Flash Nonfiction by Nicole Simonsen

When Nothing Else Works—and God Is Far Away

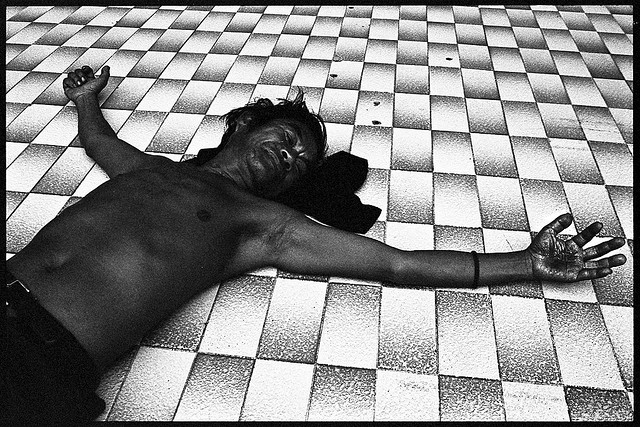

Once, while waiting for my luggage at the airport, a man I recognized from my flight hit the ground. He was large, easily twice my size, but an invisible force—a popping electrical current—was making his arms and legs dance.

Two people nearby ran over while I stood there, clutching my young daughter’s hand, one thought ticker-taping its way across my mind: oh please no, oh please no, oh please no. When a woman waved a wallet around and said he would swallow his tongue unless someone shoved it into his mouth, I finally woke from my trance.

I barked at the woman to put the wallet away. Maybe because I spoke with authority, she complied. The man’s eyes were already rolled up, his fingers contorted into claws, and he was making a glug, glug, glug sound like a clogged drain. This was a grand mal—the big bad—the mother of all seizures, but I knew exactly what to do: roll him onto his side, protect his head, keep other people away. Mostly, I wanted to shield him from stares. Seizures are, among other things, a spectacle.

I was, at that point in my life, an authority on nothing, except maybe seizures. On a bad day, my sister can have anywhere from three to four, the worst lasting fifty minutes. At the time of this incident, my sister, then 28 and younger than I was by three years, had probably suffered from 30,000 seizures, of which I’d witnessed maybe a quarter.

Caused by a rare brain tumor, her seizures cover the entire spectrum, and I know them all—petit mal, grand mal, drop, simple partial, complex partial—though my parents and I have reduced these terms to simpler ones—big or little, long or short. Fifteen seconds into a seizure, my parents know if they’ll soon sigh in relief at its brevity or have to pry her fingers from her face or try to control her violent rocking, which was once so hard she cracked a hole in a wall with the back of her head.

But until that day in the airport, I’d never seen another person have a seizure. In those initial moments when I just stood there, I felt the same dread I always do when my sister starts to moan or clap uncontrollably, and then, because it was a public place, a flush of teenage embarrassment so irrational I was thirteen years old again. I’ve learned to conquer that shame, but not what comes flooding after—a sort of resigned helplessness.

So, there in the airport, I did the only other thing left to do when a seizure is in full bloom. I whispered my mother’s mantra: “God is here. He is with me. He protects me and watches over me.” I repeated it in what I hoped was a quiet, comforting tone.

When my mother says the mantra, her voice is full of conviction, almost a command: “Say God is here. He is with me. He protects me and watches over me.” Depending on the seizure, my sister can sometimes parrot the words back even in her agitated state, her brow trenched into a deep V. “God is here?” she’ll ask, looking around the room. “God is with me?”

When I was young, I asked why God couldn’t just fix her. My mother’s answer—that God was testing our family—only begged more questions. Why us? For how long? And how many prayers would we have to say before we passed? Other families were not tested, at least not that I could tell, and I wondered what it was about them or their essential goodness that had made God look down on them and nod. Conversely, I worried that God had looked into our hearts and sensed doubt, insincerity. Or was our bad luck merely random, the end result of an impartial celestial lottery? Eventually, I tired of these questions and denounced my mother’s god, who, I imagined, witnessed my sister’s suffering from some remote billowy cloud and did nothing. Of course, the world is full of suffering, but I didn’t know the half of it then.

Even my sister, who because of the seizures and medication is childlike and innocent, has tearfully admitted that sometimes at night, curled in her bed, when she's especially sad or angry, she whispers, “Fuck you, God.” Later, in daylight hours, she'll rebuke herself over and over, until we assure her that God still loves her and heaven is seizure free. Then she worries she might not get into heaven because of her bad thoughts. “If anyone in this family is getting into heaven,” we tell her, “it’s you.”

Here on Earth, though, her seizures will continue unabated. This hard fact we have had to accept. Nothing mitigates them, not the brain surgery, not the armada of pills, not the device implanted above her heart that emits electrical impulses into her vagus nerve. So we are left, finally, with my mother’s mantra as our only defense.

We use it often. That’s probably why I said it again after the man’s seizure ended and he was only semi-conscious, his eyes open but unfocused, his breathing loud and labored as if he’d just sprinted up a mountain. I don’t know if he heard me or if the words were any sort of comfort. It’s possible they are a comfort only to the person saying them.

As he quieted, I looked up at the travelers hurrying through the sliding glass doors to cars and family members waiting to take them home. Someone wondered out loud if we should call an ambulance, but then the wallet lady said his brother was coming to pick him up and we should wait. And that’s what we did. We waited around to make sure the man would be okay, that someone would come—and it strikes me now that maybe this was God in action, those strangers who held the man’s hand and waited.

Art Information

- "Without Love You Are Nothing #6/6" © Ronn aka "Blue" Aldaman; Creative Commons license.

Nicole Simonsen’s first published story appeared in the November 2013 issue of Talking Writing. Since then, her work has been published in various journals, including SmokeLong Quarterly, Necessary Fiction, and Full Grown People. This year, one of her stories won the Editor’s Prize at Fifth Wednesday Journal. She’s currently working on a collection of stories and a novel. She teaches English at a public high school in Sacramento, California, and lives nearby with her husband and children.

Nicole Simonsen’s first published story appeared in the November 2013 issue of Talking Writing. Since then, her work has been published in various journals, including SmokeLong Quarterly, Necessary Fiction, and Full Grown People. This year, one of her stories won the Editor’s Prize at Fifth Wednesday Journal. She’s currently working on a collection of stories and a novel. She teaches English at a public high school in Sacramento, California, and lives nearby with her husband and children.