TW Opinion by J.p. Lawrence

Why Young Writers Get Gonzo Wrong

I’ve had a difficult relationship with Hunter S. Thompson.

There is the Thompson of myth, the inspiration of thousands of last-minute term papers written under the influence of alcohol and drugs and duress, their authors damned by the notion that imitating the man’s process will lead to some sort of greater truth.

There is the Thompson of myth, the inspiration of thousands of last-minute term papers written under the influence of alcohol and drugs and duress, their authors damned by the notion that imitating the man’s process will lead to some sort of greater truth.

These are the students, freshmen usually, who come to their college newspaper with the idea that they’d like to try gonzo journalism. Their works, inevitably, are messy, incoherent, self-congratulatory to the point of uselessness. They titter at the idea that a writer would get drunk and take drugs.

And I, as editor of said college newspaper for the last three years, will wonder why these acolytes of the Church of Gonzo couldn’t have found themselves worshipping someone like Ernest Hemingway or Joan Didion or even Norman Mailer. Followers of those religions, at least, don’t usually spice their small insights with lengthy descriptions of their drinking schedules.

But then there is the Thompson of prolific books and magazine articles, who always had a notebook or was thinking about his notebook and something that needed to be jotted down in that notebook. The Thompson who kept searching for meaning where other journalists would stop jotting and grab a beer.

Yes, I love Thompson the writer—but, Christ, his followers!

Good writers breed bad writers, and because of this, I can marvel at Thompson classics like Hell’s Angels: A Strange and Terrible Saga or Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72 while cringing at the excesses I know his work inspires.

Take the urtext of my college contemporaries, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, an autobiographical novel (sort of) that began as a Sports Illustrated assignment and was first published in Rolling Stone in 1971. In Thompson’s over-the-top account of a massive, LSD-fueled bender, when “Raoul Duke” the journalist enters a Las Vegas hotel—the equally over-the-top Circus Circus—he finds a booth that promises to project his image into the night sky:

Hallucinations are bad enough. But after a while you learn to cope with things like seeing your dead grandmother crawling up your leg with a knife in her teeth. Most acid fanciers can handle this sort of thing. But nobody can handle that other trip—the possibility that any freak with $1.98 can walk into Circus Circus and suddenly appear in the sky over downtown Las Vegas twelve times the size of God, howling anything that comes into his mind. No, this is not a good town for psychedelic drugs. Reality itself is too twisted.

Compare this with a very real ramble from the local Thompson Youth Chapter:

I went straight to the hummus. This was quite a conundrum. The Sabra brand without debate is clearly much better than the rest, but at a higher price. Here, I had the freedom to choose the more expensive brand, but as Matteson reminded me, “With freedom, we have the opportunity to develop a will towards goodness,” and I instead decided on Kline hummus.

The hummus “conundrum” was submitted to me as a “think piece.” It’s a howler for many reasons. If you’re writing about going to the grocery store and the sum of your thoughts is whether one brand is worth the price, that’s not an essay—that’s a Sunday circular. There’s a mismatch of tone to the subject, and the self-conscious writing makes me want to shoot the narrator. (Thompson, who committed suicide in 2005, would surely aim his gun from beyond the grave.)

Thompson’s overheated prose works because of the vivid details he includes. In contrast, even if readers of the student piece can suspend disbelief, they aren’t told what makes one hummus better than another, beyond the price. Or take another recent student example:

Upstairs, the party is loud and crowded. Were all of these people really in the audience? At this point, we shall leave the audience to the spectators, the dance floor to those who actually slept last night, and slink away—whether to the bar or the bed is still undecided but in either case I am signing off. Until next time.

Why would any reader care about next time from this author’s murky vantage point? The writer has put down the notebook. Even if the goal now is to get drunk, the student reporter should be noting who’s on the dance floor, what they’re wearing, and what they’re saying. Instead, there are questions rather than details.

Why would any reader care about next time from this author’s murky vantage point? The writer has put down the notebook. Even if the goal now is to get drunk, the student reporter should be noting who’s on the dance floor, what they’re wearing, and what they’re saying. Instead, there are questions rather than details.

