal of life before and after a bioengineered plague destroys most of humanity.

Which is why I savored the rare sense of excitement that gripped me as I opened up MaddAddam, the final volume in the recently concluded dystopian trilogy by Margaret Atwood. Begun in 2003 with Oryx and Crake (shortlisted for the Booker Prize) and continued with 2009’s acclaimed The Year of the Flood, this saga had already hooked me with its portrayal of life before and after a bioengineered plague destroys most of humanity.

Not that I geek out much these days on science fiction (or “speculative fiction,” the term Atwood prefers). While I spent my high school years devouring visionary futuristic works by Hugo- and Nebula-award winning authors, I’m a literary nerd now. I want utterly convincing writing that immerses me in an experience, delivering unexpected truths. And genre writing, despite its many pleasures—thrilling plots, the satisfaction of seeing battles of ideas (in sci fi) or battles of wits (in mysteries) played out—is constrained by its conventions. Too often, those conventions prevent the writing from going somewhere truly astonishing.

Not so with Oryx and Crake and The Year of the Flood. These two books, technically part of a genre trilogy, are utterly different from each other in tone and point of view. Yet, they work together. The Year of the Flood is such a satisfying sequel to Oryx and Crake that the question urging me on to MaddAddam was not “What will happen next?” Rather, it was “How is Atwood going to top this?”

The answer is: She doesn’t.

MaddAddam offers plenty of entertaining moments, particularly in the adventurous back story of cheerful wild man Zeb (“Hi ho, hi ho / To jerkoff work I go”) and in the interactions between humans and the gene-spliced creatures that Atwood invents so engagingly: Sheep that grow human hair! Pigs with human organs and neocortex tissue! Humanoids with enormous blue penises!

However, these moments provide neither enough suspense nor sufficient literary gravitas to make this third installment a good climax to a trilogy—even a wonderfully strange trilogy that splices poetic imagery and barbed humor with an apocalyptic sci-fi message.

While the first two books are cautionary tales about humankind’s heedless destruction of the planet, MaddAddam is a cautionary tale of a different sort. It illustrates just how risky it can be trying to satisfy readers (and publishers) by extending a multi-book tale past its natural ending point.

The Accidental Trilogy

Atwood didn’t initially set out to write a trilogy. As she told an interviewer from the Powell’s Books blog in 2009, “[E]verybody was asking me what happened right after the end of Oryx and Crake. Since I didn’t know, I had to write another book in order to find out.”

Finding out, for Atwood, meant immersing herself in new characters from a different part of her fictional world and letting their story take on its own tone—not the typical approach for the middle book of a genre trilogy.

The tone of Oryx and Crake is bleak and elegiac, its point of view that of a stunned, hallucinating man called Snowman (formerly Jimmy) who may be the lone human survivor of a bio-engineered plague. But he’s not the lone humanoid. He’s the mostly hands-off caretaker of a group of genetically modified beings called the Crakers, designed (by his former best friend, Crake) to be beautiful (blue genitals and all), disease-resistant, and peacefully placid.

There are many slivers of caustic humor in this book, especially in Snowman’s perceptions of the Crakers—“a day in their company would bore the pants off him”—and in the flashback story describing his coming of age with Crake in a world run by cynical corporations. Yet, the overall mood is stark, suffused with tragedy: both the personal tragedy that haunts Snowman and the larger tragedy of humanity’s near-extinction at its own hands. The only flicker of optimism comes at the end, when (spoiler alert!) Snowman spots a small group of other humans in the distance and limps toward them, hoping he won’t have to use the gun in his hand.

In contrast, Atwood’s follow-on volume, The Year of the Flood, is much more buoyant and broadly satirical, even though it depicts the same apocalyptic future as Oryx and Crake, during the same time period. As in the first book, the narrative proceeds on two parallel tracks: one a post-plague tale of survival, the other a flashback to the characters and events hurtling toward the cataclysm.

This second installment’s lighter, warmer tone comes from the personalities of its main characters—two women named Toby and Ren, a beekeeper/herbalist and a sex-club trapeze dancer—and the narrative device around which its chapters are organized: sermons and hymns from an earnest eco-religion called the God’s Gardeners, whose leader predicted the global disaster the two women survive.

The Gardeners’ founder, Adam One, can wrap a reverent interpretation around even the grimmest of happenings. Preaching on the run, after the plague has struck, he tells his followers:

We should not have allowed Melissa to lag so far behind us. Via the conduit of a wild dog pack, she has now made the ultimate Gift to her fellow Creatures, and has become part of God’s great dance of proteins.

Put Light around her in your hearts.

Atwood pokes fun at the Gardeners, but their sincerity and practical teachings also infuse this book with hope. What Ren and Toby learn from their teachings helps them to outlast the plague and, ultimately, to help Snowman.

