Essay by Martha Nichols

Reassessing Grief in a Pandemic

March 16, 2020

At first, Harvard Square seemed deserted. Where Bow and Arrow Streets hit Mass. Ave., storefronts were shuttered. Grafton Street Pub. Hokkaido Ramen. My son and I parted ways to do quick errands—me to deposit a check, him to complete his mission at a favorite jewelry store.

My eighteen-year-old had been planning this stop for weeks. He’d had his eye on a silver ring he wanted as a reward for passing his driving test. The test was scheduled for this Monday afternoon, but as we’d just discovered—via signs posted on its smeary plate glass in nearby Watertown—the Registry of Motor Vehicles was closed.

Not surprising, in hindsight, after Governor Charlie Baker’s announcement the night before that all government agencies would shut down except for essential services. All restaurants in Massachusetts were supposed to close by Tuesday, too, except for takeout service. My son was already grumbling about what that would be like during his next shift at Starbucks.

He was starting to shrug off the store closures. His high school had closed the previous Friday, and that was okay. When I asked, he said he really didn’t mind if he missed his senior prom or his graduation ceremony, although I didn’t believe him.

But no driving test? He was furious at the RMV. Just that morning, he’d paid for his test on the RMV website, and there was NOTHING about the test being canceled or about the office being closed and how hard is it to update a website??

Hard, I said, if you’re a bureaucracy in an emergency. That went nowhere. I told him he’d just joined every human being on the planet in hating the RMV. This gallows humor fizzled, too.

Humor is a go-to defense in our family when things go wrong, but so much is wrong now. I later realized my son needed more than a joke from me, even if I often see him as an adult. As the coronavirus crisis continues to unfold, maybe we’re all kids who want our parents to make it better. At least we can allow ourselves a few moments of wailing and longing.

So far, it’s been First World problems for us. In better times, my sharp snarky boy, my Vietnamese adoptee, would have pinned me to the wall for similar complaints. As he drove us over to the RMV, he’d reminded me I wouldn’t be going on the test with him. He didn’t want my nervousness or intensity rubbing off on the evaluator.

When he asked to go to Harvard Square anyway—I’m angry, I need to make myself feel better—I agreed, although the last thing I wanted was to roam around in a public place. He beelined for the jewelry store, saying he’d meet me at the bank.

I'll be faster than you, Mom.

I headed into the cold wind down Mass. Ave., noting only a few passersby and cars on the street at rush hour. At rush hour? There were empty buses lined up. I’d been beating back my own sadness for days, but the chilly loneliness of an urban tourist spot with no people brought a whiff of despair, which was worse. I imagined cardboard boxes or tumbleweeds blowing down the avenue, as if the apocalypse had already happened.

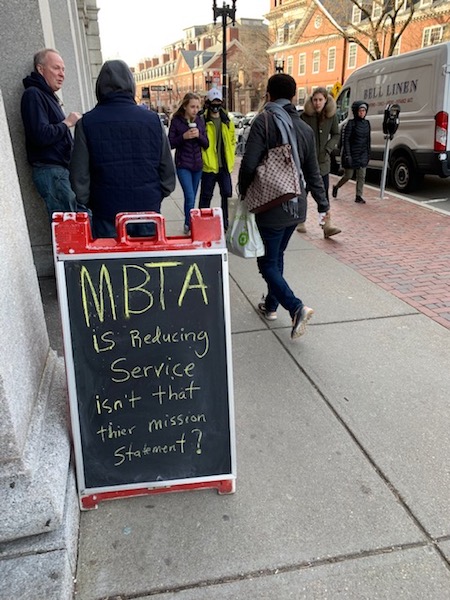

Then I saw the handwritten sign outside Mr. Bartley’s Burgers: MBTA is Reducing Service isn't that thier [sic] mission statement?

The MBTA—aka “the T”—runs the Boston area subway and bus system. Even under normal circumstances, it’s a favorite target. Complaining about the T is right up there with going after the Red Sox when they screw up.

The MBTA—aka “the T”—runs the Boston area subway and bus system. Even under normal circumstances, it’s a favorite target. Complaining about the T is right up there with going after the Red Sox when they screw up.

My despair clicked off. I deposited my check at the ATM, then came back up Mass. Ave., and suddenly there were people—not just the old guy in a wheelchair and a watch cap outside my bank, talking to himself about a lost love. Some wore masks, but not all, and couples and trios ambled around me. For two blocks, a horizontal rank of four young women was hard to keep any social distance from. Their pink and yellow down jackets looked like Easter eggs.

And this time, I stopped to take a picture of the sign outside Bartley’s, where two older guys with thick Boston accents were now chatting. As I snapped away, they looked up.

“Smile!” I said.

My son wasn’t faster than me, as it turned out. I met him at Market Square Jewelers, which was still open (after the RMV fiasco, we’d called ahead). He was trying out necklaces and rings. His favorite was too big on his biggest finger, although he tried to convince me it wouldn’t fall off. I think he was trying to convince himself. But with the gentle advice of the sympathetic woman behind the counter, he decided not to get it or anything else.

