TW Column by Emily Toth

Can You Teach Wit, Intuition, and Flair?

You can learn a lot when you share a bullpen office.

In my very first teaching job, one of my six office mates was “Herr K.,” a mysterious Eastern European. He was dapper and angsty. His students were just angsty—like the one who came in one day and asked, “Can you teach me to have intuition?”

Herr K. roared with rage. “You are an utter nincompoop! You are either born with intuition or you have it not ever!” A vein was throbbing in his temple. We were sure he would have a conniption fit.

Herr K. roared with rage. “You are an utter nincompoop! You are either born with intuition or you have it not ever!” A vein was throbbing in his temple. We were sure he would have a conniption fit.

He didn’t, but that’s one of my first memories of an impossible question. Another is, “Can you teach creative writing?”

You can certainly teach writing (grab a stylus or a pencil), but can you teach creativity? Doesn’t it involve some kind of intuition? Some flair, some muse?

Well, there are some easy tricks that anyone can learn. I teach them in all my nonfiction writing classes:

-

From Anne Lamott, Bird by Bird: Get over the blank page jitters by telling yourself to write “a shitty first draft.”

-

From Stephen King, On Writing: Never use adverbs.“The adverb is not your friend.” The adverb was created “with the timid writer in mind.”

-

From William Zinsser, On Writing Well: Cut out clutter and simplify. “Prune and strive for order.”

Whereupon any well-socialized student will cry “Ernest Hemingway!” to point to the ultimate pruner. Consider his description of the character Frances in The Sun Also Rises:

She was tall and had a smile.

Many literary critics praise such writing. What brevity! What compression of a deep well of feeling into a few pointed words! What wit!

“What shit!” said one of my sophomores. “It’s boring and simpleminded, like a first grader.”

With which I have to agree. There’s simple and there’s simpleminded. When I saw the predictable poseur Hemingway in Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris, I laughed my socks off.

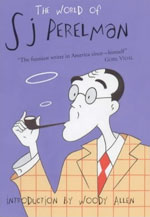

A good piece of writing has to surprise you, and much of Woody Allen’s comedy comes from the snapper surprise he learned from S. J. Perelman. It’s a list of three things, two profound and one silly, like this: “We thirsted for righteousness. We yearned for social justice. We’d sell our kidneys for a really good knish.”

“Knish,” a superbly comic word, was F. Scott Fitzgerald’s favorite when he shlepped around to Jewish delicatessens just to revel in the sounds. He also loved “gefilte fish,” “kugel,” and “blintzes.”

As Zinsser points out, wit comes through the ear as well as the eye. And so I exhort my students to read their writing aloud—especially the last words of each paragraph.

The liveliest, best-paced writing ends each paragraph with a snapper. My novelist friend Laura Joh Rowland looks at the final words of paragraphs when she’s deciding whether to buy a new book. No snapper, no sale.

But once you know that you need a snapper, can you just reel one in—the way you shun adverbs, obliterate clutter, and accept that you may have a shitty first draft?

But once you know that you need a snapper, can you just reel one in—the way you shun adverbs, obliterate clutter, and accept that you may have a shitty first draft?

Some writers seem to produce snappers effortlessly. Dorothy Parker was one whose wit “was so wonderful that neither age nor illness ever dried up the spring from which it came fresh each day,” wrote Lillian Hellman, who mostly hated everyone. Lord Byron’s lusty wit in Don Juan was deplored, especially the line announcing that the racy parts in poetry were relegated to an appendix, “which saves in fact the trouble of an index.”

Many “serious, literary” writers can’t do snappers. Their minds don’t see the incongruity or hear the peculiarity, and they’re reluctant to show off. Asked their favorite cities, they’ll probably say Rome, Paris, and London—instead of “Rome! Paris! Sheboygan!” (for its sound) or “Rome! Paris! Dorking-on-Thistle!” (for its absurdity).

I don’t think you can teach a flair for words or an ear for the ridiculous. There’s also an audacity in the best writers. I’m still wowed by Nora Ephron’s conclusion to her 1975 essay, “A Few Words about Breasts,” a lament about being flat-chested in a mammary-fixated world.

Many have told her that breast size doesn’t matter, Ephron writes. Her almost mother-in-law advises her to be on top, so he won’t notice. Others say that people should love you for your qualities of personality, which are the eternal verities that matter. Ephron says:

I have thought about their remarks, tried to put myself in their place, considered their point of view. I think they are full of shit.

Is she retro, or archaic, or one of the best snapper-writers in the history of the universe?

You shouldn’t have trouble deciding, not ever.

Unless you’re an utter nincompoop.

Publishing Information

- Nora Ephron, Crazy Salad: Some Things About Women (Knopf, 1975).

- George Gordon, Lord Byron, Don Juan (1819).

- Lillian Hellman, An Unfinished Woman (Little, Brown, 1969).

- Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises (Scribner, 1926).

- Stephen King, On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft (Scribner, 2000).

- Anne Lamott, Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life (Pantheon Books, 1994).

- William Zinsser, On Writing Well (HarperCollins, 1976).

Emily Toth, professor of English and Women’s Studies at Louisiana State University, is a contributing writer at Talking Writing.

Emily Toth, professor of English and Women’s Studies at Louisiana State University, is a contributing writer at Talking Writing.She is the author of eleven published books, including biographies of Kate Chopin and Grace Metalious, and two advice books: (Ms. Mentor’s Impeccable Advice for Women in Academia and Ms. Mentor’s New and Ever More Impeccable Advice for Women and Men in Academia). She writes the Ms. Mentor online advice column for the Chronicle of Higher Education.