Both Oryx and Crake and The Year of the Flood end at roughly the same crossroads: the still point at which the feverish, crazed Snowman confronts a group of adrenaline-charged survivors—a group that includes Toby and Ren.

The first book ends with the tension of something unknowable about to happen. But the second takes the encounter farther: through danger, to danger averted, and then to a hushed, perfectly balanced moment of grace. As Ren narrates,

We listen. Jimmy’s right, there is music. It’s faint and far away, but moving closer. It’s the sound of many people singing. Now we can see the flickering of their torches, winding towards us through the darkness of the trees.

The survivors have found each other, they’ve caught and tied up the only bad guys we know about, and the healing has begun to the soundtrack of the Crakers’ ethereal singing. So, where’s the ominous drumroll of unresolved conflict for Book Three?

Resusci-Story

As I impatiently waited for the next installment, I imagined Atwood as a magician who had allowed herself to be handcuffed and locked in a box, just to show how easily she could break free: Watch me take this seemingly finished story, in which all momentum has come to a halt, and make it fling itself back into motion!

So, when MaddAdam was released to much fanfare this past September, I was ready for anything. I opened the crackling new hardcover, turned a few pages, and watched Atwood…undo the ending of The Year of the Flood.

She does it adroitly, of course. As other reviewers have noted, the way MaddAddam plays with storytelling and mythmaking is one of its strengths. From the start, her story-within-a-story approach is so entertaining it almost distracted me from worrying about the plot. Almost. MaddAddam begins (after a four-page summary of “The Story So Far”) with Toby explaining to the Crakers what has happened:

…and we caught the two bad men and tied them to a tree with a rope. Then we sat around the fire and ate the soup….

Yes, there was a bone in the soup. Yes, it was a smelly bone….

And as they were all eating the soup, you came with your torches….

You didn’t understand about the bad men, and why they had a rope on them. It is not your fault they ran away into the forest. Don’t cry.

Yes, the naïve, well-intentioned Crakers have freed the two Painballers (“This rope is hurting these ones. We must take it away.”), setting danger loose again and giving our band of plague survivors a peril to vanquish.

The problem is, these two bad guys are not worthy of an epic, end-of-trilogy battle. They are nameless and interchangeable—profanity-spewing perpetrators of casual atrocities. Vicious and sexually predatory, but in no way distinct as adversaries.

So, their shadowy presence outside the walls of the survivors’ compound doesn’t add much urgency to daily life among this book’s band of ex-Gardeners, Crakers, and scientists from a former underground group code-named “MaddAddam.” And these survivors are well enough set up—with a cookhouse, solar energy, domesticated gene-spliced animals, and a vegetable garden—that their daily challenges seem less harrowing than those faced in the earlier books.

The main narrative thrust in all three installments is in the back stories, anyway. Atwood sets up a collision course between rapacious governing corporations and the small pockets of scientists and eco-religionists trying to keep humans from wreaking irreversible havoc on the earth. The society we see in these flashbacks—scarily similar to our own—is such a rich target for her wicked humor and moral outrage, and such a strong vehicle for her message, that the tale of post-plague life seems pallid in comparison. Sure, there are some hardships, but the struggle over what was truly at stake is over: With most of the people gone, the earth has won.

Which means a trilogy-capping third volume focused on a small band of survivors was bound to face an uphill battle—even without the double expectations of readers seeking a satisfying genre and literary read.

The Plot Thins

Thanks largely to their flashbacks, Oryx and Crake and The Year of the Flood deliver what readers expect from a successful genre read: a good ride. At the same time, Atwood’s willingness to take each of these books to its own, true place—trilogy conventions be damned!—helps each to deliver what a successful literary novel must provide: a unique experience in which readers immerse themselves and emerge changed.

But as a trilogy finale, MaddAddam needs to take the story forward to work on both genre and literary terms. Readers need not just a good ride, but a race to the finish—not only a unique experience, but one that resonates across all three books.

Instead, Atwood seems to scramble to inject life into more of the same old plotting strategy. She leaps into flashback mode with eco-warrior Zeb when the survivors’ plot begins to flag. Zeb is a lively character, but his pre-plague story moves readers in the wrong direction—back, instead of forward.

Returning to the survivor story in the final chapters, Atwood throws in a host of series-ending plot staples: couples pairing off; miraculous births; and the obligatory march into battle, as a brave band of humans, Crakers, and gene-spliced animals head off to fight the Two Bad Men and their surprise hostage. However, the climactic confrontation that precedes the story’s conclusion feels muted. It’s told secondhand, in the simple words of a young Craker named Bluebeard:

And there was the sound of galloping, and footsteps with shoes on. And then it would be silent, and that was when thinking was happening. The thinking of the bad ones, and the thinking of the Pig Ones, and the thinking of Zeb, and Toby, and Rhino.

