TW Review by David Biddle

The “Do I Love Them Yet?” Syndrome

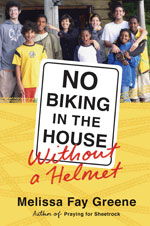

No Biking in the House Without a Helmet by Melissa Fay Greene, Sarah Crichton Books, 2011, 352 pp., hardcover.

No Biking in the House Without a Helmet by Melissa Fay Greene, Sarah Crichton Books, 2011, 352 pp., hardcover.

Once that last child begins to drive, most of us realize our capacity to parent is fading. We get a few years of empty-nest freedom before grandparenting kicks in. But the marathon is over. We finished!

Then there are the Melissa Fay Greenes of the world—and her attorney husband Don Samuel, a man who practices courtroom statements on his kids instead of reading them bedtime stories. Samuel and Greene, a journalist, had four children using their own DNA: Molly, Seth, Lee, and Lily. But then, in their early forties and with encouragement from their biological kids, the Greene-Samuel team adopted five more in less than a decade.

It began in 1999 with Chrissy (whom they renamed Jesse), a four-year-old boy of Romani ("gypsy") descent from a Bulgarian orphanage. Then they adopted five-year-old Helen from AIDS-ravaged Ethiopia, where, Greene notes, 11 percent of the nation’s children were orphans in 2001. After Helen came nine-year-old Fisseha (renamed Sol), followed by brothers Yosef (8) and Daniel (11)—also all from Ethiopia.

In No Biking in the House Without a Helmet, Greene tells the story of building this mega-family—two loving parents, two quirky dogs, nine amazing children from three different birth cultures—all living under one roof in Atlanta, Georgia.

Cute, huh? Sweet?

Hardly. Greene is not a master parent by any means—in far too many scenes, she just lets chaos reign in her household—and this is not a simple, feel-good treatise on the ultimate blended family. Her memoir is powerful and alluring, almost like a reality TV show where you actually care about the characters.

Greene comments intelligently on adoption, family, intercultural experience, and—above all—real love. This last resonates with me most, because as a mixed-race adoptee, I know that love between parents and children, adoptive or biological, is one of the greatest mysteries I’ve encountered in life.

Entering the Realm of the Unspoken

Too often, adoption stories are told from one point of view. It's an understandable limitation, given that so much of adoption's effect on everyone in a family is left beneath the surface. But probably because No Biking is about nine children with profoundly different points of view, it exposes the realm of the unspoken. When an author does that, the result is something very special.

Yes, there are many cute passages in this book. Greene is a great scene builder, and some anecdotes are almost pitch perfect. Here's little Helen’s first day in America:

Seth, Lee, and Jesse...led her down the driveway, lifted her onto the trampoline, bounced gently with her as she squealed, and then seated her in Seth’s lap on the forty-foot-high rope swing and pushed off. She had a high-pitched giggle, a little “eh-HEH” with the “heh” ending in a squeak, almost a gagging sound. The big kids mimicked the mouselike squeak, which made her squeak more. On the way into the house, six-year-old Jesse explained, “I Bulgarium. You Earth…you Earthy…you Earthyopium.

But such cheerful banter is in stark contrast to Greene's portrayal of the children's grim pre-adoption lives.

But such cheerful banter is in stark contrast to Greene's portrayal of the children's grim pre-adoption lives.

For instance, she notes that even at eleven years old, Daniel carried most of the emotional burden of what had happened to him and his "little lookalike brother" Yosef in Ethiopia. It is never clear how their mother, father, and younger siblings died. All Greene tells readers is that their uncle took them from their "round hut" in a mountain village to Addis Ababa, leaving them at the Big Atetegeb foster home run by Haregewoin Teferra.

Teferra is the central figure in Greene’s 2006 book There is No Me Without You, and Greene reports that her disciplinary methods could be harsh. In No Biking, she doesn't gloss over the trouble Ethiopian adoptees Sol, Daniel, and Yosef brought with them as they tried to adjust to their Atlanta household:

I believed the new boys had introduced the Silent Treatment into our family, because I knew Haregewoin had punished her children that way…. Excommunication shrinks a child’s spirit. It’s the punishment I most hate in the world, having experienced it as a child. I have never used it with my children, but now this soundless weapon was passed hand to hand eagerly among the boys.

Darkness, Darkness

As a journalist, Greene is an expert at handling political and cultural details. But No Biking goes beyond sympathetically portraying an orphan's life in his or her birth country. Greene's tale is provocative because it provides the unvarnished truth about struggling through the adoption process—then the post-adoption adjustment period—not just for the orphan who finally has a home but for the entire family.

Amid the more comic scenes, there's much darkness to be found in this story. Boys secretly watch pornography (racking up huge cable bills); adoptees face the crippling fear of loss and overwhelming homesickness; attachment disorder confuses everyone; mealtime behavior is often disturbing; and well-meaning parents battle to communicate with distraught newcomers who can’t speak English.

