Theme Essay by Elizabeth Langosy

Sucking the Soul out of a Classic Novel

Quick! Name the book that begins like this:

Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again.

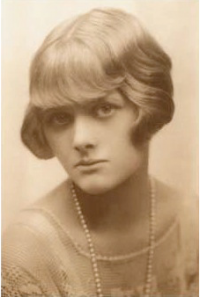

Yes, dear readers, it’s Rebecca, Daphne du Maurier’s 1938 novel and one of my personal “stranded on a desert island” picks. Sinking into that sentence—and the ones that follow in the brief first chapter—is like sharing a close friend’s confidences or exploring the journal of a beloved, long-gone relative.

Yes, dear readers, it’s Rebecca, Daphne du Maurier’s 1938 novel and one of my personal “stranded on a desert island” picks. Sinking into that sentence—and the ones that follow in the brief first chapter—is like sharing a close friend’s confidences or exploring the journal of a beloved, long-gone relative.

In fact, the entire book is a glimpse into the narrator’s psyche, which makes it perfect material for an Alfred Hitchcock movie—or so you'd think. Over the years, I've watched many filmed adaptations of Rebecca, and almost every one has undermined du Maurier's novel. How laughably off-track they've been provides a good case study of why some books are not easily translated to film.

I discovered Rebecca when I was a shy and solitary teenager, newly acquainted with the joys of gothic novels. I devoured the works of Victoria Holt, Mary Stewart, and other writers whose heroines all seemed to start out as live-in governess to the children of a young widower and go on to become mistress of the manor. The manor was always located on the stormy coast of Cornwall. The widower was always broodingly handsome and haunted by the death of his wife.

The thought that I could one day be that governess—on my own in a new place, without my family, heroically making a new life—got me through many a lonely evening. If the heroines whose bereft lives seemed so similar to mine were able to reach their full potential in such a dramatic way, I could, too.

When I worked my way through the library shelves to Rebecca, I realized within a few pages that this was not a gothic novel, despite the dramatic cover image of Manderley, a manor house by the sea, and the character of Maxim de Winter, a striking man grieving the recent death of his wife, Rebecca.

In Rebecca, the young heroine becomes Maxim’s new wife and the mistress of the manor before she realizes what’s hit her. A girl so inconsequential to the world she inhabits that her given name is never mentioned, she’s drawn by love into a situation that highlights her lack of worldliness at every turn.

In Rebecca, the young heroine becomes Maxim’s new wife and the mistress of the manor before she realizes what’s hit her. A girl so inconsequential to the world she inhabits that her given name is never mentioned, she’s drawn by love into a situation that highlights her lack of worldliness at every turn.Even her description of herself is significant: “straight, bobbed hair and youthful unpowdered face, dressed in an ill-fitting coat and skirt and a jumper of my own creation.”

Du Maurier shows not only the trappings of the haut monde that surround (and flummox) the new Mrs. de Winter, but also the complexity of her inner thoughts. And these thoughts are the soul that’s been sucked out of nearly every subsequent incarnation of Rebecca.

Here's the young wife in the book, fantasizing about an alternate life with Maxim as they travel to Manderley after meeting and marrying in Monte Carlo:

...Maxim could lean over a cottage gate in the evenings, smoking a pipe, proud of a very tall hollyhock he had grown himself, while I bustled in my kitchen, clean as a pin, laying the table for supper. There would be an alarm clock on the dresser ticking loudly, and a row of shining plates, while after supper Maxim would read his paper, boots on the fender, and I would reach for a great pile of mending in the dresser drawer.

Other young women—say, the characters in the novels by Victoria Holt—would be dreaming of the mansion they'd inhabit and the tea served on a silver platter by the butler.

Du Maurier created terrific characters out of a sentence or two. Here’s her depiction of the wealthy American Mrs. Van Hopper, who has hired our heroine as a companion at the start of the book:

She would precede me into lunch, her short body ill-balanced upon tottering, high heels, her fussy, frilly blouse a compliment to her large bosom and swinging hips, her new hat pierced with a monster quill aslant upon her head, exposing a wide expanse of forehead bare as a schoolboy’s knee.

