Essay by B. Tyler Lee

Winner of the TW 2020 "Creative Fire" Contest for Multiple Genres

The names in this piece have been changed for privacy.

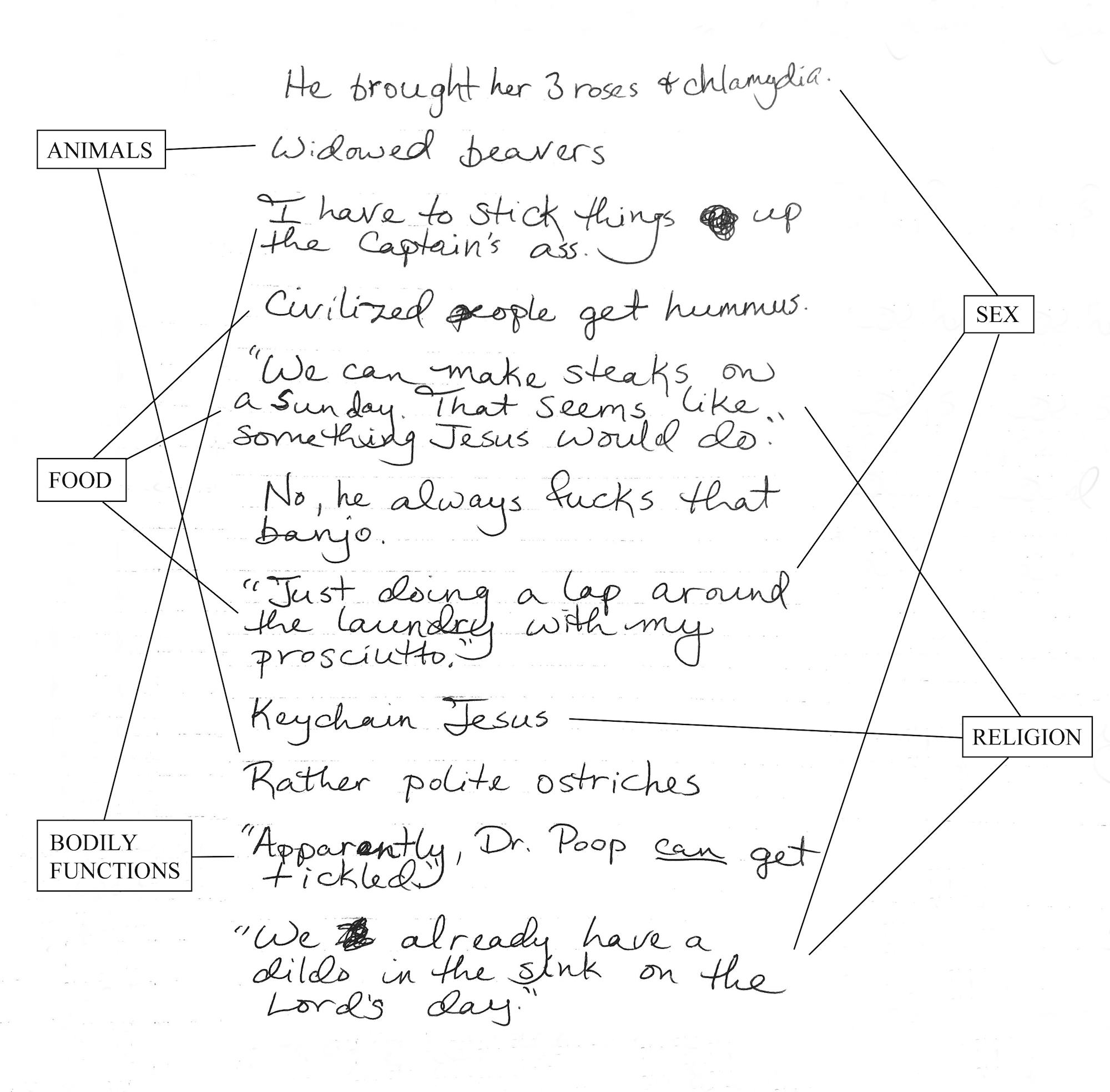

• A large volume of small nonsenses

“Sasquatch is always an option.”

