Feature by Michael Milburn

Do We Learn More in Class or from a Writer's Work?

As a junior at Harvard thirty years ago, I took a poetry writing class with the eminent poet and translator Robert Fitzgerald. The class was called “Versification” and involved writing in various meters and forms—iambic pentameter, Greek alcaics, sestinas. Enrollment was limited and admission coveted; the Harvard literary magazine regularly printed formal poems that the master had presumably praised.

Or faintly praised. Fitzgerald evaluated poems with an eccentric system of penciled abbreviations: “p.b.” (pretty bad); “n.t.b.” (not too bad); “n.b.” (not bad); “n.a.a.b.” (not at all bad).

I can’t remember anyone getting a straight “b.,” though Fitzgerald hardly shrank from censure. For our final assignment, he freed us from metrical constraints and invited a poem in free verse. On mine he dispensed with his code to scrawl, “Amusing for this kind of thing.” When I showed the paper to a friend, she said, “What a snob.”

I agreed. Fitzgerald’s class, in which I never received a grade higher than “n.t.b.,” turned out to be my first and last foray into writing formal poetry.

But the majority of his students loved his approach: the strict prosodic demands, the stinginess with praise. Even his personal quirks endeared him—he walked around campus in a beret and occasionally punctuated his spoken sentences with audible clicks of his tongue.

I still come across affectionate reminiscences of Fitzgerald by his former students. In his 1998 essay “Learning from Robert Fitzgerald,” Dana Gioia calls him “my favorite teacher at Harvard”; in a 2003 interview, the poet April Bernard refers to “my beloved, wonderful, adored teacher, Robert Fitzgerald.”

I found Fitzgerald’s abbreviations, which he’d borrowed from Dudley Fitts (his own writing teacher), precious and condescending. Were they supposed to be motivating? And while the course’s title implied a focus on prosody, I hadn’t expected the translator of Homer and Virgil to segregate form and content so completely. Fitzgerald would tersely point out where my meter was off or a rhyme strained too hard, but declined to address, much less critique, other aspects of my poems.

I was passionate about poetry and becoming a poet, and eager to learn from my betters, but I didn’t share my fellow students’ delight in Fitzgerald’s grudging appraisals. Whatever his virtues as a literary taskmaster, he was the wrong kind of writing teacher for me.

"A View to Instruct"—or Not?

I rejected the Fitzgerald approach when I began to teach writing myself. Yet he remains one of my most influential mentors, for a reason that has nothing to do with my time in his classroom.

Two years after graduating from college, I came across his 1956 essay “A Note on Ezra Pound, 1928-56,” in which he reflects on Pound’s life and work. The quality of Fitzgerald’s prose, combined with his sensitivity as a critic and biographer, made me want to write my own essays about poets and poetry.

This desire is still with me. I’m still guided by the lessons in clarity and compression that I learned from his practice rather than his pedagogy. Of Pound’s influence, for example, Fitzgerald wrote more than half a century ago:

It is useful to learn things from someone who knows them and imparts them with a view to instruct. But it is useful and also delightful to find things out for oneself. The work I have been doing lately would have been done otherwise and not so well if it had not been for Pound’s work and his critical stimulus.

That makes Fitzgerald both the worst kind of writing teacher—one who rations praise and doesn’t advise on how to improve a piece—and the best kind—one whose example, either through his teaching or his writing, contains lessons that endure longer than any semester or critique.

I felt no affinity for Fitzgerald’s penciled put-downs, but still pass everything I write under the eyes of the teacher I have internalized from his work. While the latter version of Fitzgerald is no less exacting than the one I encountered in the classroom, his judgments are not only acceptable—they’re inspiring.

Over the years, I have worked with many writing mentors—in high school English classes, in college and graduate workshops, in a long-term tutorial after college, and in collaboration with editors preparing my work for publication. For the past twenty years, I have taught writing to adults and to college, high school, and middle school students. All the while, I have been reading works by and about writers I admire with an eye toward learning from their processes and their art.

Certain of my teachers may have left their mark on this particular sentence or paragraph, or on the way I structure an argument, frame an anecdote, outline, draft, revise. This essay would probably have come out differently if I’d had different writing teachers or none at all. But maybe the best measure of my education is the fact that I have kept on writing. My teachers served less as instructors than as motivators or role models, inspiring me more than they informed.

