Theme Essay by Wendy Glaas

Why Most Manuscripts Don’t Click with Literary Agents

The summer I interned at a literary agency, it was all about Eat Pray Love. I couldn’t help remembering a scene from the 1992 movie The Player, when a writer pitching an idea to a Hollywood producer says, “It’s Out of Africa meets Pretty Woman!”

In 2010 at the Epstein Literary Agency, lines like “It’s Eat Pray Love but from the male perspective!” or “It’s Eat Pray Love but set in Provence!” wafted through each batch of query letters I sorted through. I’d chuckle, then feel a prickle of guilt. With a tap of the send button, writers were entrusting us with their babies. I knew I shouldn't be so glib.

In 2010 at the Epstein Literary Agency, lines like “It’s Eat Pray Love but from the male perspective!” or “It’s Eat Pray Love but set in Provence!” wafted through each batch of query letters I sorted through. I’d chuckle, then feel a prickle of guilt. With a tap of the send button, writers were entrusting us with their babies. I knew I shouldn't be so glib.

But after reading yet another “my story is unique” assertion in a pitch letter, I soon realized that very few memoirs are truly unique. My main job that summer was dealing with the slush pile of query letters—a pile that, in any given week, ranged from 150 to 225 queries.

I did take my sentinel duties seriously. At first, I imagined unearthing the next National Book Award winner or, at the very least, the next Twilight series. I’d find an unpolished gem for Kate Epstein, head of our agency. I’d make a name for my brilliant editorial and marketing instincts, for finding a fresh new narrative.

Unfortunately, it didn’t take long for me to discover that slush pile diving is far from glamorous. Instead, I found out how much difference a good pitch makes. Book authors now must be “players,” too, shaping their stories to fit target audiences.

With last year’s revelation in Writer’s Digest that Kathryn Stockett’s The Help was rejected by no less than 60 literary agents, it’s temping to say that all agents are cynical, overly focused on author “platforms,” and out of touch.

Some do leap on projects by Snooki or other celebrities. Sometimes writing quality and originality take a backseat. I learned about the platform concept immediately, because it was often Kate Epstein’s reason for rejecting an otherwise well-written pitch (“this would be hard to place without a substantial author platform”). It took some getting used to, especially if I’d enjoyed an author's sample chapters.

Yet, I also learned that agents aren’t simply making cynical platform decisions. Even small agencies like Kate’s are inundated by the river of junk that streams through their doors—and there's often very little that's new and different.

The process can seem brutal, but the best agents are effective gatekeepers. At the very least, they help writers tailor their lofty expectations.

“Dear Honorable and Respected Literary Agent”

I admire the chutzpah of anyone who sits down and writes a book. At the same time, as I dove through the agency’s slush pile, I was astonished that so many authors could finish the gargantuan task of writing, say, an entire trilogy, yet be unable to put together a compelling query letter.

That summer, I came across SlushPile Hell, a blog compiled by “one grumpy literary agent” out of “a sea of query fails.” I cackled at some of the more egregious examples, but I saw similar patterns myself. Here’s a recent excerpt (December 12, 2011) from SlushPile:

Dear Honorable and Respected Literary Agent / Patron. Hope this email finds you in mesmerizing happiness and prosperity. At the outset, a triumphant privilege to be writing to you. I am emailing you my entire Poetry Book which is 607 pages as an attachment.

In a couple of instances at Epstein, the authors didn’t even write the actual query letter (unless they were writing about themselves in the third person, a red flag for other reasons: David Blowhard is the best young novelist of his generation—nay, a thousand generations.) This made it tough to gauge personal writing style.

Other authors didn’t include sample material. In one case, a writer attached printed clips from a newspaper, and Kate correctly noted that she couldn’t tell how much of that person’s authentic voice remained after an editor had worked on the piece.

One author suggested that his book would no doubt be made into a movie and that Brad Pitt would be a good choice to play him. (This person could generously be called “tenacious,” as he sent the same pitch letter every few weeks.)

And very few authors seemed to understand the difference between capitalizing on a trend and an eye-glazingly derivative idea.

