TW Interview by Denton Loving

An Appalachian Poet Encompasses the World

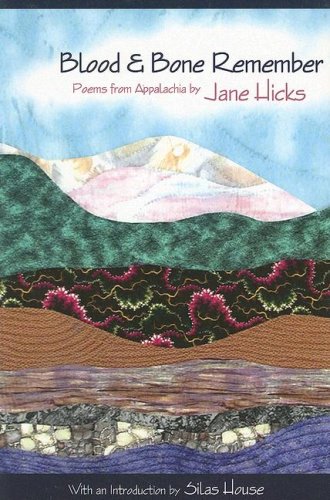

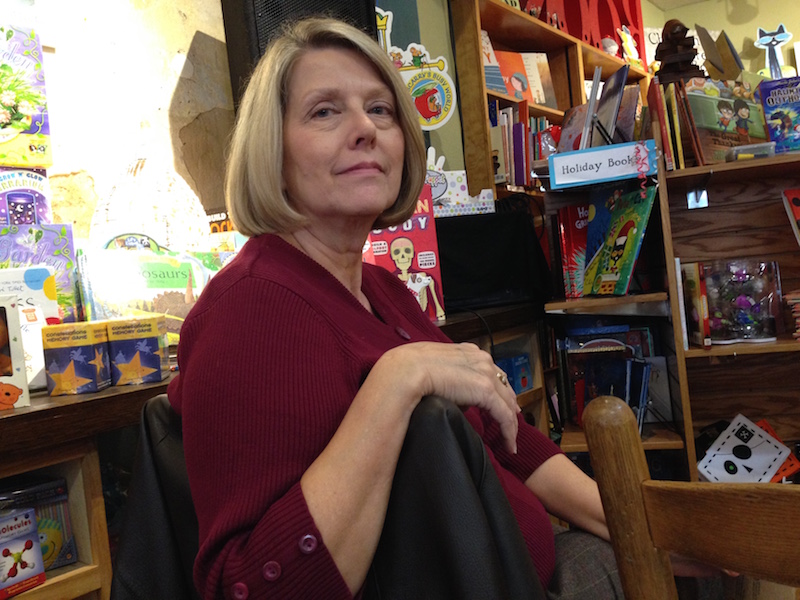

Jane Hicks—teacher, writer, quilter—has published two collections of poetry: Driving with the Dead (University Press of Kentucky, 2014) and Blood and Bone Remember (Jesse Stuart Foundation, 2005). A decade apart, both books received the James Still Award for Poetry from the Appalachian Writers Association, one of the highest honors for writing in the region.

Jane Hicks—teacher, writer, quilter—has published two collections of poetry: Driving with the Dead (University Press of Kentucky, 2014) and Blood and Bone Remember (Jesse Stuart Foundation, 2005). A decade apart, both books received the James Still Award for Poetry from the Appalachian Writers Association, one of the highest honors for writing in the region.

In the forward to Driving with the Dead, Kentucky Poet Laureate George Ella Lyon describes it as “fiercely set in Appalachia.”

Jane lives in Blountville, Tennessee. I met her in 2005, the year her first book was published, when she taught a master class in poetry for the inaugural Mountain Heritage Literary Festival at Lincoln Memorial University in Harrogate, Tennessee. (I helped establish the festival, and I'm still a co-director.) Later that summer, we also spent a week together as participants at the Appalachian Writers Workshop in Hindman, Kentucky. In 2007, she retired from the Sullivan County School District in Blountville, where she’d taught gifted and talented students for thirty years.

Over the past decade, Jane has become a friend and a mentor to me. Her poems were some of the first that drew me to writing my own poetry. Although I’ve never studied with Jane in a formal setting, she was a tremendous help as I shaped some of my first poems.

Over the past decade, Jane has become a friend and a mentor to me. Her poems were some of the first that drew me to writing my own poetry. Although I’ve never studied with Jane in a formal setting, she was a tremendous help as I shaped some of my first poems.

Last fall, I conducted this interview with Jane through a series of emails, asking her questions about the new collection and her teaching philosophy. When readers hear Jane discuss her craft—as well as her joy in leading others to write poetry—it will be clear why so many poets count her as an invaluable mentor and teacher.

This TW interview has been condensed and edited.

DL: Congratulations on receiving the 2015 James Still Award for Poetry for Driving with the Dead. What does this particular award mean to you?

JH: I’m especially grateful because this is an award given by peers. They understand what it means to be from and write about the region. It was my intention that this book be not an Appalachian book but a book written by an Appalachian.

DL: What’s the distinction between those two?