I say this to my student about a plot dilemma he’s having in his supernatural novel three weeks before quarantine begins, before our ideas go to seed. Sasquatch doesn’t solve his problem, but it’s a quirky statement out of context, and he encourages me to jot it down. My students all know about “the list”: an ongoing document of language that strikes me. If the phrases aren’t mine, I ask permission to include them, so it’s mostly my own sentences peppered with contributions from my girlfriend, best friend, and two children. I turn to the list for inspiration. Whole essays and poems have spun themselves out of words plucked from the air.

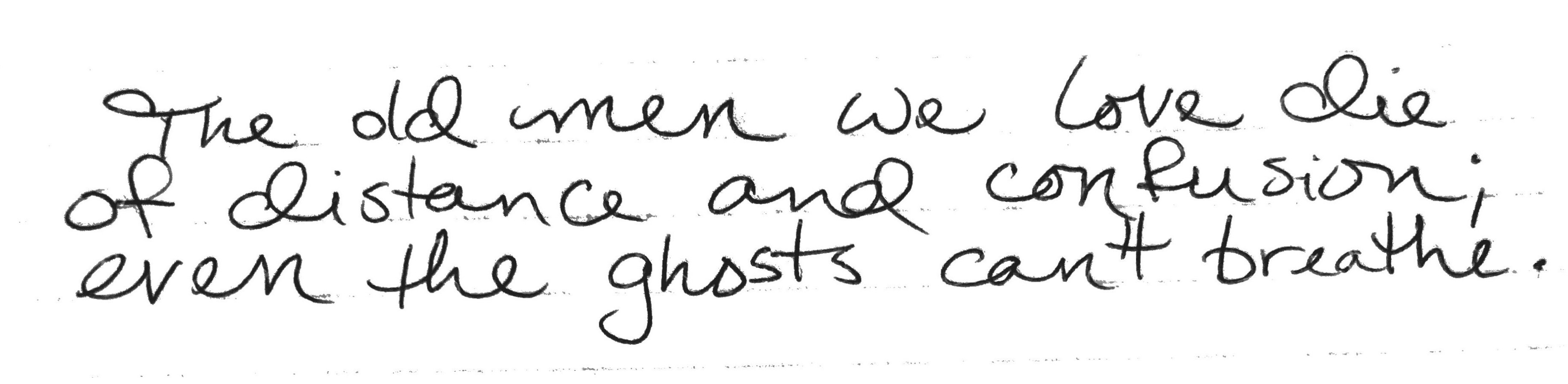

The list looks chaotic but organizes itself as you read:

The list supports my ADHD, PTSD, anxiety-and-depression-addled mom brain. Silence rarely offers itself; ideas can’t drift up. I must kidnap them, smuggle them into a moment where they make themselves useful.

• • •

As the pandemic wears on, our sentences drink themselves to stranger ground: “I’ve got one foot out the door and one breast in the news.” My girlfriend, Em, drives from Maryland to isolate with us, but still we pace and melt down. My three-year-old is potty trained, and then he isn’t. Outside the reach of school officials, my twelve-year-old, Harry, develops a twice-a-day candy habit and sprinkles “goddamn” into his speech.

We lose functions. I can’t grade or write or respond to simple emails. My girlfriend reminds me of past accomplishments—graduate degrees, awards—as evidence of my capabilities. “But that was two children ago,” I say. “My brain has since been re-formed in the crucible of turds.” Anxiety paralyzes me; I can’t even text most family and friends.

Using TV to escape the flood of work, I add:

• Closed Captioning: “[urinating forcefully]” “[The Ghost hyperventilates.]”