The genre reader in me felt cheated by this distance from what should be an epic clash. Even so, my inner literary nerd had to smile. Atwood may not be invested in the futuristic saga of what happens next, but at least she’s having fun with her stories-within-stories—and perhaps another deeper story.

“Please Stop Singing or I Can’t Go on with the Story”

MaddAddam is full of characters telling stories to other characters—sometimes the same one told in different ways so that the tension between versions hums beneath the surface. As Toby says to the Crakers early on in the book:

There’s the story, then there’s the real story, then there’s the story of how the story came to be told. Then there’s what you leave out of the story. Which is part of the story too.

The story left out of MaddAddam—but still hovering in the background—is how this third book in the saga came to be. Surely there were readers clamoring for another installment, including Atwood’s legion of Twitter followers (almost half a million, as of this writing) and the fans who attended her traveling-show book tour for The Year of the Flood, which featured musicians performing the God’s Gardeners’ hymns. Surely Atwood’s publicists and Random House (now part of the mega-merged Penguin Random House) must have been thrilled at the fandom potential for a third book, which eventually led to such MaddAddam promotional events as an August 2013 cruise with Atwood on the Queen Mary from England to New York.

The pressures on her to keep going must have been immense. Viewed in this context, it makes perfect sense that MaddAddam revolves around storytelling—reluctant storytelling. Toby, whose deadpan humor calls to mind the author’s own persona, gets plenty tired of her storytelling role with the Crakers:

Once Toby has made her way through the story, they urge her to tell it again, then again. They prompt, they interrupt, they fill in the parts she’s missed. What they want from her is a seamless performance, as well as more information than she either knows or can invent.

It’s no wonder that Atwood conveys the exhaustion of the storyteller so convincingly, as in Toby’s asides to the Crakers here:

In the beginning, you lived inside the Egg. That is where Crake made you.

Yes, good, kind Crake. Please stop singing or I can’t go on with the story.

When I read MaddAddam a second time, letting go of my expectations for a magnificent genre finale, I found Toby’s stories, intertwined with those Zeb tells her to tell the Crakers, to be the book’s greatest charm. For readers of Oryx and Crake and The Year of the Flood, the Craker stories are charged with irony (“good, kind Crake”—ha!). They are both serious and funny, like conversations with kids about adult topics. And, when viewed as a possible commentary on Atwood’s attitude toward stretching this saga, they take on a slyly amusing literary subtext.

Did this book need to be written? Not really. The first two balance each other out—literary twins of similar heft, like Evan Connell’s Mr. Bridge and Mrs. Bridge, or Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead and Home. Dystopian, yes; science fiction, certainly; but not plotted as the beginning and middle of a three-volume genre epic.

MaddAddam will disappoint fans who want a trilogy capper, and its half-hearted attempts to be a genre finale constrain its literary ambitions. However, when I view it as the equivalent of a bonus track or DVD “special feature”—a chance to revel in Atwood’s storytelling skills once more—I appreciate the book’s delights.

Hmm. I’m now envisioning a holiday gift-pack marketing opportunity: Oryx and Crake, The Year of the Flood, and this extra “companion volume”—plus a blue, uh, vibrating neck massager in a box. “A Craker Christmas,” anyone?

Margaret Atwood’s “MaddAddam” Trilogy

- Oryx and Crake (Anchor/Random House, 2004).

- The Year of the Flood (Anchor/Random House, 2009).

- MaddAddam (Doubleday/Random House, 2013).

Publishing Information

- “The Powells.com Interview with Margaret Atwood” by Jill Owens, PowellsBooks.Blog, October 6, 2009.

- “Who Survives, Who Doesn’t?’ An Interview with Margaret Atwood” by Isabel Slone, Hazlitt, August 30, 2013.

- “Hymns of the God’s Gardeners” by Orville Stoeber, YouTube, various dates.

- “You Can Take a Cruise with Margaret Atwood (Seriously)” by Taylor Malmsheimer, NYDaily News, April 1, 2013.

- “Book News: Penguin, Random House Complete Publishing Mega-Merger” by Annalisa Quinn, NPR, July 1, 2013.

Art Information

- Photo credit for Margaret Atwood: Jean Malek; used by permission.

Karen J. Ohlson is a senior editor at Talking Writing.

Karen J. Ohlson is a senior editor at Talking Writing.

As a longtime admirer of Margaret Atwood, Karen is amused by her own newfound kinship with the story-demanding Crakers. If only she could take on other Craker characteristics—that sunburn-resistant skin with the built-in insect repellant would be a big plus!