“Not Unique Enough”

Even when writers sent perfectly polite, non-pressuring letters, I found that they often hadn't researched Epstein's areas of interest. When Kate worked in acquisitions at a Boston-area book publisher, practical nonfiction was her bailiwick; books in this genre were more likely to get her attention, as she had more contacts in this area.

In the summer of 2010, she focused on nonfiction—including practical how-to’s and memoir—and young adult (YA) fiction. If the latter were written well, I generally passed these on to Kate. Yet, the slush pile kept ferrying in vampires, werewolves, and teenage magicians (and sometimes all three). Occasionally, there would be a dystopic-themed pitch that riffed on The Hunger Games.

In the summer of 2010, she focused on nonfiction—including practical how-to’s and memoir—and young adult (YA) fiction. If the latter were written well, I generally passed these on to Kate. Yet, the slush pile kept ferrying in vampires, werewolves, and teenage magicians (and sometimes all three). Occasionally, there would be a dystopic-themed pitch that riffed on The Hunger Games.

I learned several shorthand labels from Kate, including “not unique enough.” For example, I fielded many query letters about learning disabilities, substance abuse, and depression or other forms of mental illness. (Kate recently asked via Twitter whether the spate of abuse survivor memoirs is due to the success of The Glass Castle.)

On the other hand, memoirs that focused on less common ground, such as losing a child, were "too niche-y."

Other pitches suffered from being “not timely enough.” Kate considered a memoir about Vietnam, for example, too dated. (Chances are an agent or two felt similarly about The Help, which takes place during the Civil Rights era.)

Every week, Kate did ask a handful of writers for more sample pages—only to change her mind after receiving them. Most of her feedback had to do with inconsistent voice, lack of a single point-of-view character, or a book that simply required too much work to take on.

In the case of a young woman's 100,000-word memoir, Kate suggested that she trim it down by almost half—a colossal editing task. But as Kate told me, "Only someone like Bill Clinton can get away with a 100,000-word memoir."

“Heck, No!”

I'm all for a man's reach exceeding his grasp, but with apologies to Robert Browning, he did not manage a slush pile. So many times, I found myself thinking, “This would be great as a magazine article. And it’s a lot more likely to get published in a magazine.”

At this level, gatekeeping by agents makes sense. Marketability often coincides with a new idea or voice, and there has to be some way to cull the herd. In the end, though, I saw that an agent’s decisions are also subjective and often arbitrary.

At this level, gatekeeping by agents makes sense. Marketability often coincides with a new idea or voice, and there has to be some way to cull the herd. In the end, though, I saw that an agent’s decisions are also subjective and often arbitrary.

On her agency website, Kate Epstein refers to her “personal tics” as a guide in choosing material. While I tried to focus on queries that meshed with her interests, I’d occasionally read something that grabbed me, and I’d pass it along.

Sometimes she'd agree that it was worth asking the author for his or her manuscript. More often than not, though, she’d veto my selections, even if it was something I thought had commercial viability.

I realized during the process that I had my own tics, too. I can hear Kate’s shorthand assessments as I list them here: a how-to book by a longtime hairstylist on dealing with unruly, curly hair (“Curly Girl is already on the market”); books about Alzheimer’s (“overdone”); a biography of the scientist behind a famous twentieth-century hoax, written by his son (“too esoteric”).

Maybe it’s the tics of each agent that guarantee an infinite hum of manuscripts and query letters. My grandmother used to say “every pot finds its cover” when talking about love and marriage, and maybe finding the right agent is a similar process. I sometimes wonder about the people behind the letters I’ve mentioned. Did the Eat Pray Love folks find that elusive agent who wanted to deal exclusively with memoirs set in Provence or written from the male perspective? Or did they give up and self-publish?

I can’t speak specifically to The Help and what Kathryn Stockett may have missed in her first 60 query letters, especially since she refined her work in response to feedback. At the very least, I respect her tenacity. Rejection is a large part of the dance.

But after seeing the process firsthand, the efforts all these writers put into finding an agent seemed to add up to a crap shoot. It still amazes me that a particular manuscript winds up on the right agent’s desk at the right time and is unlike anything else out there.