As a teacher, I’m probably a blend of informer and inspirer, but ultimately my students will decide. They’ll take what they need and leave the rest, as I did with Fitzgerald.

Studying the Great Stylists

I believe a teacher’s impact depends in large part on timing—particularly the timing of encouragement or discouragement relative to a student’s age.

Some of my middle school students are so galvanized by praise that it hardly seems to matter who supplies it; a glowing comment about a poem ignites their literary ambition on the spot. If more of my early teachers had bestowed “not too bad”s rather than enthusiastic approval of my efforts, I doubt I’d have persevered.

As all schoolteachers know, students tend to remain deaf to instruction until they are ready to hear it. For Raymond Carver, this moment of receptivity occurred in John Gardner’s freshman writing course at Chico State College. In a recent Carver biography, he’s quoted as explaining:

As all schoolteachers know, students tend to remain deaf to instruction until they are ready to hear it. For Raymond Carver, this moment of receptivity occurred in John Gardner’s freshman writing course at Chico State College. In a recent Carver biography, he’s quoted as explaining:

I was at that particular point in my life where nothing was lost on me. Whatever [Gardner] had to say went right into my bloodstream and changed the way I looked at things….

Timing was everything for me as a student, too, more so than proximity. In high school and college, some of my most important writing mentors weren’t my actual teachers. Certain literary biographies and Paris Review interviews—with T.S. Eliot, William Carlos Williams, John Berryman, James Merrill, Elizabeth Bishop—affected me more than any class.

My discovery that Merrill had made poetry out of a background similar to mine placed him among my most influential role models. In these cases, the absence of the person—or more accurately the personality—might have been an advantage, allowing me to take in the information unaffected by charisma or its absence.

“Place the emphatic words of a sentence at the end.” This precept from Strunk and White’s Elements of Style is responsible for countless revisions I’ve made to my prose over the years. The lasting observable impact on my writing of this and other commandments qualifies these authors as indispensable teachers.

The same goes for Edward Hoagland, James Baldwin, Randall Jarrell, Joan Didion, and Robert Hass. I am certain that my own essays would look different if I had not read theirs. I began reading Hass in my twenties, and the anecdotal, associative style of his essays on Tomas Tranströmer, James Wright, and Robert Lowell motivated me to try my own hand at critical prose.

Asked about the importance of this kind of influence to a young writer’s development, poet Billy Collins said in a 2009 interview:

[T]he real teachers…are not conducting workshops; they are waiting all night in the dark on the shelves of the library to be opened and read and imitated…. One learns to write by writing, and then only if the writing is inflamed by jealousy caused by reading poets better than one will ever be.

Emulating great stylists until one’s own style emerges—what writer could deny this as the essential recipe for his or her education? The tracks of mentors such as Jarrell and Hass were more conspicuous in the writing I did as a young man; as I enter my fifties, they have receded to form a kind of foundation for my voice.

The best teachers, whether in the classroom or on the page, teach us to internalize what we have learned so that we no longer need them beside us.

Internalizing the Critical Voice

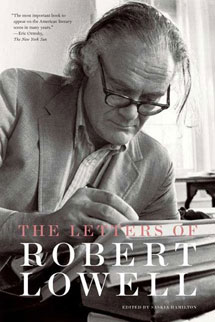

For my master’s thesis on Robert Lowell, I studied the collection of his papers housed in Harvard’s Houghton Library. One day, I came across a letter from Robert Frost assuring Lowell, in his twenties at the time, that he would eventually be able to judge the merit of his own work.

I empathized with Lowell’s uncertainty. I could never tell which of my poems were any good. After graduating from college, I had continued to meet with one of my workshop teachers, Ellen Bryant Voigt, sending her my poems and visiting her once a week to discuss them. It frustrated me that I could never predict which poems she would respond to enthusiastically or tepidly.

I empathized with Lowell’s uncertainty. I could never tell which of my poems were any good. After graduating from college, I had continued to meet with one of my workshop teachers, Ellen Bryant Voigt, sending her my poems and visiting her once a week to discuss them. It frustrated me that I could never predict which poems she would respond to enthusiastically or tepidly.

Voigt was the opposite of Fitzgerald, a proactive critic who offered explicit strategies for clarifying and completing my poems. I thrived on this guidance, but reached a point where I could not consider a poem finished or worthwhile until she had pronounced it so. I tried to internalize her critical voice, but couldn’t, even long after we ceased meeting.

