Essay by Patricia Dubrava

Out of America, Back in Time—and No Way to Return

On my second visit, I had a cold. Mama María gave me a long look. Breaking an egg into a glass, she grated shavings of something that looked like bone over it. She contemplated the jelly jars that crowded the window ledge above her sink, settled on pinches of dried herbs from three of them, added a splash of water, gave the whole a quick stir, and handed it to me.

“Toma todo de una vez,” she ordered, and no one needed to translate for me. I stared at the lightly beaten yolk, drifting in a slow yellow swirl.

I tried to drink the concoction, wanted to drink it for her, but gagged.

Tony winced, gave me a warm glance, even turned a little green. I would remember that as a rare moment when he showed me tenderness.

Still, it was clear I was on my own. No one contradicted Mama María. She looked dismayed. Maybe she’d never seen such a reaction to one of her cures. I could tell her now that gagging in such circumstances is culturally determined, but neither of us knew that then.

• • •

Soon after Tony and I married, he took me to meet his grandmother for the first time. She lived in La Junta, Colorado, south of Pueblo. We were finishing the dinner she made for us—chile verde with pork, fideo in tomato sauce with onions, tortillas from scratch—when a couple came to the door.

They called her “Doña María,” perched on the edge of the couch, asked how everyone was, and commented on the weather. After some minutes, the man said, “We brought you some fresh eggs.” He handed her a brown grocery bag, its top folded shut.

She thanked him with a crisp nod, as if the gift were expected, set the bag on the table without looking in it. She put some of her herbs into a thick cloth satchel and got her rebozo with its muted blue stripes. Covering her head with it and crossing the ends over her shoulders, she left with the man and his wife.

Tony had said nothing to prepare me for this place, this woman. The year was 1970, the town about 170 miles south of Denver. I stared at the door Doña María had gone through with the couple who’d brought the eggs. I looked at my husband.

“Someone’s sick,” Tony offered impatiently, which didn’t help much.

I was 24, had grown up in Florida towns where blacks and whites lived and went to school separately, and the Cuban invasion hadn’t happened yet. I hadn’t known any religion but Southern Baptist. I’d not yet heard the word curandera. During the less than two years we were married, no one in the family—not even Tony—ever said it. Curandera. Healer.

Mama María came home late that night, after we were asleep on the bed across from hers. In the morning, a rich mix of wood smoke and bacon grease woke us. She had the stove fired up, frying eggs, heating chile and tortillas to fortify us for the three-hour drive north. She said nothing about where she’d been, and we didn’t ask.

• • •

In Denver, where we lived, I’d found that Tony’s relationship with his mother was a minefield. Twice now, our visits to her had ended in heated exchanges and abrupt departures. But when Tony introduced me to Mama María, he beamed. She was his maternal grandmother, his abuelita. Her husband had died fifteen years before, sitting in his pickup at a construction site, his heart attack so swift and lethal that the open thermos of coffee balanced between his legs hadn’t spilled a drop.

My communication with her was mostly in gestures. My high school Spanish was a dim memory, and although I’d seen evidence that she understood English, she didn’t speak it.

My communication with her was mostly in gestures. My high school Spanish was a dim memory, and although I’d seen evidence that she understood English, she didn’t speak it.

Mama María was short and slender, her bearing erect. Her skirt skimmed her ankles, revealing heavy black lace-up shoes. Despite her 75 years and sun-creased face, she’d gone gray only at the temples. “That’s her Indian blood,” I heard various family members say sagely.

Her house was a homemade adobe rectangle, two rooms and a wood-burning stove. Its narrowness reminded me of the trailers I’d spent half my growing years in. The floor was dirt, tamped and smoothed, below layers of straw and newspapers covered with linoleum. Scatter rugs on top of that, sample squares stitched together. The front room contained the black stove that divided the kitchen from the rest. The back room had two beds, hers and another that could be pushed against the opposite wall for guests; the outhouse was a two-seater.

