Theme Essay by Anna Shane Stadick

The Value of Spiritual Wrestling on the Page

God died when I was diagnosed with Bipolar I Disorder.

The first year, I got by with memorized answers: “God is in control” and “God doesn’t give you anything you can’t handle.” True, I thought, but not very comforting when squatting naked before a nurse so she could make sure I didn’t have a weapon lodged in my vagina. Still, having been raised in the church, I knew exactly what to say when well-intentioned friends texted me Bible verses. When I was first diagnosed in 2013, I had to cover up that I didn’t care about God being in control or what God’s plan for my life was—I wanted my own plan. A plan that didn’t involve a mental breakdown.

The second year, I again found myself lying in a hospital bed on suicide watch. There was no meaning in my pain; there couldn’t be. I couldn’t parrot the Christian answers anymore. All I could think was God is dead, God is dead, God is dead.

What I meant was: If God is alive, I hate Him.

That next year was simply disappointing. I was tired of doing everything right—the meds, the shrink, the counseling—but the depression came like a familiar and unwelcome friend. I couldn’t pray. I couldn’t talk to friends. I couldn’t even bring myself to write again.

I wallowed in my purposelessness, comfortable only in my anger at God. I’d grown up Protestant, part of a nondenominational church of staunch believers, and His presence haunted me. I couldn’t walk away from my faith, not when I’d known Him so intimately since childhood. But I was furious with someone I didn’t want to exist.

The depression kept me from my writing for too long. Before the bipolar diagnosis, writing was an everyday thing, not something I thought about. After bipolar took over my life, I’d sit down and stare at the blinking curser on the blank Word document. I’d write a few words and begin to cry, annoyed with my overwhelming emotions. After a few minutes, I’d close the laptop and go back to my nap. It’s too hard.

I debated giving up writing. Maybe it didn’t have to be the dream career I’d always wanted. It didn’t even have to be a hobby. Maybe I could let it go for good.

The year crawled along, and my health improved. But without writing, I couldn’t process anything that had happened to me. I tried talking it through with my husband, my parents, my sister. They did their best to encourage me, and while I’m grateful for their kind words, it wasn’t enough.

I knew what I needed to do, but months went by before I sat in front of my computer again. The words were sluggish; every sentence took too much effort. Weeks slid by, and it became easier. Three more months, and I was writing slowly but regularly.

First, I raged against God. I created angry blog posts about the silence of my Creator and deleted them for fear of judgment. I turned to my journal, where I didn’t have to delete anything. I began to write down question after question:

Why me? Why bipolar? Why have I not been good enough for you, God? Why can’t I hear you anymore?

Somehow, writing it down helped validate my disappointment. It was on paper, so it was real. Writing didn't provide answers, but it gave me an outlet for my frustration.

My journal entries reflected my erratic emotions. Anger into self-pity, self-pity back to anger. How could You do this to me when I prayed so hard and believed so deeply? How could You want this for me? Have my prayers proved meaningless? God, you hate me. And I hate you, too. Anger into sadness, and sadness into a quasi-acceptance. I want to believe again. I do, God. Help my unbelief. And when I thought it was all worked out? Back to anger. You abandon me? Fine. I’ll abandon you.

But as my feelings continued to bounce back and forth, I learned to live with the uncomfortable. Being a Christian, I learned, is not about having all my questions tidied up with a giant red bow. Being a writer is not about having all the answers, either. To live in the unknown, in the uncomfortable, is a challenge for Christians and writers alike.

After several months of journaling, I began writing creative nonfiction pieces and short essays. I realized that my pain could help my narrative voice. Exploring my pain could, perhaps, help others.

And other writers helped me. Louise DeSalvo’s 1999 book Writing as a Way of Healing encouraged me to look for beauty in my own faith search. As DeSalvo says:

Why, then, should we write? Because writing permits the construction of a cohesive, elaborate, thoughtful personal narrative in the way that simply speaking about our experiences doesn’t. Through writing, suffering can be transmuted into art.

The wrestling I’ve done isn’t always welcome in Christian circles, so the page has become my private platform. I call God out on His seeming inconsistencies, something a lot of Christians are afraid to do. But I think God prefers our questions to ambivalence. Questions are personal. He’d rather I struggle to know Him and keep my faith than simply walk away.

Because of my writing, I feel a new kind of intimacy with Him. I no longer view God as a detached being, punishing me through illness. I don’t think He’s ambivalent about my mental suffering. My writing has significantly influenced my understanding of who I believe God is and, really, who I am. When I write about God, even raging or in pain, I’m spending time in His presence, and He in mine.

Writing has become a relationship. It’s become sacred.

Publishing Information

- Writing as a Way of Healing: How Telling Our Stories Transforms Our Lives by Louise A. DeSalvo (HarperOne, 1999).

Art Information

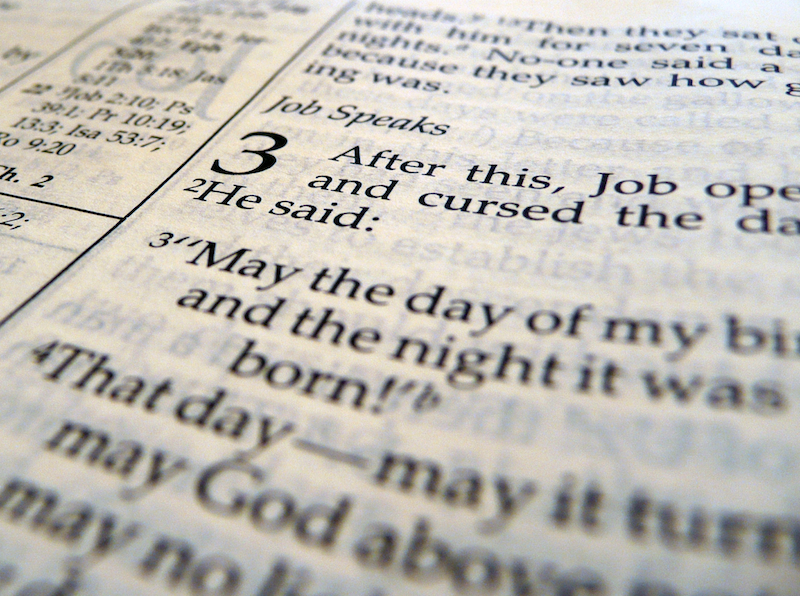

- “Brief” (Job 3:2) © Brett Jordan; Creative Commons license.

Anna Stadick is a graduate of Wheaton College and currently pursuing an MFA in creative writing at Goddard College. She lives in Denver, Colorado, with her husband Rob and fluffy dog Beowulf. She enjoys hiking, biking, and gluten-free baking.

Anna Stadick is a graduate of Wheaton College and currently pursuing an MFA in creative writing at Goddard College. She lives in Denver, Colorado, with her husband Rob and fluffy dog Beowulf. She enjoys hiking, biking, and gluten-free baking.