The latter refers to MI6’s nickname for a fictional assassin, but I’m amused the phrasing implies post-mortals can over-respire—that we’ll still need breath in the afterlife. Meanwhile, a virus steals our lungs one at a time.

We abide by the most up-to-date advice. We don’t wear masks, and then we do. I teach the toddler, Leo, to sing the chorus of his favorite song while he scrubs his hands. We sometimes hear him humming Toto’s “Africa” in the dark bathroom because he’s too short to reach the light.

• • •

• Psychology: “I’m the Jim Jones of my own interior dinner party.” “I don’t like organized pain.”

My best friend, Declan, stops appearing on the list because we can’t get coffee as we did in the Before Times, but we manage occasional phone conversations where he shares dreams: “A dying David Bowie was in your bed. And I tried to convince a dying David Bowie that we needed to flee.” He, too, finds himself immobilized these days. This comforts me; I’ve always believed him to be the better person between us.

We loved each other but have never dated. Wrong tenses: that should be present, future. We love each other. We will never date.

Em knows all this, forgives my fretting about him, understands she and I love one another in part because our lives are so complex. She has her own history to grapple with, her own emotions to push down, shake out, and ignore—though her body often tattles on her. Her hands stiffen; her face turns down for the night as if it’s being folded sharply by the universe’s housekeeper. Or she retreats into activity: racquetball, cycling; learning Italian and international law: “I’m going to do some French, too, after I read about targeted killings.”

It pains Declan to hear Em’s name. I can’t speak it, can’t indicate she exists and helps fill, beautifully, our days and two bedroom apartment, and the thought of slipping up and mentioning her flusters me to the point I stop calling him and only text.

I inflate my liferaft to support the four people I adore most: Em, Declan, Harry, Leo. The denizens of my suddenly-less-imaginary desert island. My ribcage expands and contracts around these four hearts.

Harry and Leo I love as we’re meant to love children: equally and specifically, as much for their respective obsessions with Overwatch and Baby Yoda as for the way they stubbornly refuse to be the people I wanted and expected them to be.

I never believed myself capable of loving and wishing to fully see another adult, much less two. But such differences:

Declan burns, a bitter night’s bonfire. It draws me, it warms me, but I can never lay down next to it and rest.

Em says what she thinks, crisp and forceful in the way we need. She is asshole magic. Dark genie. She grants me the ability to breathe underwater in this year of oceans.

I cannot explain this any more clearly.

• • •

• Near-Contradictions: “Preexisting Orphanhood,” “Introvert Speakeasy”

Mid-May, we transition from Hunkering Down and Waiting for an All-Clear into Quarantine as Interim Regime, standing by for whatever the cosmic oligarchy declares The Next Thing. Em returns to Baltimore; Leo throws his homemade superhero shield at the hood of her car and yells, “You stay put!” None of us wants her to leave, but we all have these new, provisional lives to lead.

A week later, we’re settling in when I wake to a text from Em: I just said goodbye to my dad; he took an unexpected turn last night…they are just “making him comfortable” now. Her sister, Elle, drives from New York to Baltimore, and they speed to Sarasota in shifts. They arrive at dawn to huddle with their mother in his hospital room, the only visitors in the whole facility. It’s Alzheimer’s, not Covid, but they thought they had months, maybe years.

She abandons the bedside vigil and calls me late afternoon, worried she’s responding incorrectly because she doesn’t want to sit and watch his lungs collapse. Em’s not a crier. In the coming weeks, she’ll by turns battle dry heaves, shiver uncontrollably, and push herself to heat exhaustion, all trying to exorcise grief from her limbs. Her mourning looks different.

Her sister comes outside to collect her; they’re going to eat, Em says. She’s been awake for almost 36 hours.

A few minutes later, she texts: He passed away while I was talking with you. Elle didn’t say anything.

• • •

The day Em’s father dies, I learn my salary for the next school year will likely be trimmed 8% while my courseload goes up, and Leo’s dad’s attorney sends papers offering me less than 20% of our shared equity in the four-bedroom home he still occupies, mostly alone.

