Theme Essay by Jeremiah Horrigan

Food Writing? Who Cares? Let’s Talk About Hot Dogs

I came to Raymond Sokolov’s door with trepidation. The distinguished restaurant critic and columnist has spent his life writing about food. I’ve done little more in my writing career than eat it.

I don’t know the difference between a gourmet and a gourmand. Until fairly recently, I thought chateaubriand came in a bottle. The “fancy foods” of my childhood ran the gamut from over-cooked Sunday ham festooned with charred pineapple rings at Easter to walnut-packed cheddar cheese balls at Christmas.

If he’d wanted to, the 70-year-old Sokolov could easily have made mincemeat of my culinary illiteracy when I interviewed him for this issue of TW. But instead, to my great relief, we didn’t speak of cuisines old or nouvelle but rather about one of the few food items I’m deeply familiar with: the hot dog.

Sokolov began his career as a foreign correspondent at Newsweek in 1965. He later worked the arts beat there until ‘73, when he succeeded Craig Claiborne as restaurant critic and food editor of the New York Times.

His interests as a restaurant critic were wide-ranging; not only did the entrées get the once-over, Sokolov paid acute attention to a restaurant’s lore, its décor, even its politics. After leaving the Times in the mid-1970s, Sokolov worked for almost twenty years at the Wall Street Journal, where he was a founding editor of the daily Leisure and Arts page. In 1980, he also began a twenty-year stint as a freelance columnist for Natural History magazine, where he wrote about what he calls “America’s foodways.”

This October, I visited Sokolov in his home in Gardiner, a tiny town about 90 miles north of Manhattan and a place where some of the country’s earliest settlers, French Huguenots, built their homes of stone more than three centuries ago. Sokolov and his wife Johanna Hecht, a retired curator of European art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, live in one such example of American architectural austerity.

But inside, there’s no stoniness. Sokolov made me feel welcome in his softly lit living room, where I immediately sank into a comfortable couch. Within seconds, Duncan, the couple’s very friendly Kromfohrländer dog, put his muzzle in my lap and fell asleep.

I’d originally become interested in Sokolov when I heard about Wayward Reporter, his 1980 biography of the great New Yorker writer A. J. Liebling. In the ‘40s and ‘50s, this undefeated heavyweight champ of American press criticism was also a heavyweight in the then-nascent realm of postwar food writing. Here’s Liebling in his 1959 book Between Meals: An Appetite for Paris:

The primary requisite for writing well about food is a good appetite. Without this, it is impossible to accumulate, within the allotted span, enough experience of eating to have anything worth setting down. Each day brings only two opportunities for field work, and they are not to be wasted minimizing the intake of cholesterol.

Alas, Sokolov and I never got around to discussing Liebling. The current state of food writing didn’t get much of an airing, either.

“I’m probably not competent to discuss that,” he told me.

“C’mon!”

“The world that I came out of was print, magazine, mainstream journalism,” he said. “I almost never worked for the food press per se.”

“O-kayyy....”

Sokolov took a deep breath. He cast his eyes at the ceiling, as a teacher might when confronted with a particularly dim student.

Then he made clear that the world of food writing has changed. Irrevocably. He recalled talking with a colleague 25 years ago about how he no longer enjoyed the clout of his predecessors at the New York Times like Claiborne. Even then, they were mourning the fact that a newspaper critic could no longer make or break a restaurant with one review.

Then he made clear that the world of food writing has changed. Irrevocably. He recalled talking with a colleague 25 years ago about how he no longer enjoyed the clout of his predecessors at the New York Times like Claiborne. Even then, they were mourning the fact that a newspaper critic could no longer make or break a restaurant with one review.

Now it’s impossible to keep up with all the new outlets for reviewing restaurants and writing about food—or as he called it, “the whole world of food blogs and forums and aggregating sites and things like Yelp.” That’s where the clout is today.

Sokolov sighed again, passing a hand through his still-thick white hair, as if trying to comb out his exasperation.

We’d found our common ground. In a televised world brimming with Iron Chefs and boiling over with far too much Rachael Ray, I was gratified to see that for Raymond Sokolov there were so many tastier things to talk about.

Once he began discussing the fanciful and bizarre histories of American regional specialties, the focus of his Natural History column, Sokolov became more cheerful. Speaking in a deliberate, mellifluous voice made for radio, he recalled the way his search for forgotten or underground specialties—including the perfect hot dog—sent him to parts of the country most national journalists never visit, let alone write about.

Beyond his hometown of Detroit, he’s visited such glamorous culinary outposts as Duluth, Minnesota, and Peoria, Illinois.

It was never a matter of calling ahead for reservations or of knowing the maître’d.

“There was this place in Boston,” he told me. “This famous place run by a very old black man who’d figured out a way of charbroiling a hot dog that was fabulous.”

Only trouble was, this “place” was a moveable feast—a van resembling an ice cream truck. It could usually be found parked in an empty lot outside a worn-out string of meatpacking warehouses in Roxbury—but not always. In order to write about the man (a former DJ who went by the name of “Speed”) for the Wall Street Journal, Sokolov had to track down the van where he practiced his magic.

Both in that 2008 Journal article and in his conversation with me, Sokolov declared Speed’s all-beef dog, marinated in apple cider and brown sugar, to be the finest in the land.

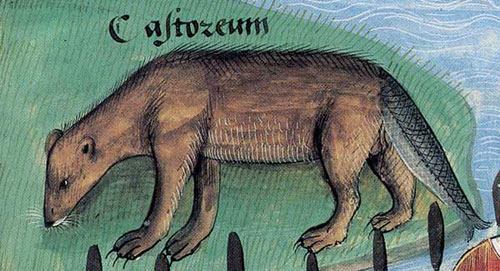

He also described a visit to Toledo, Ohio, where the legendary swamp rabbit waddled into his life. It was then that I got a taste for how strange American cuisine can be and for Sokolov’s pleasure in recounting such discoveries. He served up his story of the swamp rabbit, better known among non-Toledoans as muskrat, with great relish.

