Theme Essay by Wendy Glaas

Why the Pop Master No Longer Embarrasses Me

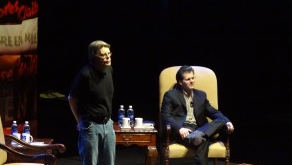

Last December, I attended a very public “conversation” between Stephen King and his longtime friend Andre Dubus III. Very few of the 6,000-plus seats at the Tsongas Center at the University of Massachusetts in Lowell were empty.

The crowd was split evenly between men and women, but most were in my age group (north of 30). One woman said she’d flown from Chicago to see King; another had driven nine hours from Pennsylvania. During the Q&A, several started with a similar story:

Oh my God, I’m talking to Stephen King! [audience laughs] So, I was about eleven when I discovered you. I read IT and then read everything I could get my hands on….

Chancellor Marty Meehan introduced King, noting that the author and his wife Tabitha had donated his entire speaking fee to student scholarships. A burble of “what a nice guy” and “classy move” arose in the seats around me.

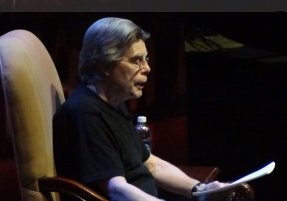

Dubus and King took the stage together. In his blazer, Dubus looked appropriately professorial and writerish. King wore jeans and a black T-shirt, as if he were literally taking time out from writing to be there.

“It’s scary as shit to see so many people,” King said. “This is my first stadium show!”

Then he sat cross-legged in a chair. As Dubus spoke of King’s accomplishments, King occasionally interjected. When Dubus noted that fifty of King’s books have been adapted for TV or film, King quipped, “Some of which were good.”

“By the way,” Dubus said to King at another point, “you probably don’t know that you’ve outsold Charles Dickens times two. That’s incredible.”

King: “He didn’t have e-books.”

And later:

Dubus: “In the green room [before the show], we were telling dirty jokes.”

King: “You were telling dirty jokes. I was talking about literature.”

After watching him parry words with the erudite Dubus, I realized, finally, that what I like best about King is the man himself: his no-shit demeanor, his working-class roots, his struggles with addiction and recovery.

But the fact remains that his work has entered my psyche thoroughly, like tentacles from his nightmarish creations. He’s one of the most famous writers alive—a touchstone in the popular imagination—yet my love-hate relationship with Stephen King reflects more than an intellectual assessment of his writing or star status.

It reflects me. It’s about what I expect of writers who move me and hook me and rattle me. It’s about why succumbing to Pet Sematary in high school made me feel like a bibliophilic lightweight—and maybe still does, a little.

On Reading Stephen King

Once upon a time, I read his books nearly as often as he produced one. I was in seventh grade when I first read Salem’s Lot, after catching bits of the movie on TV. Next came The Stand, The Shining, The Dead Zone.

I would pedal over to the library on my bike, then hide his books from my mom, who worried about her youngest developing morbid thoughts.

By the time I was in college, though, the fact that I’d enjoyed some of his bestsellers embarrassed me. King had become a guilty pleasure I had to keep secret. After all, I was supposed to be carrying around books by William Faulkner or various Norton anthologies.

I didn’t think about Stephen King much again—until I was in my twenties. Literary friends of mine urged me to read The Dark Half and Dolores Claiborne. I decided to give him another shot, and, here and there, I felt the old thrill.

I didn’t think about Stephen King much again—until I was in my twenties. Literary friends of mine urged me to read The Dark Half and Dolores Claiborne. I decided to give him another shot, and, here and there, I felt the old thrill.

But I set him aside again after reading his 1991 novel Needful Things. At that point, I had my analysis of his work down pat: King spends about three-quarters of any given story setting the stage for an inevitable showdown which—once it comes—is pretty short. I’m left wondering, Is that all there is?

Until he comes back to haunt me. Again.