She’d had cold water and electricity the last few years, so now the old well in the front yard was covered with boards weighed down by stones, and kerosene lamps rusted in the shed. Leoncio, her oldest son, had installed the electricity and running water. He’d even bought her an electric iron, but she couldn’t get used to the cord, cut it off and heated the iron on the stove. It was a story the family, now mostly city people, liked to tell, though Mama María dismissed it with a flick of her hand, as if shooing a fly.

There was an altar in the bedroom, covered with a white cloth whose border she’d embroidered in green and red, the colors of the Mexican flag. Her children in Denver didn’t keep the custom, so it was the first home altar I’d seen. The shelf held candles, crosses of various sizes, red and orange paper flowers, and small figurines of saints. They were all foreign to me, except for St. Francis, whom I knew by the bird on his shoulder. A crucifix of dark wood hung above, beside a print of the Virgin of Guadalupe, her green, star-studded robe surrounded by a sunburst of golden light.

A snapshot of Tony and his younger brother Tomás near the altar stopped me the first time I saw it. At about ten and eight years of age, the brothers were shirtless in the bare yard, laughing, their arms flung around each other’s shoulders. I’d never seen them look so happy.

• • •

She lived alone, had no phone or TV, but Mama María never seemed surprised when we arrived. Of course, on my third and last visit, she knew we were coming for Leoncio’s funeral.

Her first-born child hadn’t moved to Denver as Tony’s parents had; instead, Leoncio had raised his family in Rocky Ford, a nearby small town. He didn’t look like her other children, either. Leoncio was darker, more Indian.

María Maldonado had been fifteen when a soldier of the Mexican Revolution raped her—or so she once told me, with Tony translating. Was the soldier a Villista? One of the federales? Did she know which side he was on? That dismissive flick of her hand: It didn’t matter. With a small group, she fled north on foot from Chihuahua, learning she was pregnant along the way. It took weeks, maybe months, to reach the States.

“Seguimos caminando. We just kept walking.” She shrugged. “We didn’t know when we left México.” In 1911, crossing the border had been a more amorphous matter.

Mama María’s yard was dusty or muddy, depending on the weather, and for the funeral in early spring, it had turned to mud. It was my only time with the extended family. I hadn’t met many of them yet and, as it turned out, wouldn’t see most again: six aging children and spouses; their grown children; grandchildren, aunts, uncles, cousins. I was the only güera—the only blonde. I was grateful to be treated courteously, to have people switch to English when they saw me, and to discover that many of the younger people also spoke little or no Spanish.

The afternoon of the rosary, the day before the funeral, my mother-in-law Amalia arrived with her current boyfriend, her daughter (my teenaged sister-in-law), and the two small boys from her second marriage. Mama María was at the stove when they came. Her embrace of her daughter was brief and cold. She never glanced at the boyfriend.

The afternoon of the rosary, the day before the funeral, my mother-in-law Amalia arrived with her current boyfriend, her daughter (my teenaged sister-in-law), and the two small boys from her second marriage. Mama María was at the stove when they came. Her embrace of her daughter was brief and cold. She never glanced at the boyfriend.

Neighbors came with food and offers of places to sleep for the overflow. Amalia had already made arrangements to stay with a cousin, which surprised no one and was a huge relief to me. Spanish bubbled around us. By now, I had begun to catch some words and phrases, but in a blur, like trying to read pages being turned too fast.

The women carried rosaries to pray with us for the sudden death of Leoncio at 58. He’d been awarded the Bronze Star in World War II. A yellowing photo occupied the center of the altar shelf, bracketed by burning votives. Taken during his military days, it showed a young, handsome Leoncio in uniform. The Mexican and American flags crisscrossed behind him; the words “United We Stand” ran in flowing script across his medal-decorated chest.

I never met him. He wasn’t close to his sister Amalia or her children, didn’t visit Denver. Tony said it was because Amalia never liked Leoncio’s wife, a heavyset woman who was sobbing every time we glimpsed her among the neighbors and relatives in Mama María’s crowded house.

That first night, after the rosary, those who stayed with Abuelita slept in the only bedroom. Mama María, with one of her other daughters—Tony’s aunt—and the aunt’s older daughter slept in one bed. I shared the other with the two younger girls. The men, Tony and Tomás and the aunt’s son, took the couch and backseats of the cars.

