TW Opinion by Lorraine Berry and Martha Nichols

In 2014, How Much Clout Do Female Writers Have?

It’s as if the right words—women and power—have been airbrushed into an unthreatening mist. If you don’t define what you mean, nobody can criticize it. You won’t make mainstream publishers or other advertisers nervous. You’ll make the target audience (college-educated women, who buy the most books) feel good about themselves, burying key questions about who really has power.

Last Sunday, the New York Times Book Review published the print edition of “Women and Power” (October 12, 2014). It should have been something to celebrate—and the two of us were ready to pump our feminist fists. Just two years ago, the NYTBR was still fumbling all over the culture wars with an issue dubbed “A Woman’s Place.” Meant to be ironic, its cover review of Hanna Rosin’s The End of Men featured a cartoon of a huge red high heel stomping a tiny men’s dress shoe.

In contrast, the graphic design of the NYT’s latest women’s issue is text-driven, with three muted comics by Berlin-based illustrator Sophia Martineck. There are no hot-pink cartoons or high heels. The issue brims with writing by some of the best female critics around, including everything from reviews of Katha Pollitt’s Pro to Lena Dunham’s Not That Kind of Girl to Jenny Nordberg’s The Underground Girls of Kabul.

We wanted to love this—we really did. The individual reviewers here take on provocative books. Clara Jeffery’s review of Pollitt emphasizes that pro-abortion arguments need “to come out of the closet.” Kimberlé Crenshaw goes after Joan Biskupic’s book about Sonia Sotomayor (Breaking In) for its overly simplistic emphasis on race as the key to the Supreme Court justice’s success.

But as we read the issue last weekend, our initial excitement wore off. We both became increasingly angry—and worried—and confused. As Lorraine looked over the contents online, complete with retro-but-hipster flash animation, she thought: Doesn’t a section called "women and power" already tell me that we don't have any?

In the print edition, Martha couldn’t help noticing an arty full-page ad from Amazon for its Kindle Voyage. A young white woman with mussed dark hair gazes dreamily down at her Kindle, elbow cocked on a counter near a delicate cup and saucer. Behind her is a bar with gleaming glasses.

The confusion we felt is a tipoff. The NYT Book Review has brought together an array of female critics, even allowed them to say tough-minded things, yet sequestered them in a single issue that will soon be gone with the next news cycle. The overall impact is feminism defanged, in a way that makes the gender politics of power seem irrelevant when they are very far from that.

Decades ago, it was rare to see a noted literary institution, let alone the New York Times Book Review, devote an entire issue to women's writing. Even so, we two young rabble-rousers figured that by the then-distant future of 2014, we’d be past the need for “women’s issues.” We’d tell our kids about the days when you couldn't get people to take writing by women seriously (can you imagine?), and they’d laugh and say no way!, and think we’d been born in the Dark Ages.

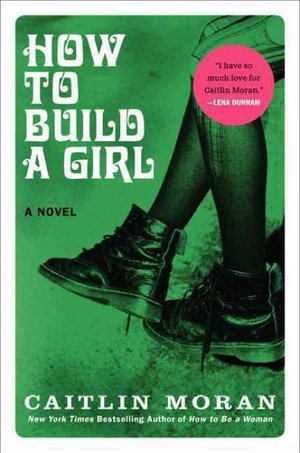

Now, we’re no longer dreaming of feminist nirvana. We know we should be grateful to have come this far, given the NYTBR’s historically lousy record of reviewing books by women or assigning female reviewers. In an email exchange yesterday with Caitlin Moran, in which we asked her what she thought of “cramming female writers into a special issue,” she notes that "a hundred and fifty years ago, we wouldn't have got reviewed in papers. In fifty years, we won't all be crammed together.”

Moran, whose novel How to Build a Girl is featured in the NYTBR issue, adds:

This is just the transition phase, where being a woman still isn't seen as being normal, so we all have to be herded into our weird little lady areas to keep us away from the ‘normal’ novels by men on subjects such as war and introspection and impotence and having affairs and worrying they haven't left a legacy.

Pamela Paul, formerly children’s book editor of the NYTBR, is now its top editor. She took over from Sam Tanenhaus in April 2013—six months after that big high heel stomped across the cover—and ever since, the number of female reviewers and books by women has marched upward. Yes, there’s been a change for the better at the premier book-reviewing outlet in the U.S. As Paul told Poets & Writers in 2013, "[M]aybe in two years I’ll be criticized for not having enough men in the Book Review! I think, you know, no matter what we do, we’re never going to please everyone."

When it comes to feminism, though, pleasing everyone is not the point. Sometimes even a humorous riff can get you in trouble, and trying to satisfy every reader with your coverage of hot buttons like abortion is doomed from the start. The NYTBR’s vagueness about what "Women and Power" means comes off as either an ecumenical shrug—Hey, everyone has a right to his or her opinion—or the kind of cluelessness that makes the New York book world seem like an insular club.