JH: I mean that the topics speak to general human themes and situations, not just Appalachian themes. The war poems especially relate to any area of the country in that time period. Many of the poems don’t express a specific location, but the ones that do can be militantly Appalachian.

DL: I’m glad you mentioned the war poems. Why do you think war became such a prevalent theme in Driving with the Dead?

JH: I’m from a generation that has never been long without war. My father and grandfather were veterans of Korea and World War I, respectively. I grew up during the Cold War, no less taxing on the psyche, and my generation was the Vietnam generation. While I was writing this book, one of my best readers was a career army officer. The Vietnam poems fascinated him. He was thrilled the book was to be published, but sadly, he didn’t live to see that happen.

DL: In “Draft Lottery,” you appear as a character waiting to find out if your boyfriend will be sent to fight in Vietnam. The poem is set on July 1, 1970. Do you remember how long it took after that date to write about it?

JH: Forty-four years. The characters are all compilations of people I grew up with, but the draft lotteries were very real. I had a woman accuse me of lying about them, and she claimed our country would never do anything like that. But I can see people nodding their heads in the audience when I read that poem. It’s always on my reading list when I do anything on a college campus, and I encourage students to read about this period in history. I allude to something they understand when I say, “May the odds be ever in your favor.”

DL: So, poetry can be used as a vehicle for learning about history.

JH: I’m a teacher at heart. I want to inform and remind students that history didn’t happen in a vacuum and is not confined to events in history books. The people who fought in Vietnam or protested against it (or other conflicts and wars) are right here, and students can talk to history.

I recently read at a nearby university, and some of my former students were present. As I read that poem, I could see them nodding and prodding each other. We studied the draft lottery in our class, and they remembered. They also had a reaction to a poem from my other book that talked about the Cold War. Someone asked me a question about the draft lottery after the reading. As the crowd left the auditorium, I saw one of my students talking to this person. I’m confident she set that person in the right direction to learn more.

DL: Another poem where you address the political through the personal is “Black Mountain Breakdown.” The title is a reference to a 1980 novel by Lee Smith, but the poem is about a three-year-old boy, Jeremy Davidson, who was killed in 2005 when a boulder from a strip mine crashed through his home. How did you come to write about Jeremy’s death?

JH: The title refers to the fiddle tune “Black Mountain Rag,” Led Zeppelin’s “Black Mountain Side,” and the name of the mountain where the illegal strip mine loosed the boulder that killed Jeremy. The title of Lee’s wonderful book perfectly describes the breakdown of the mountain. The nod to the fiddle tune sets the place. As for the Led Zep reference, that title was in my head.

I was very familiar with the place Jeremy lived. When I met my husband, he was actually working on Black Mountain at a government facility. It was very beautiful there, and we often drove up that way. There was once a tiny post office at Inman, where the Davidson family lived. The scene those names recalled was so pastoral that this tragedy seemed almost surreal. I was so incensed that a baby be lost this way. The family moved, and the older brother, who was spared, was in the classroom next door to mine. I saw him every day. His face haunted me.

DL: “A Poet’s Work,” another poem dedicated to Jeremy Davidson, feels a bit like a manifesto about the poet’s responsibility, which you describe as “the naming of what matters.” I particularly love these lines:

Witness meth labs that spring up in our rural

gardens, a quick payout or fuel for three

piddly jobs, two to live, one to pay daycare.

Clutch the child who sobs silently,

her mama a nurse in the Guard, called up,

goodnights a webcam image from Basra.

Behold mountaintops removed, laid low by greed,

hollows filled, wells poisoned, God’s majesty

flattened, fit only for Wal-Mart, the new Ground Zero.

The lines feel instructional, as if you’re saying this is precisely how poets should be interacting with their communities. Do you think this approach allows the work to be more accessible to the common reader?

JH: Yes. I couldn’t sum it up any better. I try to write poetry that reaches across disciplines and levels of education. I’ve been at the foot of the ivory tower, but never in it. One of my greatest compliments came when a student told me her father (a coal miner) had borrowed my first book from her and read it so much that she needed her own copy. I gave her one.

DL: I don’t want to acknowledge the loss in your poems without also recognizing the humor and joy. Is it difficult to straddle that line?

JH: I try very hard to be specific about things I have observed in life. Unless one has lost all joy, there is humor in everyday life. These things bear remembering and witnessing.

DL: One of the funniest poems in the collection is “Domestic Arts,” in which the narrator’s mother and grandmother use their sewing skills to take revenge on their roaming men. I’ve heard you say that this poem is fiction. I believe I’ve also heard you say that a poet should never let the truth stand in the way of a good poem. How does this philosophy work when the poet is also looking at the problems of society and politics?