The next morning, we started getting ready for the funeral mass soon after breakfast. At Mama María’s, life’s basic routines took a long time. A pan of water heated on the wood-burning stove. She poured some into a bowl and handed it to me, smiling, giving me the honor of a first wash.

I smiled back, knowing she liked me as much as I liked her in spite of our language barrier. With everyone waiting, I hurried outside to wash up before getting dressed in a corner of the bedroom. On my previous visits, I’d perfected the art of undressing modestly, putting on my nightgown first before taking my clothes off beneath it. For the funeral, I put on my dress, then pulled off my jeans.

At the church, Amalia and the widow cried loudly, embracing each other.

“Mom will be wherever the drama is,” Tony said drily.

“Leo, Leo, how could you do this to me?” the widow wailed.

Mama María ignored them. She was impassive through the mass, then the burial at a cemetery a few blocks from the church, moving through it all with her straight spine and crisp step. She didn’t cry. She buried her child of the Revolution with American military honors and Mexican Catholic ritual.

I relished the kneeling and rising, the incense and robes, the chanted repetitions of the rosary: Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners now and at the hour of our death. Although I would soon feel differently, then it seemed lyrical, beautifully elaborate, and more pleasing than the plain Baptist church of my childhood, with its “come to Jesus” call at the end of every service.

After the funeral, Amalia couldn’t wait to whisper to me as soon as the widow was out of earshot, relishing every word. Yes, Leoncio died of a heart attack like his stepfather, she hissed, but in his mistress’s bed, a woman no one had known about.

We returned from the cemetery to the modest adobe house, walking across muddy ground a quarter mile after the dirt road ended, our dress shoes caking with rims of clay. The women fixed big pots of frijoles and chile verde—muy picante, very spicy—a stack of tortillas. The neighbors brought more food: enchilada casserole, tamales, bags of chips and cookies. We sat down to eat with water, coffee, and a plastic jug of red Kool-Aid for the kids.

The men chopped wood for the stove. The women heated water, washed dishes, moved mattresses down to the floor so people could sleep. The house had no shade, the bedroom one small window; despite the thick adobe walls, with so many people, the air was sticky.

Different people shared the beds than the night before. Some had driven back to Denver or gone to sleep with other relatives in the area everyone called Barrio Nuevo, the “New Addition,” where the houses were wood-frame, not adobe. The child sleeping next to me tossed and turned for a long time, had a phlegmy cough and clogged breathing. Before I fell asleep, I heard the man on the couch snoring softly. Another sat outside in the dark for awhile, strumming sad ballads on his guitar. Tú, solo tú, eres causa de todo mi llanto.

The baby in the next bed woke crying at 3 a.m., and his mother gave him his bottle, soothed him in soft Spanish, ya, ya, m’ijo,‘stás bien.

By the time of Leoncio’s funeral, I knew “Doña” was a title of respect and that María Maldonado was the neighborhood curandera. Her patients spoke little English, seldom went to doctors. She delivered babies and saw children through fevers. But she never talked about it. Neither did anyone else.

My brother-in-law Tomás would be in prison within the year. My young sister-in-law would be pregnant at sixteen. Tony cycled through bouts of depression during which, for hours at a time, he paced and ranted about dying. One chilled autumn evening in Denver, not long after the funeral, he laid a gun on our kitchen table. I fled from our apartment, running shoeless, coatless, for blocks.

Our marriage would end a few months later. But long after it did, I had the urge to visit La Junta again, to ask Doña María, the woman who had walked, pregnant, from Chihuahua to Colorado, which herbs might help my chronic sinus infections, whether she had a cure for heartache—or if she knew how it had come to this.

Author’s Note

This story happened over forty years ago, and María Maldonado is long dead. My first marriage was short and left me afraid of my ex-husband. I’ve had no contact with him in all that time, though here I’ve changed the names of almost everyone in his family, even if there’s slim chance of his reading it—if he’s still alive. That old fear, faint as it is now, kept me from writing this story for decades.