The only writer in the issue who gets a chance to nail the problem appears on the last page of the print edition. In Cheryl Strayed’s “Bookends” commentary for "Is This a Golden Age for Women Essayists?," she snaps right back, "Would we ever think to ask if this is a golden age for men essayists?" Strayed continues:

Is it even credible to use the phrase ‘men essayists’? Why does it sound incorrect in a way that ‘women essayists’ doesn’t? And why does a writer like me—female, feminist, familiar with the discreet and overt forms of sexism in the literary world and beyond—bristle when presented with such a query, one undoubtedly intended to celebrate rather than diminish the achievements of a category of people I admire and to which I belong?

Oh, how we wish this perspective had gotten the marquee treatment up front to frame the whole issue. But no. At a time when female critics from Moran to Mary Beard are being harassed all over the Internet, the NYTBR's lack of editorial attitude is especially troubling. The issue topic gets only one direct reference:

This week, the Book Review turns its full attention to women and power, a subject that brings to mind Woolf’s extended essay, 'A Room of One’s Own,' about the struggles of women writers.

In this "Open Book" note, John Williams focuses on the way Virginia Woolf’s stock rose in the NYT after an initially poor review of her first novel in 1920. Yet, almost a century later, the challenges facing female writers go far beyond a bad book review.

Just last week, the Atlantic published Catherine Buni and Soraya Chemaly”s "The Unsafety Net: How Social Media Turned Against Women,” which expands on current discussions about the harassment of female writers online. Lorraine recently interviewed Moran for an upcoming TW feature, and the two of them talked about how awful it is to have someone respond to your work not with civil disagreement—but by telling you that you need to be raped or murdered. Moran wonders if “people think I’m a computer robot, maybe? When I’m on Twitter? And therefore it’s okay to say you want to ram a sword up my cunt? But it’s not."

Among the many statistics cited in the Atlantic article, Buni and Chemaly point to a recent Demos study of more than two million tweets that indicates “female journalists” receive disproportionate amounts of social-media abuse. It’s even worse for writers of color. They quote legal analyst Imani Gandy, who notes wryly of her five years on Twitter: “Let’s just say that my ‘nigger cunt’ cup runneth over.”

Surely, this is about power. For whatever reason, women's writing provokes some men; it makes them feel powerless, and they take it out on women who write about feminist issues. Buni and Chemaly discuss, in disturbing detail, how much the Internet dream—that female and other minority writers would finally get a chance to express their opinions and have a voice in public discourse—has degenerated into a nightmare in which anonymous trolls can easily steal someone's private property, publish photos of a female writer’s naked body, issue death threats, or load GIFs into the comment boxes that reveal images of women being raped.

Almost any feminist publishing online or in print over the past decade has received such abuse—we both have at Salon, even at Talking Writing. And yet, the NYT’s “Women and Power” makes no mention of the way women who speak up are harassed, except in that oblique reference to “struggles” and Virginia Woolf.

No doubt the NYTBR will review the book about digital sexism (by Buni and Chemaly, we hope) when it’s in print a year or two from now. But the editorial myopia also extends to something more basic: economic power. In a world in which most writers and journalists are now grappling with the financial impact of online publishing, this NYTBR issue sidesteps money and class. If you were an anthropologist from Mars examining cultural documents like "Women and Power," you might well believe that most writers are middle-class, have been educated at private schools, and have enough disposable income to buy Kindles and sit at espresso bars.

Considering how long feminists have been fighting for equal pay and access, it’s a telling omission. Not all the reviewers in this issue come from privileged backgrounds; a few mention class, economic inequality, and race as forces that shape female lives. But the collective vibe, as with so many books slotted into the “women’s” category by publishers, is that money is best viewed through a personal lens.

We asked Moran how it’s possible to measure real power “if only the women of the upper classes have gained power?” Her email response:

All my indices are cultural—is seeing working-class women on TV normal? NOT JUST AS THE CLEANERS TO HIGH-POWERED SEXY LADY LAWYERS, BUT IN THEIR OWN SHOWS. When newspapers cover issues of poverty and the underclass, is the tone ‘them’—or ‘we’?

Even for those who have jumped class and gender hurdles to become high-tech executives, the “them” vs. “we” of money pops up—and it’s not just a personal problem. Last week, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella told a mostly female audience at the Grace Hopper Celebration of Women in Computing:

It’s not really about asking for the raise, but knowing and having faith that the system will actually give you the right raises as you go along…. That's good karma. It will come back.

These jaw-dropping remarks have received less press than the commentaries about social-media harassment, but “there were lots of murmurs in the crowd,” tweeted one attendee. Nadella, to his credit, backpedaled fast, tweeting that he’d been “inarticulate” and noting in an email to Microsoft employees the same day that “[w]ithout a doubt I wholeheartedly support programs at Microsoft and in the industry that bring more women into technology and close the pay gap.”

Progress? Perhaps. But when a distracted CEO lets slip something like this in a public forum, especially in the midst of exposés about how much harassment of women has been enabled by digital technology, it reveals what those in power really think.