Last summer, more than a decade after I’d dismissed Needful Things, I happened to pick up King’s 2000 nonfiction primer On Writing. Suddenly, I found myself delightfully surprised, inhaling it during my daily subway commutes.

In particular, I was struck by one passage in the introduction. King says that Amy Tan complained to him once that nobody at her book signings and readings had ever asked her about the language. King then throws down his gauntlet:

[M]any of us proles also care about the language, in our humble way, and care passionately about the art and craft of telling stories on paper.

It’s true that I’d never noticed King’s language as I have that of, say, T.C. Boyle, who casually tosses around words like oneiric. So, I decided to give King another chance, this time focusing on his “art and craft.”

For my new challenge, I chose Just After Sunset, his 2008 collection of short stories. I read as many as I could during my hour-long commutes on the Boston MBTA—and what I came to call the “subway project” crystallized my mixed reaction to his work.

The Subway Project

As a kid and secret King reader, tucked into bed in an upstate New York town not so different from the working-class landscapes of his books, I also nursed a desire to be a writer. Yet real writers, I thought, read James Joyce, John Steinbeck, Richard Russo—not dime-store novels about vampires.

King seems well aware of the way he polarizes readers. In On Writing, he notes that “a good deal of literary criticism serves only to reinforce a caste system which is as old as the intellectual snobbery which nurtured it.”

I’ve googled such phrases as “Is Stephen King a real writer?” and turned up several recent hits, including a 2012 piece by Dwight Allen (“My Stephen King Problem”) in the Los Angeles Review of Books. A rebuttal by Erik Nelson in Salon refers to Allen’s piece as a “bile-drenched, meandering hatchet job.”

I’ve googled such phrases as “Is Stephen King a real writer?” and turned up several recent hits, including a 2012 piece by Dwight Allen (“My Stephen King Problem”) in the Los Angeles Review of Books. A rebuttal by Erik Nelson in Salon refers to Allen’s piece as a “bile-drenched, meandering hatchet job.”

Nelson is not wrong; it’s unfair to dismiss King as a hack who spits out genre trash. Some of his best novels and short stories, like The Shining, are brilliant.

In several stories in Just After Sunset, for instance, King sucks the reader into the scene. In “Harvey’s Dream” (first published in the New Yorker), I was in the kitchen right along with the long-married couple, seeing the toll age had taken:

Then one day you made the mistake of looking over your shoulder and discovered that the girls were grown and that the man you had struggled to stay married to was sitting with his legs apart, his fish-white legs, staring into a bar of sun, and by God maybe he looked fifty-four in either of his best suits, but sitting there at that kitchen table he looked seventy.

The quiet exasperation of Harvey’s wife evolves into something more unsettling as her husband relays a nightmare he had about one of their grown daughters being killed by a car. Slowly, bits of “evidence” suggest that this wasn’t just one of Harvey’s bad dreams: A dent in a neighbor’s car. A dark stain with the dent.

I‘m not the first to think that King could use an editor. But at times, he’s wonderfully succinct in his descriptions. In “Ayana,” a story about a mysterious young girl with the ability to perform miracles, he captures one key character in a single line: “[H]e had a slightly dangerous look, like a sailor two weeks into a shore leave that will end badly.”

Still, during the subway project, I sometimes glanced sheepishly around at my fellow T riders, wondering what they thought of me reading Stephen King when others were flaunting Dostoevsky. (Even in my gym, where I indulge in US Weekly on the elliptical, I see the New Yorker, Opera, and Cell in the members’ reading library.)

This is Cambridge, and reading is serious business. Even on the T, when most commuters are half-awake.

A Very Shitty Story

I didn’t read the thirteen stories in Just After Sunset in sequence. I chose them based on length and how much commuting time I had during a particular clip. Without realizing it, I wound up reading some of the stronger ones like “Ayana” and “Harvey’s Dream” first—stories that had far more to do with psychological terror than goofy monsters.