Going through old files a couple years ago, I came upon two yellowing pages, typed on my old manual typewriter—I recognized the partially filled-in e—describing a visit to La Junta. It was what historians call a primary source document. It reminded me of how richly exotic Doña María’s world had been to me, how much I instinctively fastened onto the one strong, stable member of the family I’d just joined.

Still, finding a way to organize that ancient, rambling description into a satisfactory story eluded me. When at last I developed a plan, it didn’t work very well. I tinkered with it and put it away again, dissatisfied, unwilling to change the structure I’d become attached to. Ah, yes. You must kill your darlings, a thing to be relearned with every new piece of writing. I have two trusted readers, who convinced me to do a major revision, and a good editor who took it the rest of the way it needed to go.

I have remembered that woman, known for such a brief time, so often over the decades. And María Maldonado is her real name. She deserves that, even if no one who knew her ever sees this piece.

Art Information

- "Manos Que Trabajan" © Norberto Chavez-Tapia; Creative Commons license.

- "Filling" © Valerie Hinojosa; Creative Commons license.

- "Ojas" © Valerie Hinojosa; Creative Commons license.

- "Rosarios" © Luis Roberto Lainez; Creative Commons license.

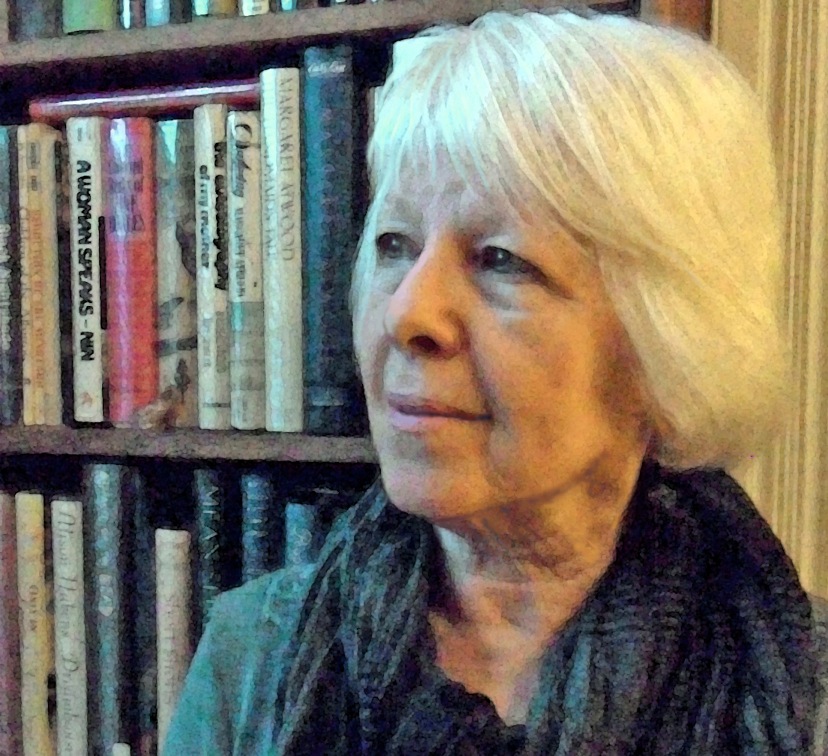

Patricia Dubrava has published two collections of poems and one of stories translated from the Spanish. One of her translations is included in New Border Voices: An Anthology (Texas A&M University Press, 2014), and another is forthcoming in Norton’s international anthology of flash fiction. Her essay on teaching appeared in Hippocampus, Winter 2013. Her “What I Love About Translating,” ran as a guest post on Lisa Carter’s Intralingo blog in April 2014.

Patricia Dubrava has published two collections of poems and one of stories translated from the Spanish. One of her translations is included in New Border Voices: An Anthology (Texas A&M University Press, 2014), and another is forthcoming in Norton’s international anthology of flash fiction. Her essay on teaching appeared in Hippocampus, Winter 2013. Her “What I Love About Translating,” ran as a guest post on Lisa Carter’s Intralingo blog in April 2014.

This is Pat’s second appearance in Talking Writing. Her blog, Holding the Light, is short creative nonfiction, and she’s posted in it two times a month for two years, resulting in almost fifty new pieces of writing.