“You must be so disappointed,” I said on our walk back to the car.

It’s what I should have said before. With his head down, my son nodded, telling me he’d wanted to take the driving test today so he had a way to escape—to drive away for a few hours on his own.

But you can’t go to any public places now like the mall, I said.

He knew that—of course, Mom—but he could still drive someplace to take a hike, to be by himself. He’d go anywhere at all, my son said, and that would be okay. It would be okay.

If only I could hold him close, I thought then, as I did when he was little, rocking him with my body. Yes, it will be okay, brave boy.

• • •

Grief is a brick.

Grief is a brick I’d like to throw though my windows, breaking glass to shards, cutting shards. Make me bleed, Grief, go on.

Grief is the lichen on an ancient brick I pulled from this foundation, the grouting loose and cracking, so friable—a word I never use—friable lichen. I hate grief. I don’t want grief, but it’s there, sitting on the sidewalk, tossed through a stupidly, foolishly left-open door—not a window that would smash with a bang, just a brick with one corner knocked off.

Grief is friable, crumbling, disintegrating to dust. I think of smoke inside the edifice I built around myself, and now wisps are escaping from where I’ve pulled the bricks, they’re disintegrating, too, thinning in the air, already invisible.

But grief never disintegrates. Grief is a brick, burnt-black by city exhaust, much handled and used yet solid. Grief is a brick flecked with rings of lichen, gray rings of life and death, those rings on rings, years on years, falling away yet solid, a solid thing I don’t understand. But solid is a word I use, because that brick on the sidewalk, the one I tossed through an empty door, through every shadow, through smoke, will not go away. My grief is solid.

• • •

April 24, 2020

I haven’t been back to Harvard Square since that day in mid-March. That day, we weren’t being advised yet to wear masks; we were supposed to save them for medical workers. I can no longer imagine clicking my phone for a casual photo, asking those unmasked guys to smile.

My son, who’s handy with a sewing machine, ended up sewing each of us a mask into which we’ve inserted filters cut from a vacuum cleaner bag. My mask is functional but uncomfortable, an unattractive mummy-swathing that makes me far too aware of the rasp of my own breath. Nobody close to me has died yet, but I’ve heard too many harrowing stories from Harvard Extension colleagues and students (they’re front-line workers, they’ve lost their jobs or family members, they’re sick themselves).

That day in March, Starbucks hadn’t yet closed its cafes, despite an article in Vice that blared “Starbucks Employees Are Begging the Company to Shut Down Stores Because of Coronavirus.” But by the end of the week, my son found out his Cambridge store was closing, after all, and he’d receive two-weeks' pay in compensation. (As it turned out, Starbucks paid him for thirty days, although as his store gears up to reopen, he’s opted to quit.)

The first time I donned my mask, I snapped a photo and sent it to friends, labeling it “Mask Chic.” In it, I look like Cousin It. My sunglasses are ridiculous, my face framed by fly-away hair. Several weeks on, my humor is fly-away, too.

Last Friday, the official notice came down that my son’s senior prom has been canceled. They better not reopen the school then, he told me heatedly, because we could still have prom—not in the War Memorial and Field House, which the City of Cambridge has commandeered “to shelter homeless neighbors during the COVID-19 public health emergency”—I know that Mom, but in the cafeteria. We could plan something nice.

This past Tuesday, Governor Baker did close all the schools in Massachusetts for the rest of the academic year. Not only prom but the graduation ceremony has been canceled. No matter what we’d been telling ourselves to prepare, I wasn’t ready when I clicked open the April 22 email announcement from Principal Smith of the high school. My eyes blurred with tears as phrases burned forth: “particularly difficult for seniors…Graduation ceremony…THE highlight of the year… I am saddened…significant loss for our community, especially the Class of 2020.”

I didn’t think grief could surprise me anymore. Pre-pandemic, I thought I’d already weathered some of my worst losses: both parents, their deaths a year apart, after I’d witnessed their deterioration for a decade. That grief had been like a low slide through years of my life I’ll never get back, years when my son was making his own shift from adorable boy to teenager.

But at least I’m a master of grief, I used to tell myself. I knew the sharp onslaught from nowhere and the slow uncoiling on a rainy day, when I thought it would never end. No, Martha, it will end or transform into something softer, sweeter—cue the dreamy flute music and meditation tapes—except now I shout back, Shut the fuck up. I am master of nothing.

By the time my son reached sixth grade, he was alternately furious with me for visiting my failing parents so often in California and huggy, even tearful, unable to come up with the right words. I was the one in charge of finding the right words—which at the time, I couldn’t find, either—and so he rebelled against any homework that involved reading or storytelling. Yet he’d loved Harry Potter, poring through every fat novel as we rode the MRT when we lived in Singapore. The Percy Jackson series by Rick Riordan had been an earlier favorite, with me reading the novels aloud at bedtime until he moved on to read them himself.