These logistical issues stack the heartbreak deck. I worry someday Em will find herself fed up with me—my flightiness and frenetic nature, my daily tears-and-feeling-fests, my commitment to nuance so extreme I can’t even promise I’ll never want to be with anyone else—and regret having chosen to have me on the other end of the line the moment her father died.

I grieve for her: the gulf she’ll never swim across to reach him, the way we shrink our raftlines to the fewest connections we need. I want to talk to Declan, the only other adult in my rowboat besides Em, but he’s still not ready for me to speak her name.

It’s been five months since I last mentioned her.

• • •

More stacking:

Leo’s dad loses his job; even the 20% leaves the table.

U.S. streets explode with reckonings we can no longer hold at bay. We watch in horror and awe, donate, read, learn, teach the kids everything we can. Harry grows tired of talking about it, points to the fireworks on the horizon as I discuss systemic racism. I remind him he’s white and Hispanic, he’s human, he’s alive in 2020, and it’s my job as his mother to keep him from looking away. To keep either of us from turning away.

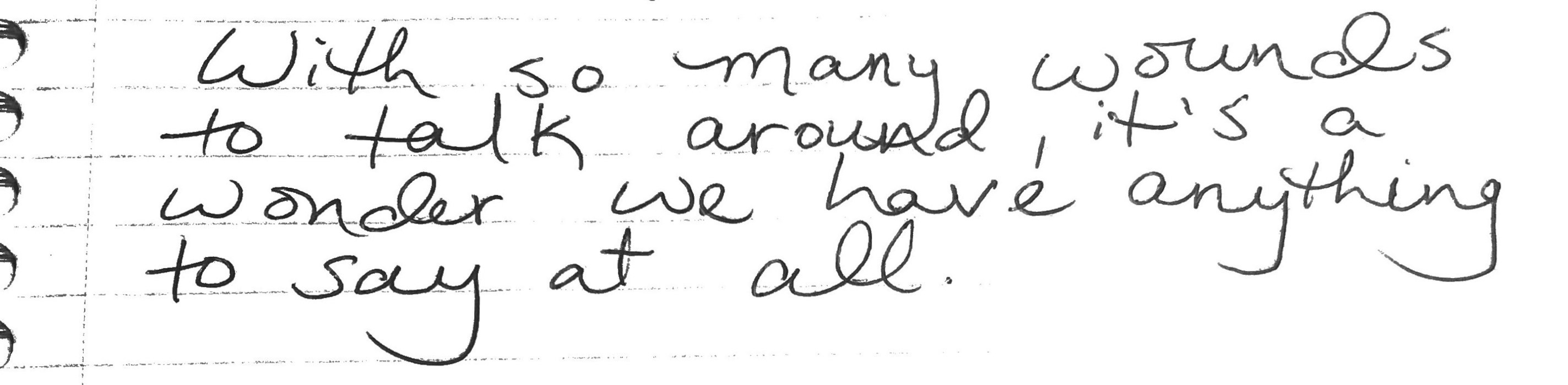

My mom and sister call in the same evening to tell me my 87-year-old grandfather, my dad’s dad, has had a stroke. It’s compounding his preexisting mild dementia, and we’ve no clue how long he has, how much function he can regain. You’d think a linguist would occupy acres of common ground with his English professor granddaughter, but aside from occasional wordplay at family events, we’ve little to say to one another. We wish it were different, but now even the words we share will no longer come out right. 1000 miles and a pandemic stretch between us. My dad, divorced from my mom and unaware she’s called, waits two more days to tell us about the stroke, via text.

• “I’m a fleet dealer of apologies.”

I’m not out of ideas, but I’m out of ways to articulate them. I’m tired: of our provisional existences, of worrying over my grandfather, of the memorials we haven’t held and won’t get to, of the way Em carried her father’s ashes home in a sustainable tote bag. Of being unable to say what I want to say to anyone but Em.