Was this because I had adopted her suggestions without sharing her sensibility, or had her confidence in diagnosing my poems undermined mine? My difficulty in weaning myself from her influence made me wonder if part of a teacher’s job is to show his or her students how to thrive on their own.

Three decades later, I’m still often unsure of my poems’ merits, but feel less in need of assistance finishing them. Writers always remain blind to aspects of their own work, but the amount of editing they require diminishes as they gain experience.

Discussing Carver’s relationship with his editor Gordon Lish, Charles McGrath observes in a 2007 article: “[T]he evidence…suggests that he eventually outgrew Mr. Lish…. Over time he learned how to be his own best editor.”

It makes sense that motivated writers will pay attention to which suggestions improve their work and apply these to their next effort. In this way, we carry our best teachers and editors with us, heeding them long after the relationship has ended.

Forty years after leaving Fortune magazine, John Kenneth Galbraith noted in a 1986 interview that “I can still, to this day, not write a page without the feeling that Henry Luce is looking over my shoulder and saying, ‘That can go.’”

I believe this is the most tangible long-term effect teachers can have, as important as inspiring young writers to devote themselves to the craft. The ideal teacher would combine the two, though in my experience not all writers dedicated to their work are willing to apply equal dedication to their students.

”Nature's Most Unconfident Species"

Kurt Vonnegut said he couldn’t teach people to write, but like an old golf pro, he could go around with them and perhaps take a few strokes off their game. No doubt some teachers achieve a more dramatic transformation in their students than Vonnegut, and some writers long removed from the classroom still count on friends or editors to overhaul their drafts.

The novelist Ian McEwan says he consults three friends for three different kinds of critique. In the 1997 introduction to her Selected Stories, Alice Munro credits her New Yorker editors Charles McGrath and Daniel Menaker for help in revising her short stories:

I know what I want to happen and where I want to end up and I just have to keep trying till I find the best way of getting there. I should mention here that I don’t always have to do all this work by myself. An editor who is also an ideal reader can work with you on these final shifts and slants in a seamless, amazing collaboration.

Munro doesn’t say whether she thinks of the stories she submits to the New Yorker as done. But she remains open to revision or incorporating her editors’ input as part of her writing process. (Of course, few fiction writers are fortunate enough to have editors like McGrath and Menaker offering such input.)

I can’t imagine showing anyone work I didn’t consider finished. My pleasure in writing comes from doing everything in my power to make a piece say what I want in the way that I want. Afterward, I welcome feedback and am happy to revise, but if I tried to accommodate another vision before realizing mine, both the process and the product would feel disjointed.

Also, in the early stages of writing I’m too susceptible to discouragement to risk someone else’s opinion. I’m capable of dismissing a piece as a failure right up to the final draft. Even then, my inability to come up with an ending or to revise a section to my satisfaction can cause me to abandon the whole. If a reader I respected reacted unenthusiastically to a piece I did not yet feel confident about—in other words, any work in progress—I’d probably quit on it.

Such sensitivity may sound immature, but I think it makes me a good teacher for middle and high school students, who tend to doubt not just specific pieces of writing but their overall ability.

In his 2009 memoir Writing Places, William Zinsser, whose nonfiction course at Yale produced many distinguished journalists, calls writers “one of nature’s most unconfident species, in constant need of assurance that they are not doomed souls.” For this reason, I would never critique a writer of any age without incorporating encouragement, even if I have to search for something to praise.

Carver’s biographer Carol Sklenick describes the impact of John Gardner’s constructive approach in this way:

Gardner was sure of himself and a relentless marker of manuscripts. He deleted words, phrases, and sentences…. Ray was sensitive to criticism, but Gardner found enough to praise, writing ‘nice’ or ‘good’ in the margin now and then. When he saw those comments, Ray’s ‘heart would lift.’

Simply pointing out flaws or being stingy with approval like Fitzgerald strikes me as counterproductive and, to a young writer, potentially demoralizing. I benefit as much from hearing what works in my writing as what doesn’t, but some writers are content to hear only critical comments.

Ayelet Waldman, asked in a 2009 radio interview what it’s like to edit and be edited by her husband Michael Chabon, said:

When we’re editing other people, we always say, you have to do a praise sandwich, like lots of praise and then the criticism and more praise. When it’s the two of us, we just skip the bread. We go right to the problems, and we’re brutal.