JH: “Domestic Arts” is fictional, but I did hear a similar story when I was a young girl. The old women used to tell it in reference to a particular couple in the community, so I believe there is a grain of truth in it. The couple in question was already quite elderly by the time I heard the story, and it amused me to even think of him dancing up a storm, much less his clothes flying to pieces.

By the time I wrote this poem, I realized that the woman in the story had few options in her life to fight back against the man’s infidelity. Men did what they pleased and treated their families as they pleased. She fought back the only way she could. I hope she really did it. I extrapolated the second verse and placed it in the disco years—a complete fiction. I gave that woman a weapon.

DL: I know that Gerard Manley Hopkins is one of your favorite poets. Your introduction to his poetry (when you were in the second grade) is described in a poem in Driving with the Dead. How has his work influenced your own?

JH: I love his sprung rhythm and believe it crops up in my work from time to time. His particular way of naming and describing things also sneaks into my poems. There is a joyousness in his naming. This particular poem ("My Second-Grade Teacher Reads Gerard Manley Hopkins") is included in an upcoming anthology celebrating the work of Hopkins.

DL: You’ve taught creative writing to school-age children and continue to teach poetry workshops to adults at all stages in their writing. What are some of the biggest blocks in learning to write poetry?

JH: The biggest block to overcome is self-criticism. Most adult students find it too hard to let go and write. Where younger students often hesitate to edit, adults start editing before the pen hits the paper. Then there is the reverse—poets who won’t edit and believe every word is divine inspiration. It’s a fine line to walk with both types in class.

I like to do generative classes with lots of prompts. We do fast writes, a little sharing, and move on to the next prompt. That way, the writers don’t have too much time to think and censor themselves. As other participants share, this kicks off a chain reaction of creativity. I try to keep them on the creative side of the brain.

DL: Besides your work as a writer, you’re also a fiber artist. The cover of Blood and Bone Remember is an image from one of your quilts. How do these art forms work together for you?

JH: When I'm quilting, I keep a journal by the quilt frame. Doing handwork of any kind keeps one on the creative side of the brain and lets what I call “the random rabbits of thought” pop up. I jot down ideas and return to them later. It keeps me from thinking too hard and editing as I write. I have a poem about this in my first book.

DL: How have your writing practices changed over the years?

JH: When I was teaching, I wrote whenever I could steal time. Most of my creativity was taken up in teaching. I wrote mostly in the summer and during writing workshops. Now, I try to write every day. However, I set a goal of writing five days a week. If I have days where writing is not possible, I don’t feel I fell short.

I'm a morning writer. If I don’t get up early and start, it’s hard for me to get my ideas out before they become too organized and rational. I can edit and read later in the day, but creative efforts take an early start. I do count reading and editing as writing, by the way.

DL: Since the publication of Driving with the Dead, you’ve been writing a series of poems about angels. Where did that interest come from?

JH: In December 2003, my mother was in a serious automobile accident and in a coma for seventeen days. After fifteen days, things became grim, and we thought she would never regain consciousness, but she did. When she became able to communicate, she related a near-death experience, describing exactly what happened at her bedside on that fifteenth day. She told several people about it. The most remarkable thing is that my mother was a very no-nonsense, practical person. Before that time, she would have laughed at any such notion. The details she gave about angels became the basis for my first poem.

I started researching angels across several religious disciplines, finding more similarities than differences. I'm still working on what Judeo-Christian tradition would call archangels, and I hope to branch out. I particularly want to examine how Milton’s Paradise Lost has colored our modern notion of angels.

DL: Do you have a favorite angel?

JH: At present, my favorite is Metatron. I read about him in Jewish mystical writings. In some traditions, he is Enoch, who was taken up without dying and became an angel. This falls far outside the realm of anything I thought I knew about angels. I’m still trying to finish his poem. It’s difficult to find entry into some of these poems without being too didactic. The teacher in me struggles not to write lessons with all I have encountered in my research.

For more information about Jane Hicks, see her website The Cosmic Possum.

The lines from "A Poet's Work" are from her book Driving with the Dead, published in 2014 by the University Press of Kentucky.

Denton Loving is the author of the poetry collection Crimes Against Birds (Main Street Rag, 2015) and editor of Seeking Its Own Level: An Anthology of Writings About Water (MotesBooks, 2014). Follow him on Twitter @DentonLoving.

Denton Loving is the author of the poetry collection Crimes Against Birds (Main Street Rag, 2015) and editor of Seeking Its Own Level: An Anthology of Writings About Water (MotesBooks, 2014). Follow him on Twitter @DentonLoving.