Memoir by Carolee Bertisch

Excavating a Father’s Possessions

As I open each envelope, the ancient rubber bands holding it together fall into little worms at my feet.

Rubber bands and envelopes were only two of the possessions my father collected. Cleaning out his condominium a month after his death, I unearth bank and brokerage account statements going back to the 1970s; telephone bills; nail clippers; newspaper articles from his days as Republican Party chairman; even a Christmas card from George and Barbara Bush and an old Bush family picture with W clowning!

Harry never threw anything away. Plaques and certificates from the Elks, the Masons, the Anti-Defamation League, and his synagogues adorn the walls. There are brightly colored yarmulkes from every wedding, bar mitzvah, and other celebration he attended. And prayer books.

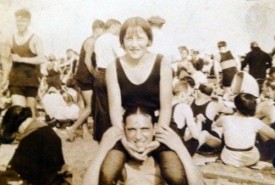

Scrapbooks of pictures take me on a journey through my childhood, as I try to put names to the faded, sepia-toned faces. One of my earliest memories is learning to swim, that sensation of floating on top of the water for the first time. I find a picture of me in a pond on Aunt Sarah’s farm. And pictures of my parents, young and beautiful, at the beach in old-fashioned striped bathing suits, arms twined around each other.

Scrapbooks of pictures take me on a journey through my childhood, as I try to put names to the faded, sepia-toned faces. One of my earliest memories is learning to swim, that sensation of floating on top of the water for the first time. I find a picture of me in a pond on Aunt Sarah’s farm. And pictures of my parents, young and beautiful, at the beach in old-fashioned striped bathing suits, arms twined around each other.

Although my mother died almost eleven years ago, her name remains on stock certificates and checkbooks.

I throw away stacks of unused checkbooks from banks no longer in existence. There are stock certificates from bankrupt companies, including the Trump Taj Mahal in Atlantic City, and all the correspondence that accompanied them.

Two wallets are crammed with special cards from the Crystal Palace and other casinos in the Bahamas, where Dad gambled regularly at the craps tables—standing for ten hours at a time—before he broke his hip at the age of 95. A cabinet in the den overflows with stacks of used casino playing cards, holes punched in the middle.

One mystery is solved. At my parents’ fiftieth anniversary party, I asked if any pictures existed from their wedding. Who were their attendants? No answers or evidence. So, I concluded, my brother and I must have been illegitimate. We laughed about it. But to my surprise, I find their marriage certificate, dated January 14, 1928, in one of the envelopes, along with my mother’s citizenship papers.

My brother died in 1987, but my father kept the signed agreement for $750 he had lent my brother years before his death, as well as letters and notes from loans to others. Two humidors are filled with cigars that he chewed and puffed until the day he went into the hospital at the age of 97. The Power of Attorney agreement that he could never find to give me is in a large envelope, along with his last will and testament and a Trusted Third Party amendment.

I tally up statements from ten different bank accounts and two brokerage accounts and search through his clothes for the cache of hundred-dollar bills he always kept. The cash, which had always resided in the pocket of his pink suit, is gone, probably taken by the last of the 33 women who cared for him after he broke his hip three years before he died. He fired most of them, his temper flaring when they dared to tell him what to do. Others left because he wanted them to get cozy and lie down next to him in bed.

My daughter-in-law, Jennifer, and I don’t bother counting his shirts, but there are hundreds, some with the tags still on them. Ten large black bags of clothing, including three tuxedos, go to a charity, B’nai B’rith. We can picture kids who loved vintage clothing trying on his wildly patterned polyester shirts and red and black plaid trousers.

My daughter-in-law, Jennifer, and I don’t bother counting his shirts, but there are hundreds, some with the tags still on them. Ten large black bags of clothing, including three tuxedos, go to a charity, B’nai B’rith. We can picture kids who loved vintage clothing trying on his wildly patterned polyester shirts and red and black plaid trousers.

He’d saved the bill of sale from his final beloved Lincoln Town Car, which he’d had to sell when the Florida Department of Motor Vehicles called him in for an eye test at the age of 90. Harry almost convinced the man at the Department that he could still see, forcing him to take my father around to three different machines.

The family knew he had macular degeneration and could not possibly pass the test. We cheered when the state forbade him to drive, something we’d pressed for without success.

He always said, “I can see; I just can’t read.” There was no way to know how much he saw because he always looked straight into your eyes, as if he could see. But his signature was a tiny slanted squiggle, after he was shown where to place the pen. His favorite place to watch TV was in the kitchen, two feet from the screen, puffing his cigar.

It’s true that Harry was a child of the Depression, born in 1908, but did that make him into the inveterate collector of objects and paper that he was?

As the youngest of five children and the only one to live beyond 72, he was the last remaining member of his generation, outliving friends and family. Although he retired in 1973, he had accumulated more money 33 years later than he’d had at retirement, one of his proudest accomplishments and one that he reiterated often.

Now I have filled a large blue accordion folder with the papers I need to settle his estate, carefully labeled. Harry Ackerson’s life ended in envelopes, white and yellow and brown, small and large, bound tightly with rubber bands, now departed.

Art Information

- “Carolee’s Parents at the Beach” and “Carolee and Aunt Sarah at the Farm” © Carolee Bertisch; used by permission

Former English facilitator and writing coordinator for the Rye Neck School District in Westchester County, New York, Carolee Ackerson Bertisch is the author of Who Waves the Baton?, a book of poetry and prose.

Former English facilitator and writing coordinator for the Rye Neck School District in Westchester County, New York, Carolee Ackerson Bertisch is the author of Who Waves the Baton?, a book of poetry and prose.

Bertisch has been published recently in the anthology Word Trips and the online zines The Infinite Writer, Old City Cool, and deadpaper. Her poem, "Common Ground," won First Prize in the North Florida Writers’ Festival.