I’d made my way through a little more than half of them by the time I took the book along on an airplane flight last November. And somewhere over the mid-Atlantic states, I stopped reading King. The SkyMall catalog seemed more enticing.

I started grinding to a halt with “A Very Tight Place,” a story about two longtime neighbors feuding over a parcel of property. Grunwald (unsubtly nicknamed “The Motherfucker”) manages to get Johnson, the protagonist, to an empty construction site and forces him into one of the site’s fragrantly full porta-potties. After some jarring homophobic rants, Grunwald leaves Johnson for dead, trapped in the porta-potty.

Johnson spends the night in his lavatory prison, cold and fatigued, but with his survival instinct intact. He realizes that the only way out is not through the steel-clad walls of the porta-potty, but through the pool of human waste.

King takes fifteen pages to describe Johnson’s excruciating shimmy, pages I skipped.

Next, I flipped to “N.”—and that’s the story that had me reaching for SkyMall.

It begins promisingly enough. It’s told via therapist notes and focuses on a man (N.) who’s developed obsessive-compulsive tendencies. They’ve come to control his life, but it wasn’t always so: The year before, something mysterious happened in a clearing called Ackerman’s Field that caused him to develop his frenetic counting and touching:

‘Tell me about Ackerman’s Field.’

He sighs and says, ‘It’s in Motton. On the east side of the Androscoggin.’

Motton. One town over from Chester’s Mill. Our mother used to buy milk and eggs at Boy Hill Farm in Motton. N. is talking about a place that cannot be more than seven miles from the farmhouse where I grew up. I almost say, I knew it!

I don’t, but he looks over at me sharply, almost as if he caught my thought. Perhaps he did. I don’t believe in ESP, but I don’t entirely discount it, either.

‘Don’t ever go there, Doc,’ he says. ‘Don’t even look for it. Promise me.’

I give my promise. In fact, I haven’t been back to that broken-down part of Maine in over fifteen years. It’s close in miles, distant in desire.

There are many pages like this, along with N.’s compulsive behavior: fidgeting with the doctor’s vase of tulips, positioning them next to the box of Kleenex.

Finally, N. describes being in the field. He says he saw human faces on the trees. He says there was a monster with “sick, pink eyes” and a black flattened snakehead.

WTF? I snapped the book shut.

I harrumphed to myself about King being great at setting the stage for dread, but then when you actually see what’s in the middle of the clearing, it’s anticlimactic. It’s stupid.

Or so I thought.

On Getting Stephen King

One month later, at his U-Mass stadium show, the pop master hooked me with another tentacle. The middle portion of the show was devoted to the “world premiere” of King’s unpublished short story “The Afterlife,” which he read to the audience.

In this story, a man departs his hospital bed after dying from colon cancer and meets with what appears to be a manager in a nondescript office (purgatory). After a recounting of the man’s life, including misdeeds, small and large (not scheduling a colonoscopy, not stopping a fraternity gang rape when he saw it happening), he’s given a choice between two doors: repeat the same life all over again but without any memory of the events, or move on to the afterlife.

The protagonist has obviously chosen to repeat his life again, many times, and has still made the same mistakes. (I won’t spoil the ending.) The audience sat in reverent silence as King read, and burst into applause at the end.

The protagonist has obviously chosen to repeat his life again, many times, and has still made the same mistakes. (I won’t spoil the ending.) The audience sat in reverent silence as King read, and burst into applause at the end.

After seeing this love for him firsthand, I felt badly about giving up on Just After Sunset. I decided to go back and finish “N.,” at least.

The second time around, I made it beyond the writhing serpent-like creature in the woods. I feared for the therapist who’d been warned to stay away from the clearing by his patient—but who can’t. As a result, the therapist develops the same OCD tics.

I got it then—or Stephen King got to me. An otherwise intelligent person is undone by natural curiosity:

There’s nothing out there.

Just some rocks.