And here’s the first glimpse of the terrifying Mrs. Danvers, housekeeper of Manderley:

Someone advanced from the sea of faces, someone tall and gaunt, dressed in deep black, whose prominent cheek-bones and great, hollow eyes gave her a skull’s face, parchment-white, set on a skeleton’s frame.

The housekeeper undercuts the new Mrs. de Winter at every turn, while constantly reminding her that Rebecca was on top of everything from the most suitable accompaniment for roast veal to the appropriate attire for a ball. In one eerie scene, depicted in all the filmed versions, Mrs. Danvers describes how she prepares a now-unused bedroom for her former mistress each evening, removing Rebecca’s nightdress from its embroidered case and arranging it lovingly on the bed.

Shortly after the publication of Rebecca, du Maurier herself adapted it as a stage play that appears (from snippets available on Google Books) to begin when Maxim and his new wife arrive at Manderley, rather than in Monte Carlo. In 1940, the play had a successful London run of over 350 performances. The same year, Hitchcock’s Academy Award-winning film version was released in the United States.

Hitchcock cast Joan Fontaine in the role of the young wife. With her flirty smile and curled hair, she seems to be constantly biting her cheek to remind herself that she’s meant to be shy and unworldly. Laurence Olivier makes a dashing Maxim de Winter, perfectly in keeping with du Maurier’s description, but Judith Anderson looks nothing like the skeletal housekeeper described in the book. She does act creepy, though.

Hitchcock cast Joan Fontaine in the role of the young wife. With her flirty smile and curled hair, she seems to be constantly biting her cheek to remind herself that she’s meant to be shy and unworldly. Laurence Olivier makes a dashing Maxim de Winter, perfectly in keeping with du Maurier’s description, but Judith Anderson looks nothing like the skeletal housekeeper described in the book. She does act creepy, though.

I loathe the beginning of the movie, which offers a truncated version of the opening lines, intoned in Fountaine’s too-sophisticated voice, as the camera sweeps down the overgrown drive leading to Manderley. In one of many other fabricated scenes, our heroine rescues Maxim from an intended suicide jump that conveniently occurs at the spot where she sits sketching in the middle of nowhere.

The Hitchcock movie marked the beginning of Rebecca as ghost story. (If you can’t depict the inner torments of a character, you must invent some external ones.) The package copy of the DVD I recently borrowed from the library warns the viewer, complete with dramatic bolding and capitalization:

After a whirlwind romance, MYSTERIOUS WIDOWER Maxim de Winter brings his shy, young bride home to his IMPOSING ESTATE, Manderley. But the new Mrs. de Winter finds her married life dominated by the sinister, almost spectral influence of Maxim’s late wife: the brilliant, ravishingly BEAUTIFUL Rebecca, who, she suspects, still rules both Manderley and Maxim from BEYOND the GRAVE!

The even more absurd 2003 Masterpiece Theater production appears to be based on Hitchcock’s film rather than on the book. The two-part series begins with Masterpiece host Russell Baker informing viewers that they’re about to see “the most popular ghost story to come out of England since Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol.” Then he portentously adds: “At the center of the story is a haunted house.”

Ah, Manderley. How far you have strayed from your noble beginnings. You are now possessed by Rebecca—or at least by her enormous head, whose staring eyes and plucked eyebrows fill the screen whenever there’s a hint of trouble or doom.

Ah, Manderley. How far you have strayed from your noble beginnings. You are now possessed by Rebecca—or at least by her enormous head, whose staring eyes and plucked eyebrows fill the screen whenever there’s a hint of trouble or doom.

In this PBS television incarnation, our heroine’s opening dream of Manderley is dropped altogether in favor of the fabricated cliff-side sequence of the distraught Maxim and his artistic bride-to-be. The scene cuts to a stormy sea with a capsized boat that’s quickly replaced by Rebecca’s monstrous eyes. Trouble’s ahead!

