TW Review by Fran Cronin

Will the Real Joyce McKinney Please Stand Up?

Errol Morris knows how to provoke big questions with a small tale. For more than thirty years, this quirky filmmaker has chronicled the prosaic as well as the powerful. With the aid of his “Interrotron”—a video device that lets Morris and his subjects look at each other while also looking into the camera—we feel ourselves peering into the hidden worlds of death row inmates, lion tamers, robots, naked mole rats, a designer of electric chairs, and people who cut off their legs for insurance money.

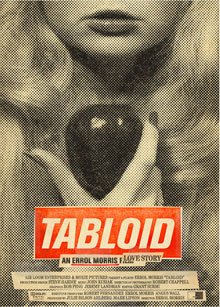

It’s a brilliant, eccentric, and voyeuristic approach, to be sure, which makes it extremely fitting that Morris’s eleventh documentary delves into that most voyeuristic of journalistic media—the tabloid and its raucous relationship with truth.

It’s a brilliant, eccentric, and voyeuristic approach, to be sure, which makes it extremely fitting that Morris’s eleventh documentary delves into that most voyeuristic of journalistic media—the tabloid and its raucous relationship with truth.

Given the scandal erupting around Rupert Murdoch’s tabloid empire when the film was released this summer, Morris’s timing couldn’t have been better. His Tabloid is captivating and titillating.

But precisely because tabloid sensationalism and a loss of personal boundaries continue to lord over the media—and have huge consequences for how much we trust what we’re told—I wondered if a documentary film about this topic can get away with letting subjects speak for themselves.

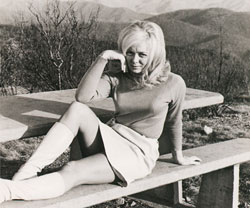

Tabloid dissects the bizarre saga of blonde and kittenish Joyce McKinney, a former Miss Wyoming, who in 1977 catapulted to British tabloid fame in the infamous “Case of the Manacled Mormon.” Like the recent Arnold Schwarzenegger “love child” scandal, prurient interest in McKinney kept the tabloids bristling on both sides of the Atlantic.

The object of McKinney’s ardent affection was an errant Mormon by the name of Kirk Anderson. When Anderson was shipped off to London by the Latter-day Saints as a missionary, McKinney insisted the church had brainwashed him away from her and concocted a scheme to win him back. Her ascent as a tabloid darling began with her alleged kidnapping and “rape” of Anderson—supposedly manacled to a bed—for three days in an English farmhouse.

McKinney famously said at the time, “I loved him so much that I would ski naked down Mount Everest with a carnation up my nose if he asked me to.” Perhaps for obvious reasons, this failed to rekindle his love.

The British police alleged that, after spending three months on remand in prison, McKinney jumped bail and fled to Canada, wearing a red wig and posing as a deaf-mute mime artist.

Like any good piece of yellow journalism, the story is surreal and entertaining. But I’m troubled by the narrow focus of Tabloid. Unlike Morris’s singular Fog of War, which dealt with one of our nation’s most tragic foreign policy decisions, his latest film zeroes in on the frolicsome and self-absorbed McKinney. We feel smug, enjoying her antics yet knowing how tacky they are. But like tabloids themselves, that’s a cheap thrill.

Tabloid is a classic Morris mash-up of newsreel footage, graphics, and interviews. He cuts between past and present, allowing his subjects to play out their gossiping and confessional one-upmanship. Retro pasteups animate McKinney and her accomplices’ comings and goings across England and beyond.

The two tabloid journalists who competed for McKinney headlines and scoops back in the ‘70s, Kent Gavin and Peter Tory, stalk the story like hunting dogs waiting to pounce. One of them muses, “Was it chains or ropes she tied him with?” Must be chains, he determined, it sounds better.

In an interview about Tabloid for the 2010 Toronto International Film Festival, Morris describes McKinney as his favorite protagonist. Not because he finds her endlessly interesting, he says, but because she’s emblematic of our human capacity for self-delusion.

In a line reminiscent of Bush-era doublespeak, McKinney herself says in Tabloid, “If you tell a lie enough times, you come to believe it.”

She doesn’t come across as a credible witness to her own story, but what resonates is the ferocity of her self-deception. She’s so convinced of her revisionist retelling that, from her perspective, you could say McKinney never genuinely lies.

Instead, what we’re left with is her zealous pursuit of the deeply felt gesture. In addition to the Anderson affair, she made illegal attempts to raise funds to purchase a false leg for her three-legged horse; she cloned her beloved dog, Booger, with the aid of a Korean scientist. Sensational headlines have followed in McKinney’s wake like dust to Pig Pen in a Peanuts cartoon.

I judged her and wanted to write her off. Yet, McKinney possesses a goofy earnestness you can’t dismiss. She’s like the harmless, out-of-touch cousin from your mother’s side of the family. She’s entertaining, but you never know what to believe.

As for Morris, he doesn’t let on how he feels about McKinney’s motives. The closest he comes to commentary is when he shares the poignant videos McKinney made of herself while in self-imposed exile after the “Manacled Mormon” debacle. Alone, looking out over the tall, windblown grass surrounding her family’s farmhouse, McKinney muses on the nature of true and eternal love, vowing to write a book.

Like many of Morris’s other subjects, she wraps herself in a reality of her own making. It’s both a fascinating and disturbing performance. However, unlike the convoluted earnestness of Fred A. Leuchter, Jr., whom Morris chronicled in Mr. Death, McKinney seems to have no greater ambition than to market her fantasies.

I’ve always thought of Morris as a filmmaker who strives for moral high ground, not just cinematic sport. But by not offering his own view of McKinney, he’s a bit disingenuous, and his obvious enjoyment of her as a cause celebre seems to have blunted his usual edge. If the Murdoch saga indicates nothing else, it’s that we live in a world of self-deceivers. They often justify themselves by saying they’re just giving the public what they want.

I’ve always thought of Morris as a filmmaker who strives for moral high ground, not just cinematic sport. But by not offering his own view of McKinney, he’s a bit disingenuous, and his obvious enjoyment of her as a cause celebre seems to have blunted his usual edge. If the Murdoch saga indicates nothing else, it’s that we live in a world of self-deceivers. They often justify themselves by saying they’re just giving the public what they want.

I confess to enjoying a little dose of the Kardashians or Brangelina when in the grocery checkout line. But I didn’t like observing McKinney’s vulnerability on screen, and I didn’t like being a voyeur, especially if the point of the film is to put her wanton self-deception on display. Alone in the frame, McKinney seems like the kid in high school who thinks she’s popular when she’s really being mocked.

She glows under the trained lights of Morris’s camera. But when the house lights come up, she, like the film, fades to black. Like a confection, there is delight in the eating, but then the sensation melts away.

Recently, there were rumors that McKinney had made an unannounced appearance where Tabloid was being screened. Two women stopped me as I exited from my local cinema.

“Excuse me,” one said hopefully, “but we were wondering. Are you Joyce McKinney?”

Publishing Information

- “Errol Morris: Tabloid,” interview for 2010 Toronto International Film Festival with Nick Wilson.

- See Errol Morris's website for more information about the filmmaker and his movies.

Art Information

- Tabloid poster and Joyce McKinney photo; press images

- “Errol Morris in 2011″ © Nubar Alexanian; GNU free documentation license

Fran Cronin is a contributing editor for Talking Writing.

Fran Cronin is a contributing editor for Talking Writing.

"To paraphrase Groucho Marx and Woody Allen, I only belong to clubs no one else wants to join. Maybe that’s why I feel so drawn to literary accounts by other reluctant members of the widows club." — "Widow Books"