Many freshman gonzo-wannabes ape Thompson’s style and pyrotechnics and forget to have anything to say. It’s something most young writers struggle with. It’s baffled me—the idea of creating my voice as an author. As a young reader, I consumed great authors whole, and their style would feed my work—at least until I read the next great book, and swallowed that one whole, too.

It’s hard to have something original to say at eighteen. What do most freshmen know about love and death and war, besides what’s in books? It’s much easier to figure out a style than to know the human condition.

But if writers want to be more than imitators, it’s the path they must take. As Hemingway, another journalist-novelist, wrote in 1934:

The hardest thing in the world to do is to write straight honest prose on human beings. First you have to know the subject, then you have to learn how to write. Both take a lifetime to learn.

Anyone can be literate, but it takes a rare breed of person to understand the world and the people in it. Thompson’s style may seem free and loose, but it is never vague. Like all the writers and journalists I admire, he found examples to convey abstract concepts and well-chosen metaphors that communicate what he felt was truth. He didn’t simply state facts according to format; he interpreted them.

And he excelled at finding concrete symbols for his own anxiety. In Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72, his book about the 1972 presidential campaign (Thompson famously referred to Richard Nixon as a “crook”), his unease with the sliminess of politics is conveyed by this conversation with a pimp:

Bobo laughed, understanding it instantly. Pimps and hustlers have a fine instinct for politics. 'What you’re saying is that Nixon just cashed his whole check,' he said. 'He doesn’t give a flying fuck what happens once he gets re-elected—because once he wins, it’s all over for him anyway, right? He can’t run again.... Jesus that’s so rotten I really have to admire it.' He chuckled. 'Boy, I thought I was cynical!'

Good examples don’t mean the writing is true, but Thompson’s trick was to make the actual facts seem up for grabs. Another writer might use the same anecdote to come up with an entirely contradictory history, one with a pro-Nixon slant. Just as an author makes sense of her father by creating a character who seems suspiciously similar, Thompson’s Nixon is not Nixon’s Nixon but a fictional character, like Tolstoy’s Napoleon in War and Peace. This Nixon may not be the one true Nixon, but the character makes sense based on Thompson’s clearly defined point of view.

Meanwhile, in the following student example, the author’s opinion may be clear but the personal perspective behind the writing is not:

There’s a YouTube video full of interviews of these restorers of honor: They’re paranoid, twitchy, defensive, and angry—all traits of the insane. And they believe insane things: Obama is a gay terrorist fascist Communist Muslim who wants big government to force everyone to have abortions and steal their hard-earned Medicare money. The whole thing is insane in the membrane, insane in the brain.

Ranting and high dudgeon are easy. But it’s the thoughts of the writer, and the searching that led to those thoughts and their interpretation, that matter to readers.

Thompson’s unique and cracked understanding of America and its people is his true appeal. His reporting was relentless, whether he documented his own internal state or punched up the narrative of actual events. As the young Thompson put it in his 1959 novel The Rum Diary:

Like most others, I was a seeker, a mover, a malcontent, and at times a stupid hell-raiser. I was never idle long enough to do much thinking, but I felt somehow that some of us were making real progress, that we had taken an honest road, and that the best of us would inevitably make it over the top. At the same time, I shared a dark suspicion that the life we were leading was a lost cause, that we were all actors, kidding ourselves along on a senseless odyssey. It was the tension between these two poles—a restless idealism on one hand and a sense of impending doom on the other—that kept me going.

This is where the Youth Church of Gonzo misreads its high priest. Gonzo reporting is not an alcohol-laced shortcut to truth. It is the harder path. It is the path of the observer of human nature, of a writer who connects his own experiences with the world around him, as novelists and narrative journalists and poets and painters do.

The next time I see a student reporter force gonzo with lines like “The details of the rally itself were a blur,” I’ll pull out the real thing. Insight can’t be forced. And another author’s voice can’t be worn like a ratty sweater from the thrift store. After all, as Thompson wrote in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, “Jesus, man! You don't look for acid! Acid finds you when it thinks you're ready.”

Publishing Information

- Hell’s Angels: A Strange and Terrible Saga by Hunter S. Thompson (Random House, 1966).

- Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72 by Hunter S. Thompson (Straight Arrow Books, 1973).

- Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream by Hunter S. Thompson (Random House, 1972).

- Student quotes: These are excerpts of works submitted to the Bard Free Press in the 2010-2013 academic years. The writers are anonymous here to protect their privacy.

- Quote from “Old Newsman Writes: A Letter From Cuba” by Ernest Hemingway, Esquire, December 1934. Collected in By-Line: Ernest Hemingway. Selected Articles and Dispatches of Four Decades, edited by William White (Scribner’s, 1967).

- The Rum Diary by Hunter S. Thompson, originally written in 1959 (Simon & Schuster, 1998).

Art Information

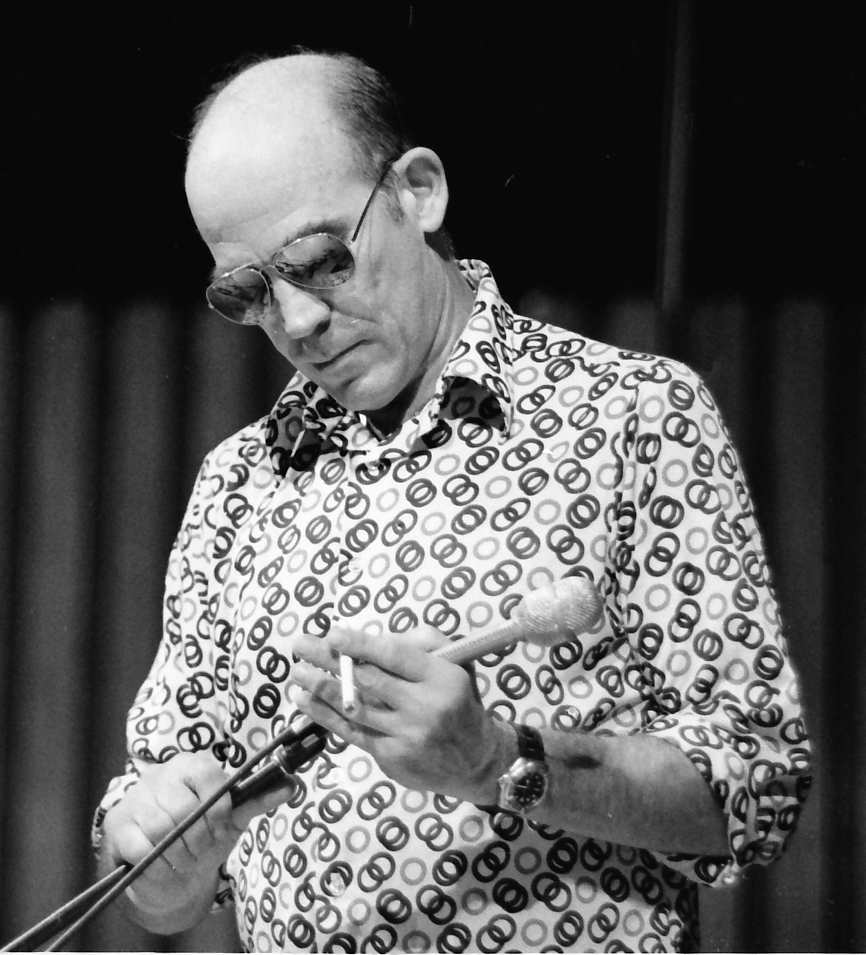

- "Hunter S. Thompson" © MDCarchive; Creative Commons license.

- "Hunter S. Thompson Portrait" © Thierry Ehrmann; Creative Commons license.

J.p. Lawrence is a contributing writer at Talking Writing.

J.p. Lawrence is a contributing writer at Talking Writing.

He is a veteran of Operation Iraqi Freedom. J.p. served in southern Iraq from 2009 to 2010 as a military journalist with the 34th Red Bull Infantry Division. He has interned at ABC News and Fox Sports North and is the recipient of a 2013 regional Emmy award.

Currently, he studies creative writing and anthropology at Bard College, where he is editor of the student newspaper.