You don't have to be rich to be powerful, and not everyone in New York who reads the Times makes six figures. Much as the two of us don’t like the cultural ghetto of special “women’s issues,” there could be good reasons for why those in charge at the 2014 New York Times Book Review think female writers need a room of their own. Do the editors believe affirmative action is still necessary? If so, fine. Say it. Did they put everyone together for practical reasons, because a whole lot of books by female writers have just been released? Also fine—tell us that.

The trouble is, they don’t say. It’s no good to imply that women have power, when you’re not even acknowledging your own economic privilege or the way you’ve smoothed the edges of a whole lot of Legitimately Angry Women. In an issue devoted to “Women and Power,” this failure to speak up, to explain, to take a stand feels like the exact opposite: voiceless, opaque, afraid.

Don't miss Lorraine Berry's TW Interview with Caitlin Moran in this issue. Their conversation touches on social-media harassment as well as male-vs.-female bylines and Moran's new novel How to Build a Girl (HarperCollins).

Publishing Information

- “Women and Power” issue: New York Times Sunday Book Review, October 12, 2014 (print). Reviews mentioned here:

• “Take Back the Right” (on Katha Pollitt’s Pro) by Clara Jeffery.

• “A Voice of a Generation” (on Lena Dunham’s Not That Kind of Girl) by Sloane Crosley.

• “Province of Men” (on Jenny Nordberg’s The Underground Girls of Kabul) by Rafia Zakaria.

• “In Her Judgment” (on Joan Biskupic’s Breaking In) by Kimberlé Crenshaw.

• “About a Girl” (on Caitlin Moran’s How to Build a Girl) by Ann Friedman.

• “Is This a Golden Age for Women Essayists?” (“Bookends” commentary) by Cheryl Strayed.

• “Worthwhile Woolf” (“Open Book” note) by John Williams.

- ‘A Woman’s Place’ in the NYT Book Review” by Lorraine Berry and Martha Nichols, Talking Writing, September/October 2012.

- “Q & A: Pamela Paul’s New Book Review” by Kevin Nance, Poets & Writers, July/August 2013.

- “The Unsafety Net: How Social Media Turned Against Women” by Catherine Buni and Soraya Chemaly, Atlantic, October 9, 2014.

- “Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella: Women Should Trust That ‘the System Will Give You the Right Raises’” by Colin Lecher, The Verge, October 9, 2014.

Art Information

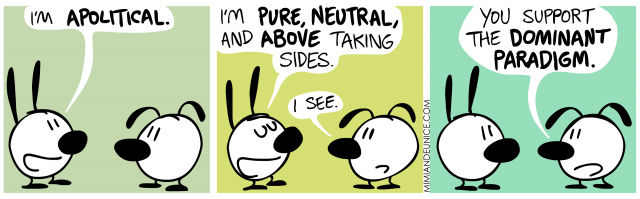

- “Apolitical” (Mimi & Eunice) by Nina Paley, July 27, 2012; Open Content license.

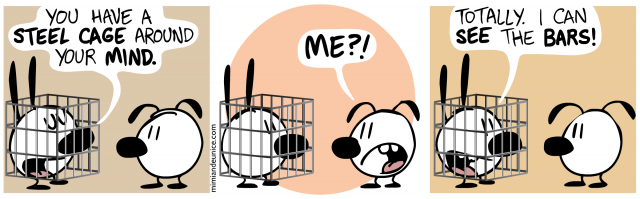

- “Steel Cage” (Mimi & Eunice) by Nina Paley, June 15, 2011; Open Content license.

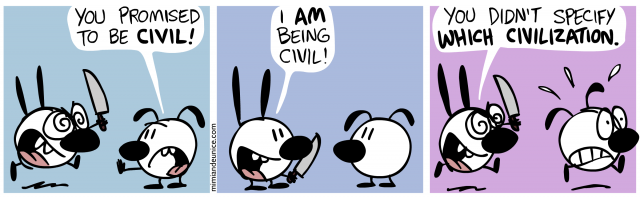

- “Civil” (Mimi & Eunice) by Nina Paley, July 10, 2012; Open Content license.

Lorraine Berry is TW's creative nonfiction editor and a writing instructor at the small New York college where she teaches that "creative nonfiction" does not mean you just get to make stuff up. When not teaching, she writes work that has appeared in Salon, Diagram, Dame, and Bitch magazine, among many other literary journals. Once upon a time, she was working on a doctorate in history, but left her program so that she could tell stories.

Lorraine Berry is TW's creative nonfiction editor and a writing instructor at the small New York college where she teaches that "creative nonfiction" does not mean you just get to make stuff up. When not teaching, she writes work that has appeared in Salon, Diagram, Dame, and Bitch magazine, among many other literary journals. Once upon a time, she was working on a doctorate in history, but left her program so that she could tell stories.

• • •

Martha Nichols is Editor in Chief of Talking Writing and a contributing editor at Women’s Review of Books.

For more about the place of female writers and their need for a feminist journal of their own, see Martha's 2013 WRB essay "A Profound Absence."