By the time my son reached sixth grade, he was alternately furious with me for visiting my failing parents so often in California and huggy, even tearful, unable to come up with the right words. I was the one in charge of finding the right words—which at the time, I couldn’t find, either—and so he rebelled against any homework that involved reading or storytelling. Yet he’d loved Harry Potter, poring through every fat novel as we rode the MRT when we lived in Singapore. The Percy Jackson series by Rick Riordan had been an earlier favorite, with me reading the novels aloud at bedtime until he moved on to read them himself.

Last night, as I sobbed into my husband’s nubbly sweater, I was grieving again for my earnest little nine-year-old—the son I’ll lose to his adult life regardless of a pandemic. I cried in a way I hadn’t for my parents, although I knew that loss had been unloosened, too.

“I would've cried like this anyway,” I told my husband, even if our son could go to his prom and graduation, even if he could blithely decide on a college where he’d move on campus in the fall. He’s making a college choice right now, saying he still wants to go to New York City, although he may have to take an enforced gap year with us before he gets there.

I’m not that sad, he insists. But I sense deeper feeling in his languor, the chaos of his room, his desire to lose himself in video games with his friends rather than any pitiful semblance of online homework, the breaks he takes by working on a hoop of embroidery with pink flowers and green thread-tufts of grass—my bright, creative, contrary, fashion-minded, amazing boy.

Yet I can only speak for my own sadness. I wanted to go through those senior-year rituals with him. As the master of grief, I’d assumed the rituals would get me past the ache of him leaving, and now I’ve lost those. I’m imagining too much for him and not enough of his own world, which is far more realistic and sophisticated than mine was at eighteen. I grieve for his lost chances, but that’s in retrospect, in remembering what going away to college meant to me.

The grief I feel for New York City itself also brings me to tears, the grim reality at odds with a mythic place that’s always nurtured dreams of escape. In a disturbing twist of memory, the Percy Jackson books have come back to me, with their homage to Greek mythology. I recall images of the Empire State Building being ravaged by titans and monsters. The Last Olympian, the final novel of the series, includes an apocalyptic battle in Manhattan against Kronos, the Lord of Time. As Percy, the teenage demigod, describes the lead up:

I was standing outside the United Nations, about a mile northeast of the Empire State Building. The Titan army had set up camp all around the UN complex…. All along First Avenue, giants sharpened their axes….

“I hate this place,” Kronos growled. “United Nations. As if mankind could ever unite. Remind me to tear down this building after we destroy Olympus.”

Dreams of escape don’t die, though, especially for a young man like my son. He's starting his own life regardless, and he'll take on New York City and adulthood as he finds it. I’m the master of nothing, but maybe that’s where grief finally lands us.

My grief is a brick, solid yet undefined, such a terrible lack of definition. Except there’s loosening at the edges, more like water than dust. Call my grief fluid, then, rising up like a giant wave, surrounding me with teenage demigods and lost time and the knights my four-year-old collected because he loved jousting, all of us swirling along on the tide, like breathing, and I’m crying. I’m also riding somewhere new, not knowing what I’ll find.

Publishing Information

- “Baker-Polito Administration Announces Emergency Actions to Address COVID-19,” press release, Mass.gov, March 15, 2020.

- “Starbucks Employees Are Begging the Company to Shut Down Stores Because of Coronavirus” by Emma Ockerman, Vice, March 18, 2020.

- “Starbucks Is Paying Workers for 30 days, Even If They Don’t Show up for Work Amid the Coronavirus Outbreak” by Kate Taylor, Business Insider, March 20, 2020.

- “Baker Orders Schools Stay Closed Through the End of the School Year” by James Vaznis and Bianca Vázquez Toness, Boston Globe, April 21, 2020.

- “War Memorial Temporary Emergency Shelter,” City of Cambridge, April 1, 2020.

- “4-22-20 CRLS Community Announcement,” email from Damon Smith, principal of Cambridge Rindge and Latin School, April 22, 2020.

- The Last Olympian by Rick Riordan (Hyperion Books, 2009).

Art Information

- “Just Let Us Through” © Sean Davis; Creative Commons license.

- “Outside Mr. Bartley's in Harvard Square (March 16, 2020)” © Martha Nichols; used by permission.

- “Tribute in Light 2011” © Wasabi Bob; Creative Commons license.

Martha Nichols is Editor in Chief of Talking Writing. She’s also a faculty instructor in the journalism program at the Harvard University Extension School. Her “First Person” column, about media and publishing trends, appears regularly in TW. She’s the editor of and a contributor to Into Sanity: Essays About Mental Health, Mental Illness, and Living in Between (Talking Writing Books, 2019).

Martha Nichols is Editor in Chief of Talking Writing. She’s also a faculty instructor in the journalism program at the Harvard University Extension School. Her “First Person” column, about media and publishing trends, appears regularly in TW. She’s the editor of and a contributor to Into Sanity: Essays About Mental Health, Mental Illness, and Living in Between (Talking Writing Books, 2019).