I saw with my own eyes.

I swear there’s nothing out there, so stay away.

“What a Nice Guy”

During his conversation with Dubus, King exuded the ordinary-guy presence I expected from On Writing. But there were reminders that he’s not just like us. Someone who’s gone from sitting at a typewriter beside a rumbling washing machine to selling 350 million books has stories to tell—and for a writer like me, his rise to celebrityhood is the real hook.

As he recounted to the audience of thousands, his first Are you someone famous? question came in the 1970s, sometime after Carrie, at a Nathan’s Hot Dog in New York. A dishwasher asked him, “Are you Francis Ford Coppola?”

A then-hirsute King said yes and gave the dishwasher an autograph.

He knew he’d truly made it, though, when he was having dinner with Bruce Springsteen in the 1980s at a café in Greenwich Village. According to King, a teenage girl breathlessly approached the table. King assumed she wanted to talk to Springsteen. (Springsteen even started going through the motions of looking for a pen.)

But then “she never fucking looked at him,” King said with a grin. The teenage girl was a King fan. Dubus whooped and high-fived him, and we collectively roared.

That a young woman would blow off Springsteen and focus only on a geeky author reminded me of why I was taken by On Writing: You can’t help but root for King. Even though I picked up the book knowing full well he had the GDP of a small country, I still was rooting for him not to take that extra job washing sheets at New Franklin Laundry.

And, okay, there was a little bit of Revenge of the Nerds going on, too. If King felt vindicated in that moment by upstaging a rock god, we felt it vicariously.

When asked by another questioner about how he can tell when his vocabulary’s “becoming too onanistic,” King replied: “The only thing you can do is use your best judgment. I want to tell stories, but I love the language…. I don’t aspire to be lyrical. I want to write as best as I possibly can.”

So, it is the language, stupid—but not in the way literary critics think.

Later, when I told people I’d gone to see Stephen King, they almost unanimously exclaimed, “Damn! I wish I’d known he was here.”

With more than sixty books under his belt, some are bound to be stronger than others. Revisiting “N.” made me get over my initial “Oh, come on” reaction. There really was more to its initial setup, and by the end, I knew why I cared.

As an adult, I see the world in shades of gray. The actions of people, groups, even whole governments are often morally ambiguous. In contrast, King’s books and stories clearly delineate good and evil. Simple? Sure. But it’s comforting knowing exactly who the Bad Guy is. Loving Stephen King is like loving the solid beliefs of my childhood. It’s like loving myself and everything I need in order for life to make sense.

Publishing Information

Publishing Information

- Needful Things: The Last Castle Rock Story by Stephen King (Viking Press, 1991).

- On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King (Scribner, 2000).

- “My Stephen King Problem: A Snob’s Notes” by Dwight Allen, Los Angeles Review of Books, July 3, 2012.

- “Stephen King: You Can Be Popular and Good” by Erik Nelson, Salon, July 6, 2012.

- Just After Sunset: Stories by Stephen King (Scribner, 2008).

- “Harvey’s Dream” by Stephen King, New Yorker, June 20, 2003.

Art Information

- Stephen King © Shane Leonard; press image

- "The Crowd at U-Mass Lowell," "Stephen King Reads," and "Stephen King Answers"

© William Carito; courtesy of Barbara Ross and Maine Crime Writers - "A Conversation with Stephen King" poster @ Wendy Glaas; used by permission

Wendy Glaas is an assistant editor at Talking Writing and clerk of the TW Advisory Board.

Of the King-Dubus event, Wendy says the most “random question” asked came from a woman holding a framed picture. The woman said, “Mr. King, my three favorite things in the world are the Red Sox, Stephen King, and reading. In my hands is a photograph of all three of those things.”

Sure enough, it was a photo of Stephen King at Fenway Park in Boston, reading a book. Her question: “What book were you reading in the picture?” King’s answer: The Friends of Eddie Coyle by George V. Higgins.