When I talk to people about my interest in book publishing, they usually ask if I’m working on a book myself. “Heck, no!” is my knee-jerk response. Going through a slush pile was a humbling antidote to such aspirations.

“Every Pot Finds Its Cover”

And yet, things often do click. Each time I enjoy a book, deeply satisfied that a particular author’s writing has made it to the marketplace, I know the process works. It's reassuring to see that sometimes it is about the writing.

I recently spoke with Kate about Silver Like Dust, a memoir by Kimi Cunningham Grant that she’d successfully sold to Pegasus Books after my time at the agency. I'd become so used to Kate's polite rejection emails that to hear her gush about a book made me realize how much she'd been smitten.

"It was magnificent, and I wanted it bad," she says of the manuscript.

Silver Like Dust is the story of Grant’s Japanese grandmother, who spent five years at a U.S. internment camp during World War II. Ironically, Kate told me that Grant almost didn't send her query to Epstein, given Kate's public stance against "grandma stories."

But what sold Kate was the trifecta of writing ("fantastic"), marketability (strong appeal to a female audience), and uniqueness (a part of history that isn't often discussed).

It’s also likely that Grant’s memoir touched on Kate’s personal interests and concerns, because representing it gave her, as she says, "a sense of contributing to justice if I helped Kimi find a publisher."

Silver Like Dust has just been released. The pot did find its cover! So even if the endless rejection minuet continues to daunt me, I know that a single advocate who loves a story and is prepared to fight for it can turn everything around.

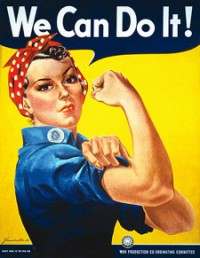

After my summer with the slush pile, it’s clear that many of my own book ideas were niche-y or overdone. But now, on my most hopeful days, I'm also a literary Rosie the Riveter, sleeves rolled up to tackle a laptop instead of machinery, singing out, "Heck, yes!"

Publishing Information

“60 Rejection Letters Didn’t Stop Kathryn Stockett and Her Bestseller ‘The Help’” by Brian A. Klems, Writer’s Digest, August 16, 2011.

“60 Rejection Letters Didn’t Stop Kathryn Stockett and Her Bestseller ‘The Help’” by Brian A. Klems, Writer’s Digest, August 16, 2011.- “Dear Honorable and Respected Literary Agent…,” SlushPile Hell, December 12, 2011. (Grumpy commentary on this query: “Obviously I’m in mesmerizing happiness and prosperity. I’m a literary agent. Duh.”)

- Kate Epstein’s website: The Epstein Literary Agency.

- Silver Like Dust: One Family's Story of America's Japanese Internment by Kimi Cunningham Grant (Pegasus Books, 2012).

Art Information

- “Waste Basket” © Zsuzsanna Kilian; stock photo

- “Waste Paper” © Christophe Libert; stock photo

- “Trash Can Paper” © Steven Depolo; Creative Commons license

- “We Can Do It!” poster by J. Howard Miller of Westinghouse, 1942, commissioned by the War Production Co-ordinating Committee; public domain (Note: According to the National Register of Historic Places listing on Wikimedia Commons, the poster depicts worker Geraldine Doyle, although it’s closely associated with Rosie the Riveter; the original resides in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.)

Wendy Glaas is an assistant editor at Talking Writing and clerk of the TW Advisory Board.

Wendy Glaas is an assistant editor at Talking Writing and clerk of the TW Advisory Board.

She's never read Eat Pray Love (nor seen the movie) and probably never will. Her own YA tastes were more Judy Blume than Stephenie Meyer, but it's always good to see what the kids are reading these days. She raises a glass to everyone searching for the right gatekeeper in 2012 and hopes that they get the name right when sending an email. (Please.)

"It’s not so bad that I’ve got piles of books dotting the floor. But now piles have sprouted on my nightstand, radiator covers, and coffee table as well. I admit it: I’m a bookstore junkie." — "My Name is Wendy, and I'm a Bookstore Junkie"