Greene’s account of the difficulties the family unwittingly found themselves in with Jesse is one of the most disturbing in the book. She was worried even when she first met the "snaggle-toothed" little boy in Bulgaria. At four, he was virtually wordless and filled with rage. He literally fought his way across the Atlantic on board a jet with his new family, then ran amok once they were home:

Greene’s account of the difficulties the family unwittingly found themselves in with Jesse is one of the most disturbing in the book. She was worried even when she first met the "snaggle-toothed" little boy in Bulgaria. At four, he was virtually wordless and filled with rage. He literally fought his way across the Atlantic on board a jet with his new family, then ran amok once they were home:

One afternoon, running through the den, Jesse fell and cracked his face against the sharp corner of the brick fireplace; it looked like a serious blow, but he wouldn’t let me examine it, and his dark bangs covered the point of impact. He didn’t even whimper. He bounced off the brick and ran on. That night as he slept, I peeled back his fringe of hair and was stunned by the deep and clotted gash I found.

Greene says that, after this discovery, she remembered everything she'd read about institutionalized kids learning not to cry or to respond to pain. She notes that Jesse had "other classic orphanage behaviors" as well: rocking himself to sleep, clawing at his skin, "plowing deep scratches till I restrained him."

Jesse’s developing story throughout this book is remarkable. So are the stories of all his siblings, adopted and biological. And then there are Greene's personal reflections. As she writes of Jesse at that time:

I was moved to pity for the child, as trapped and solitary in his own strange world as I was in mine, but I didn't know who he was. I had no idea if he was going to turn out to be a regular little kid or if we were at the top of a staircase that would descend into years of confusion and difficulty and loneliness and chaos.

Does Love Conquer All?

More than anything, this memoir provides an insightful discussion of adoption culture. Those who haven't adopted internationally may be surprised to learn there are special doctors who attempt to determine the risks of international adoption by watching video snippets of orphans around the world. They rely a great deal, it seems, on head circumference and what that says about brain development.

More than anything, this memoir provides an insightful discussion of adoption culture. Those who haven't adopted internationally may be surprised to learn there are special doctors who attempt to determine the risks of international adoption by watching video snippets of orphans around the world. They rely a great deal, it seems, on head circumference and what that says about brain development.

Greene describes taking the family on trips back to Africa to meet biological parents and relatives. She includes interviews with serial adopters and ponders the possibility of adoption addiction and child hoarding. When she discusses meeting a couple with 24 children, 8 of whom are their biological kids and many of whom have special needs, Greene wonders about the difference between a family and a group home.

She also gets to the root of big issues for adoptive parents. At one point, Greene describes managing her way through what she doesn’t yet understand is post-adoption depression:

It’s an awful thing we adoptive parents ask ourselves. Do I love her yet? Do I love him yet? Like the television ads for wireless phones: “Can you hear me now?” We don’t pursue this line of questioning about the children to whom we give birth. Yet here sat this little guy at the table, painstakingly peeling a hot dog, looking up with his sparkly eyes, and I asked myself, Do I love him yet?

This is one heck of an existential question. The birth of each of my three sons is among the most miraculous and transformative experiences of my life. Yet, when each came home from the hospital, I couldn’t help wondering: How differently did my parents feel when they brought home my little brother and sister (conceived by them) from when they brought me home at nine weeks old? I was with them for a trial period, and if it didn’t work out, well…they could always bring me back.

This book should be required reading for anyone contemplating adoption at any level. But in truth, No Biking in the House Without a Helmet should also be required reading for all young couples thinking about growing a family. Greene points to dozens of prickly child-rearing issues every parent has to face. She honestly illustrates how easy it is to make mistakes or to neglect reality when it comes to kids and large families.

She also makes it abundantly obvious that the most important traits parents bring to the game are creative love, humility, and humor.

Consider the book's title. In her description of the scene, Greene is sitting peacefully in the den when Sol rides through on a small bike he picked out of a neighbor’s trash. She pleads with him—"Don't make me say it. 'No biking in the house'"—but he keeps riding around with siblings draped over him. Finally, he plunges down the stairs to the basement, “bucking and shrieking,” and she can't help it:

You’re not wearing a helmet! Don’t ride your bike down the stairs without a helmet!

There is no question that Melissa Fay Greene is the anti-Tiger Mom.

Don't miss "Whoa! I'm a Character in a Friend's Memoir?," a companion piece about Melissa Fay Greene in this issue.

Art Information

- “Daniel and Yosef at Orphanage, date unknown” from Melissa Fay Greene’s website; used by permission

- “Jesse in Orphanage, 10/99″ from Melissa Fay Greene’s website; used by permission

- Melissa Fay Greene (detail) © Don Samuel; used by permission

David Biddle is a contributing writer at Talking Writing.

David Biddle is a contributing writer at Talking Writing.

David is now doing research for a book about Longtown, Ohio, a post-Civil War triracial settlement. He posts short fiction and blogs about literature, baseball, adoption, and the environment at The Formality of Occurrence.

This blog got its start as a free-form account of finding his birthmother in Indiana during a family vacation.