Who knows what I may tell Leo and Harry about this year in my 60s, 70s, and beyond. For now, I make a note:

Attribution Note

- Closed Captioning

- “[urinating forcefully]” is from: “Thirsty Bird.” Orange Is the New Black, season 2, episode 1. Netflix. 6 June 2014.

- “[The Ghost Hyperventilates]” is from: “Smell Ya Later.” Killing Eve, season 2, episode 5. BBC America. 5 May 2019.

- All other list items were spoken aloud and are traditional dialogue in that sense.

Art Information

- “Exquisite Corpse Puzzle” © Mercury-Marvin Sunderland and Noey Cole; used by permission.

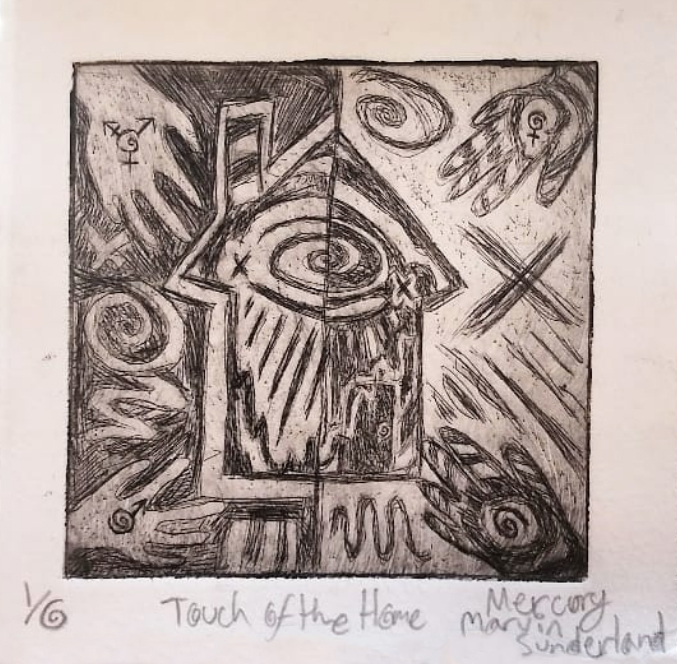

- “Touch of the Home,” “Look,” and “Trail” © Mercury-Marvin Sunderland; used by permission.

B. Tyler Lee (a pseudonym) is the author of one poetry collection, With Our Lungs in Our Hands (Red Bird Chapbooks, 2016). Her nonfiction and poetry have appeared or are forthcoming in 32 Poems, Crab Orchard Review, Hayden’s Ferry Review, Spectrum, Acting Up: Queer in the New Century (Jacar Press), Musing the Margins: Essays on Craft (Human/Kind Press) and elsewhere. Pre-COVID, she also directed community theater productions and coordinated a summer writing and arts camp for middle schoolers, both of which she hopes to resume post-pandemic. She teaches in the Midwest.

B. Tyler Lee (a pseudonym) is the author of one poetry collection, With Our Lungs in Our Hands (Red Bird Chapbooks, 2016). Her nonfiction and poetry have appeared or are forthcoming in 32 Poems, Crab Orchard Review, Hayden’s Ferry Review, Spectrum, Acting Up: Queer in the New Century (Jacar Press), Musing the Margins: Essays on Craft (Human/Kind Press) and elsewhere. Pre-COVID, she also directed community theater productions and coordinated a summer writing and arts camp for middle schoolers, both of which she hopes to resume post-pandemic. She teaches in the Midwest.

For more information, visit B. Tyler Lee on Twitter @Btylerlee7. Regarding the genesis of this unusual piece, Lee told TW by email:

All five major players in this essay have dealt with significant emotional dysregulation and sensory sensitivities throughout quarantine—and three of us are neurodivergent, to boot, though all in different ways. 2020 has thrown our already-fragmented existences into cruel relief, so this piece, for me, is fundamentally about how even a tiny wisp of language can capture a moment and give it meaning.