By the time they’re back in Monte Carlo and Mrs. Van Hopper appears, all is lost. Rather than the figure described by du Maurier—with her large bosom, swaying hips, and broad forehead—Mrs. VH is played by Faye Dunaway. A fairly sexy Dunaway, too, who flirts with Maxim rather than just trying to ingratiate herself with a European aristocrat, as the book’s Mrs. VH does.

Charles Dance looks nothing like du Maurier’s description of Maxim, and Emilia Fox—although possessing the requisite bob—is altogether too self-possessed as our heroine. In scenes created just for this production, Maxim and his future bride cavort in the ocean, go boating, laugh, and cuddle. Back at Manderley, even Diana Rigg’s acting prowess—she won an Emmy for her role—cannot compensate for her inappropriateness for the role of Mrs. Danvers.

Oh, send me back to the wonderful 1979 BBC production of Rebecca, the one that’s so mired in rights issues that it never has come out on DVD, the one you can only glimpse in pirated YouTube videos. I first saw it when it appeared on Masterpiece Mystery in March 1980 and have futilely sought a copy of it ever since. Although this adaptation takes four hours to tell the story, it replicates as closely as possible du Maurier’s depiction of the characters and events.

At the start, our heroine is sitting over tea, sharing her dream and subsequent thoughts with an unseen friend (much as they’re shared with readers of the book). Joanna David plays the part of the young bride to perfection, right down to her outmoded clothing and hesitant manner. Elspeth March is stout and overbearing as Mrs. Van Hopper, Jeremy Brett gives an outstanding performance as Maxim, and Anna Massey is brilliant as Mrs. Danvers. Although Rebecca’s presence lingers everywhere—in the “R” that embellishes napkins and stationery, the positioning of the floral arrangements, and the special sauces served at dinner—there’s not a spectral eyebrow to be seen.

At the start, our heroine is sitting over tea, sharing her dream and subsequent thoughts with an unseen friend (much as they’re shared with readers of the book). Joanna David plays the part of the young bride to perfection, right down to her outmoded clothing and hesitant manner. Elspeth March is stout and overbearing as Mrs. Van Hopper, Jeremy Brett gives an outstanding performance as Maxim, and Anna Massey is brilliant as Mrs. Danvers. Although Rebecca’s presence lingers everywhere—in the “R” that embellishes napkins and stationery, the positioning of the floral arrangements, and the special sauces served at dinner—there’s not a spectral eyebrow to be seen.

This splendid adaptation comes closest to my vision of Rebecca, yet I can’t help thinking of one particular line of dialog that appears in all the versions. As Maxim and his bride drive up to Manderley, he tells her, “Just be yourself, and they’ll all adore you.” In the movie and TV versions, these are the words of a loving and supportive husband reassuring his young wife. In the book, they take on sinister overtones, because readers know exactly how the heroine sees herself, and it’s not as someone who would be adored:

I did not answer him, for I was thinking of that self who long ago bought a picture postcard in a village shop, and came out into the bright sunlight twisting it in her hands, pleased with her purchase, thinking, ‘This will do for my album. “Manderley,” what a lovely name.’ And now I belonged here, this was my home.... I would walk along this drive, strange and unfamiliar to me now, with perfect knowledge, conscious of every twist and turn, marking and approving where the gardeners had worked, here a cutting back of the shrubs, there a lopping of a branch, calling at the lodge by the iron gates on some friendly errand, saying 'Well, how's the leg today?' while the old woman, curious no longer, bade me welcome to her kitchen....

It seemed remote to me, and far too distant, the time when I too should smile and be at ease, and I wished it could come quickly, that I could be old even, with grey hair, and slow of step, having lived here many years, anything but the timid, foolish creature I felt myself to be.

Publishing Information

- Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier (Victor Gollancz, 1938; first American edition: Doubleday, 1938).

- Rebecca: A Play in Three Acts by Daphne du Maurier (Samuel French, 1939).

“Maybe it’s just a matter of semantics. Does it shift the paradigm if a film is called a “retelling?” Am I more comfortable with “influenced by” or “based on?” When does an “adaptation” become a new creative work altogether?" — "It’s a Book! It’s a Movie! It’s a…Zombie?"