He also described a visit to Toledo, Ohio, where the legendary swamp rabbit waddled into his life. It was then that I got a taste for how strange American cuisine can be and for Sokolov’s pleasure in recounting such discoveries. He served up his story of the swamp rabbit, better known among non-Toledoans as muskrat, with great relish.

It seems that during the Depression, the Catholic bishop of Toledo (although some say it was the bishop of Detroit) declared that on Fridays—a day on which Catholics were forbidden to eat meat—the faithful could eat muskrat.

The rationale? This giant rat lived part-time in water. Swamp water. Still, the creature’s lack of fishly accoutrements was something hungry Toledoans were evidently willing to overlook. Sokolov gleefully reported that while the ecclesiastical dispensation has long since become moot, the taste for this furry pseudo-fish has persisted on local palates and menus, where you might still find its tender, gamey flesh described as “swamp rabbit.”

His tale reminded me of a 1980 Wall Street Journal story I revere by reporter Gay Sands Miller, a hilarious account of government efforts to rename—for obvious reasons—such perfectly delectable fish as the mudblower, grunt, and ratfish.

“Of course, of course,” Sokolov laughed. “It’s nothing new, really. The major meats all have these names that are actually French. We don’t say ‘cow’ and ‘steer’ or ‘calf,’ we say ‘beef’ or ‘veal.’"

He shrugged. C’est la vie.

Before lifting Duncan’s head from my lap and saying goodnight, I asked one final question: What is the state of American food—not just food writing—these days?

“Oh!” Sokolov threw his arms out in an embracing gesture. “This is a paradise!”

He leaned forward from his perch on the couch, suddenly intent. Didn’t I think that the local dining opportunities were amazing? That the quality of food—even in supermarkets—was more diverse and interesting than ever before?

I had to agree. At last count, in the upstate New York college town of New Paltz where I live, just down the road from Sokolov and Hecht’s home, there are more than sixty restaurants, trattorias, pubs, taco joints, pizzerias, vegan outposts, and three—count ‘em—sushi bars. Main Street’s mom-and-pop deli sells ostrich steaks and ground bison; the Stop ‘n’ Shop mega-store is awash in fat- and gluten- and nut-free exotica.

And that’s not all, I thought while driving home. Only thirty minutes away, in Poughkeepsie, a city at least as far off the beaten culinary path as Duluth or Peoria, I had recently discovered a restaurant called Soul Dog. They serve a hot dog to die for, slathered with peanut sauce and slivered cucumbers.

A paradise, indeed.

It made me wish Soul Dog kept later hours. I would have enjoyed taking Raymond Sokolov there that evening. And it left me eager to read more of his dispatches from the table, which I now know are as notable for their grace and wit as any essay by the great Liebling.

A Taste of Raymond Sokolov

Selected Books

- The Saucier’s Apprentice: A Modern Guide to Classic French Sauces for the Home (Knopf, 1976).

- Wayward Reporter: The Life of A.J. Liebling (Harper & Row, 1980).

- Why We Eat What We Eat: How Columbus Changed the Way the World Eats (Simon & Schuster, 1991).

- How to Cook: An Easy and Imaginative Guide for the Beginner (revised edition, William Morrow, 2004).

Down the oblate, winding stair, past the whiskered hag concierge, and around the corner, they were waiting for me: a family of Basques with a cheap menu. Tournedos bordelaise could be had, ‘bleeding,’ as I learned to say, for the equivalent of $1.50.

That night I knew enough to know that I had ordered some kind of steak. From bordelaise, I knew not.

I was, however, aware that the French distinguished their food with ‘sauces,’ but it was not until the little barded tournedos was brought, aswim in a lush and velvet medium, that I began to understand what had been meant by those groans of retrospective pleasure which the racy dowager next door to us in Detroit had emitted involuntarily as she regaled us with lengthy accounts of her unstinted banquets in Michelin's three-starred temples.

‘Oh, the sauces!’

And oh, that bordelaise of my first night in France. I am certain, now, that it must have been third-rate: padded with tomato, unskimmed and murky, chalky with raw flour. But I remember a taste of extreme purity, an excitement that, along with the thrill of mainlining the French language, held me captive in Paris for the next two months....

—from the introduction to The Saucier's Apprentice, Raymond Sokolov

Publishing Information

- Between Meals: An Appetite for Paris by A.J. Liebling, originally published in 1959 (North Point Press, 1986).

- “Food: America’s Top Dog” by Raymond Sokolov, Wall Street Journal, March 29,1980.

- “When Bureaucrats Cast for Fish Names, Be Prepared to Wait” by Gay Sands Miller, Wall Street Journal, May 1, 1980.

Art Information

- “Hot Dog” © dinostock; stock photo license

- “Muskrat” by Timothy Knepp; US Fish and Wildlife Services; public domain

- “Beaver with Fish Tail” from Platearius, Livre des simples médecines, ca 1480; public domain

Jeremiah Horrigan is a contributing writer at Talking Writing.

Jeremiah Horrigan is a contributing writer at Talking Writing.

Jeremiah says his conversation with Raymond Sokolov ranged from “the breeding history of Duncan to a glancing mention of baroque ivory carvings in Germany to the Byzantine intricacies of changing the transmission fluid on a high-end Scag lawn mower." He adds:

“I discovered something about food writing during my non-dinner with Ray Sokolov. For me, it can function like sports writing: I’m no better with butter than I am with a bat, but in the hands of skilled writers like Sokolov and Liebling, I can make the soufflé or the peg to home.”