I have heard of teachers, usually prominent poets working in colleges or MFA programs, who treat their students like boot camp recruits, savaging their poems in workshops. I am all for portraying writing as an exacting craft, particularly to older students; some people might be motivated by a ruthless approach. But such discouragement may do more damage than good, boosting the teacher’s vanity at the expense of the students’ self-esteem.

Motivation from Within

Several prominent poets besides Fitzgerald taught at Harvard in the 1970s and 1980s. I also took workshops with Robert Lowell and Seamus Heaney. While neither qualified as a great teacher in terms of instruction or editing, their classes were invaluable to me.

Lowell was ill and had less than a year to live when I took his course, and the poems that I showed him were, like most of my classmates’, derivative of his own. He neither encouraged nor discouraged this emulation; he offered only general comments on the work I submitted and a few lines of praise in his end-of-term evaluation.

Lowell was ill and had less than a year to live when I took his course, and the poems that I showed him were, like most of my classmates’, derivative of his own. He neither encouraged nor discouraged this emulation; he offered only general comments on the work I submitted and a few lines of praise in his end-of-term evaluation.

Yet, his intelligence and stature were such that listening to him talk about poets and poems for eight weeks, and receiving his approval, however cursory, was the highlight of my writing education.

From Heaney, too, I learned less about making poems than about how to carry myself as a poet. He rarely suggested specific revisions, perhaps out of a reluctance to impose his distinctive style on his students. And while it frustrated me to leave classes and conferences with no clue how to fix poems that he said needed fixing, Heaney illuminated me in other ways.

As with Lowell, it was instructive to hear him discuss poetry and read his own and others’ work out loud. In the early ‘80s, he was new to Harvard and just beginning to enjoy the success and fame that would culminate in his Nobel Prize in 1995. I respected him for retaining his modesty not only in class, but with the admirers who thronged his readings and greeted him on campus walkways. While not an effective editor, at least of student poems, Heaney was an exemplary person and poet, which for my purposes at the time was enough.

Celebrity or virtuosity alone doesn’t compensate for a teacher’s lack of pedagogical skills. For every Heaney who edifies by example, there are good poets who insist on shaping student writing to their own styles and famous ones who alienate through indifference or use the classroom to nurture their egos.

I mentioned these dangers recently to a friend in her mid-fifties who was applying to MFA programs in poetry. In researching different faculties, she wondered whether to seek out poets she admired or had heard of—or to allow for the possibility that an undistinguished writer might turn out to be a good teacher.

Whatever quality of instruction she receives, a writer’s motivation in the end comes primarily from within. Teachers have the power to stimulate, sustain, or extinguish that spark. What I hope for my friend is that feedback from faculty and students, as well as the abundant required reading, will turn her into her own best teacher.

Publication Information

- “Learning from Robert Fitzgerald” by Dana Gioia, The Hudson Review, Spring 1998.

- “Interview: April Bernard” by Reb Livingston, Post Road Magazine, Issue 7, 2003.

- “A Note on Ezra Pound, 1928-56” by Robert Fitzgerald, The Kenyon Review, Autumn 1956.

- Excerpt on NPR Books from Raymond Carver: A Writer’s Life by Carol Sklenicka (Scribner, 2009).

- “A Conversation with Billy Collins” by Robert Potts, The Coachella Review, Fall 2009.

- “I, Editor, Nay—Author” by Charles McGrath, Charles, New York Times, October 28, 2007.

- “Conversation with John Kenneth Galbraith” by Harry Kreisler, Institute of International Studies, U.C. Berkeley, March 27, 1986.

- Selected Stories by Alice Munro (Knopf, 1996).

- Writing Places: The Life Journey of a Writer and Teacher by William Zinsser (HarperCollins, 2009).

- “Ayelet Waldman’s Memoir Of A ‘Bad Mother’,” radio interview by Terry Gross of “Fresh Air,” WHYY, May 5, 2009.

Art Information

- “Robert Fitzgerald, Consultant in Poetry, 1984-85″ © Myriam Champigny; Library of Congress Digital Reference Section

- “Seamus Heaney” (Uppingham School, 1970); public domain

Michael Milburn teaches high school English in New Haven, Connecticut. His book of essays, Odd Man In, was published in 2005 (Mid-List Press). His third book of poems, Carpe Something, will appear in 2012.

Michael Milburn teaches high school English in New Haven, Connecticut. His book of essays, Odd Man In, was published in 2005 (Mid-List Press). His third book of poems, Carpe Something, will appear in 2012.